Wholly Smokes (2 page)

Henry Porteus Kissing the Bride (Pocahontas)

He had staggered off to bed very late in the evening. Either by design or mistake, he had wandered into Rolfe’s cabin – the bridal bower, where the newlyweds lay sleeping. On realizing his mistake, he started to creep away, but the sight of the lovely Pocahontas seemingly changed his mind. Henry removed his coat and flung it over the bride’s head. He then seized her and carried her outside. (The good-natured maiden did not struggle or cry out, supposing it all to be some sort of obscure English joke, like the shivaree.)

When the wedding party caught him, Henry

had already tied Pocahontas over his saddle and was preparing to ride away. Had he done so, it might have led to an international incident between the English settlers and the followers of Chief Powhatan. Fortunately, he paused to light his pipe, so history did not take a bizarre turn.

Henry Badcock

Instead, Henry was expelled from the settlement, and his name expunged from all records. After changing his name to “Henry Badcock,” he made his way into the wilderness, where he hacked out a small clearing and used his meager savings to start a tiny plantation – tobacco, of course.

It was a success from the start. Within a few years, Henry Badcock’s plantation had grown to medium size, making him a moderately wealthy man. He could even afford a wife – literally, since

he paid 180 lb. of tobacco to have his bride shipped from England. The same ship brought him an African slave – the first of many.

The Wonderful Weed:

Nicotiana tabacum

“Oh the miserable and calamitous spectacle!” – John Evelyn

Erasmus Badcock

When Henry Badcock died in 1665, he left a plantation of 11,000 acres and 24 slaves. He was succeeded in the family business by his grandsons, Enoch and Erasmus Badcock. Enoch managed the estate, but young Erasmus had a hankering to see the world, which was becoming a very different place for tobacco. Some praised the wonderful medicinal properties of tobacco, which was said to cure toothache, worms, halitosis, lockjaw, and cancer. Others believed that it caused tremors, staggering, and a withering of

the “noble parts.”

Some countries (Russia, China, Persia) executed people for using tobacco. Others (England and France) encouraged its use and levied enormous taxes upon it. Turkey, which had earlier banned tobacco (and daily executed up to 18 smokers) now legalized the weed as no more dangerous than other everyday drugs: wine, coffee, and opium.

In America, tobacco had become so precious that it was now the official money of Virginia and Maryland. In England, tobacco was now hedged around by a thousand regulations: Englishmen could buy it only from the colonies, which in turn, could sell it only to England. And always in the middle sat the government, levying punishing taxes on every leaf. It rankled young Erasmus to see the labor of his slaves turned into precious tobacco, only to have the Crown and other parasites snatch away the best part of it.

He wondered if there was not some way of cutting out the government and other middlemen. He traveled to England with a shipment of his family’s tobacco.

I thoughte that I shd see for myself how the tobaccoe factors, brokers, diverse merchants, &c. do grow rich from our golden leaves, and how we might ourselves

increase our profitt from trading direct to tobacconists.

When he arrived in London in 1666, the city was still in the clutches of the Great Plague. This worked in Erasmus’s favor, for many customs officials and other watchdogs had fallen ill. Erasmus, an enterprising lad, managed to evade the duty and secretly convey a large consignment of tobacco from the docks to a riverfront warehouse in Thames Street. From there, he took small quantities out to sell to retailers. (By this time, there were some 7,000 tobacconists in London.) Nor did he neglect advertising.

I posted bills on every wall of the citie, informing all and sundry how smoaking is a certain way to ward off the deadly Plague. Those accustomed to the Pipe need have no fear of falling Sick.

By Saturday, September 1, Erasmus had unloaded most of his duty-free stock on the fearful public. He spent that evening drinking at the Star Inn with a new friend, Thomas Farynor, who ran a bakery next door. The two enterprising businessmen became great friends. Erasmus tried to persuade him to carry a line of tobacco in his bakery, but Thomas, who was the King’s baker, had no time for such foolishness. Erasmus

walked him home, where Thomas put out the fire in his oven for the night, then sat down with him for a final pipe. When the baker said good-night and went up to bed, Erasmus sat finishing his pipe and meditating for a moment on the marketing possibilities of selling tobacco in bakeries, butcher shops, indeed, wherever food was sold. Finally he emptied his pipe and strolled back to his lodgings at the Star Inn.

The fire seems to have begun near where Erasmus emptied his pipe. There were rushes on the floor, which must have smoldered for an hour or more, before blazing up to catch the baker’s store of firewood. By 1 a.m., the bakery was a-blaze. Thomas Farynor and his family escaped by clambering along a roof gutter to a neighboring house (all but one servant girl, who perished in the fire).

The sparks from the burning home fell on hay and fodder in the yard of the nearby Star Inn. From there the fire engulfed the Church of St. Margaret. It spread in waves down Pudding Lane and Fish Hill Street to Thames Street, where it found fuel indeed: warehouses full of tallow, oil, brandy and hemp (and the small remainder of Erasmus’s tobacco), open heaps of hay, timber and coal. By 8 a.m., the fire was raging halfway across Old London Bridge.

London was then a city of half-timbered medieval buildings, covered with pitch and thatched

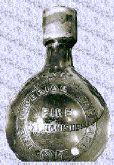

with straw, that flared up at the touch of a spark. A strong wind blew sparks everywhere. There was only the most modest equipment, such as buckets and bottles of water, to combat the blaze.

“Imperial Grenade” or Bottle of Water

to be Thrown at the Fire (1666)

John Evelyn’s journal recorded the panic:

The conflagration was so universal, and the people so astonished, that from the beginning, I know not by what despondency or fate, but crying out and lamentation, running about like distracted creatures without at all attempting to save even their goods; such a strange consternation there was among them, so as it burned both in breadth and length, the churches, public halls, Exchange, hospitals, monuments, and ornaments, leaping after a prodigious manner, from house to

house and street to street…All the sky was of a fiery aspect, like the top of a burning oven, and the light seen above 40 miles round about for many nights. God grant mine eyes may never behold the like…

The Great Fire of London, 1666

The Great Fire of London burned for four days, and was finally stopped only when the Duke of York began blowing up houses with gunpowder, to create a fire-break. By this time, it had destroyed four-fifths of London, over 13,000 houses and 86 churches. Though few lives were lost, the property damage ran to £10 million. For years, debtors’ prisons were filled with those ruined by the Great Fire of London.

Erasmus, fortunately, was able to escape with his gold and even collect the remnant of his tobacco. He began visiting debtors’ prisons, now crowded with those ruined men who had lost their businesses and property. He explained to

them how tobacco could be a great solace and comfort in their time of despair. Sometimes he helped a poor unfortunate by buying up his ruined property at a bargain price. When he sailed back to Virginia, Erasmus was doing very well for himself, very well indeed.

The Badcock clan continued to grow and prosper over the next century. The plantation grew to a phenomenal 340,000 acres, manned by 780 slaves. It was rivaled only by the decidedly second-place plantation of Robert “King” Carter (a mere 300,000 acres and 700 slaves).

One branch of the family moved to Boston where, in 1759, Samuel Badcock opened a small snuff mill. The Virginia Badcocks derided snuff as a foppish fad which would never last. Israel Badcock of Jamestown wrote:

The habit of taking fnuff is no more than an Affectacion of the French, brought back to England by Charles II and fpread throughout his Court. Thofe Boftonians who fancy themselves to be Gentlemen will of courfe haften to take up this Frivolity, but it hath no ftaying power.