Who Says Elephants Can't Dance?: Leading a Great Enterprise through Dramatic Change (19 page)

Read Who Says Elephants Can't Dance?: Leading a Great Enterprise through Dramatic Change Online

Authors: Jr. Louis V. Gerstner

Tags: #Collins Business, #ISBN-13: 9780060523800

But deciding to sell your leading-edge technologies to your own competitors? Imagine having the following conversations: You are talking to IBM’s top technical leaders. They are renowned not only within IBM but throughout their fields. Many have been inducted into the most prestigious scientific and technical academies and bodies. Most have devoted their entire careers to seeing one or maybe two breakthrough innovations come to market inside an IBM

product. Now, explain to them that you plan to sell the fruits of their labors to the very competitors who are trying to kill IBM in the marketplace.

Imagine having the same conversation with a sales force that’s WHO SAYS ELEPHANTS CAN’T DANCE? / 147

clashing daily with the likes of Dell, Sun, HP, or EMC—companies that would likely be the big purchasers of that technology.

You can appreciate the internal controversy surrounding the decision to build a business based on selling our technology components—the so-called merchant market or Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) business. It was just as difficult as deciding to provide services for non-IBM equipment and enabling IBM software to work with competitors’ hardware. And the controversy wasn’t only within IBM.

Now imagine another conversation. This time you are talking to the senior leaders of companies like Dell, HP, and Sun. On the one hand, you’re asking them to buy technology from you, i.e., enter into a business relationship that makes you money—money that you can put into a war chest and use to compete against them in the marketplace.

On the other hand, you’re asking them to trust you to supply them with vital components that they will need for their own products, against which you compete. You promise them that if the supply of those critical parts should ever become tight, they won’t find themselves over a barrel, or in one. It’s easy to understand the emotion and the mutual suspicions surrounding this business.

The announcement in April 1994 that we would mount a serious push to sell our technology on the merchant market was equal parts business pragmatism and another roll of the dice that we could succeed in a business that was just as novel for us as IT services was.

Selling components is a vastly different business than selling finished systems. The competitors and buyers are different. The economics are different. We had to build an organization from the ground up.

But the upside was compelling.

• The IBM Research Division was far more fertile and creative than our ability to commercialize all of its discoveries. We were under-utilizing a tremendous asset.

• Dispersing our technology more broadly would drive our ability to influence the definition of the standards and protocols that underlie the industry’s future development.

• Selling our technology would recoup some of our substantial R&D

expenditures and open up a new income stream.

148 / LOUIS V. GERSTNER, JR.

• In a post-PC world, there would be high demand for components to power all the new digital devices that would be created for network access.

IBM Research

As I said earlier, it has been well known for half a century that IBM has one of the most prolific and important scientific research laboratories in the world. IBM has more Nobel laureates than most countries do, has won every major scientific prize in the world, and has consistently been the foundry from which much of the information technology industry has emerged.

However, the Research Division of the early 1990s was a troubled place. My colleagues there saw the company being broken up into pieces and wondered where a centrally funded research organization would fit in an IBM that was being disaggregated. When they heard I had decided to keep the company together, the collective sigh of relief that emanated from Yorktown Heights, New York (the headquarters of our Research organization) was almost audible.

One of the obvious but puzzling causes of IBM’s decline was an inability to bring its scientific discoveries into the marketplace effectively. The relational database, network hardware, network software, UNIX processors, and more—all were invented in IBM’s laboratories, but they were exploited far more successfully by companies like Oracle, Sun, Seagate, EMC, and Cisco.

During my first year at IBM I probed frequently and deeply into the question of why this transfer of technology invention into market WHO SAYS ELEPHANTS CAN’T DANCE? / 149

place performance had failed so badly. Was it a lack of interest on the part of IBM researchers to deal with customers and commercial products? It did not take long to realize that the answer was no.

The major breakdown was on the product side, where IBM was consistently reluctant to take new discoveries and new technologies and commercialize them. Why? Because during the 1970s and 1980s that meant cannibalizing existing IBM products, especially the mainframe, or working with other industry suppliers to commercialize new technology.

For example, UNIX was the underpinning of most of the relational database applications in the 1980s. IBM developed relational databases, but ours were not made available to the fastest-growing segment of the market. They remained proprietary to IBM systems.

Getting Started

The easiest step we could take initially was to license technology to third parties. This process did not involve selling actual components or pieces of hardware and software, but it did allow other companies access to our patent portfolio or our process technology.

(“Process technology” is, as the name suggests, the technology required for the IT industry’s own manufacturing processes—the skills and know-how to build leading-edge semiconductor and storage components.) This effort—licensing, patent royalties, and the sale of intellectual property—was a huge success for us. Income from this source grew from approximately $500 million in 1994 to $1.5

billion in 2001. If our technology team had been a business unto itself, this level of income would have represented one of the largest and most profitable companies in the industry!

However, this was just the first step to opening the company store.

We moved on from simple licensing to actually selling technol 150 / LOUIS V. GERSTNER, JR.

ogy components to other companies. Initially, we sold fairly standard products that were broadly available in the marketplace but that, nevertheless, IBM chose to make for itself. Here we were competing with many other technology suppliers, such as Motorola, Toshiba, and Korean semiconductor manufacturers. The principal product we offered in the market was simple memory chips called DRAMs (pronounced D-RAMS).

Selling commodity-like technology components is a feast-or-famine business driven not so much by customer demand as by capacity decisions made by the suppliers. Our DRAM business made a gross profit of $300 million in 1995 (the feast), then proceeded to lose $600 million three years later (the famine).

We were not naïve about the nature of this business; its cyclicality was well documented. It turned out, however, that the downturn of 1998 proved to be the worst in the history of the industry.

Why were we in the DRAM business? Well, we really didn’t have any choice. We had to prove to the world that we were serious about selling technology components. Most of the potential customers for our technology were worried (quite appropriately) that they might begin to depend on us and that we would subsequently decide to turn inward again.

Consequently, riding the DRAM wave was the price of admission for us to enter the technology component marketplace. We had essentially exited the DRAM market by 1999, but by then DRAMs had given us an entry point. Now potential customers worried less about our reliability as a supplier or whether we had a serious commitment to this business.

We were ready to tackle the emerging opportunity in the components business: The change in computing that we’ve been talking about was driving a fundamental shift in the strategic high ground in the chip industry.

As I’ve discussed, the action was going to be driven by the proliferation of Internet access devices, exploding data and transaction WHO SAYS ELEPHANTS CAN’T DANCE? / 151

volumes, and the continued build-out of communications infrastructure. All that was driving demand for chips—and, to our great delight, chips that would have fundamentally different characteristics from the lookalike processors that powered lookalike personal computers.

In this new model, value would shift to chips that powered the big, behind-the-scenes processors. At the other end of the spectrum there would be demand for specially designed chips that would go inside millions, if not billions, of access devices and digital appliances. And in between would be chips in the networking and communications gear.

This is the kind of sophisticated development activity that not only allows great technology companies to shine, but it also generates margins that support the underlying investment necessary to lead.

Over the next four years, IBM’s Technology Group went from nowhere to number one in custom-designed microelectronics. I’m happy to say that PowerPC has experienced its own renaissance here, quietly reemerging as a simpler, cheaper, more efficient processor used in a wide range of custom applications, including game consoles. Just consider that IBM’s contracts with Sony and Nintendo in 2001 hold the potential to produce more intelligent devices than the entire PC industry produced in 2000.

As a result—and here’s the important point—IBM, for the first time in its history, is now positioned to benefit from the growth of businesses outside the computer industry. This diversification does not take us away from our core skills; we have simply extended them to entirely new markets.

Our Technology Group is still young and developing. We can’t yet declare victory in this, the third of our growth strategies. It is a piece of unfinished business that I leave for my successor.

Nevertheless, while the economic benefits of our Technology Group strategy have been uneven, the underpinnings of the strategy are powerful and potentially huge for IBM. First, if one believes in the

152 / LOUIS V. GERSTNER, JR.

theory of building great institutions around core competencies and unique strengths, then exploiting IBM’s technological treasure trove is an extraordinary opportunity for the company.

Second, the evidence to date is fairly clear: The two companies that have enjoyed the highest market valuation in the IT industry over much of the last decade have been component manufacturers—Intel and Microsoft. Certainly one derives enormous benefit from its virtually monopolistic position. But there is no doubt that a strategy built around providing fundamental building blocks of the computing infrastructure has proven to be extremely successful in this industry.

B

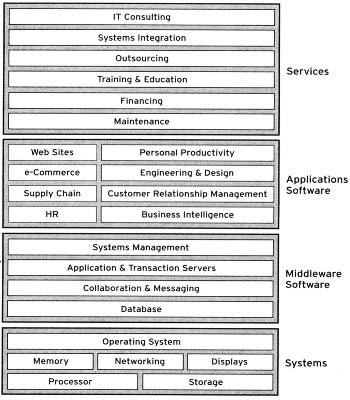

efore you proceed with this chapter, let me make one disclaimer about the upcoming diagram. I am not going to launch into a primer on computing topologies. Instead, I want to use this oversimplified picture of the industry’s structure to illustrate the flip side of our work to restore IBM’s economic viability. This is about the bone-jarringly difficult task of forcing the organization to limit its ambition and focus on markets that made strategic and economic sense.

The diagram is commonly called “the stack,” and people in the computer industry love to talk about it. The stack shows most of the major pieces in a typical computing environment. At the base are components that are assembled into finished hardware products; operating systems, middleware, and software applications sit above the hardware; and it’s all topped off by a whole range of services.

Of course, it isn’t anywhere near as simple as this in real life.

By now you know that IBM’s strategy when it birthed the Sys 154 / LOUIS V. GERSTNER, JR.

tem/360 was to design and make every layer of this stack. But thirty years later the industry model had changed in two fundamental ways. First, very small companies were providing pieces inside the stack that IBM had invented and owned for so long, and customers were purchasing and integrating these pieces themselves.

Second, and just as threatening, two more stacks emerged. One was based on the open UNIX operating platform. The second was based on the closed Intel/Microsoft platform. In the mid 1980s, when IBM had more than a 30 percent share of the industry, the company could safely ignore these offshoots. But by the early 1990s, when IBM’s share position was below 20 percent and still falling fast, it was long past time for a different strategy.

We had to accept the fact that we simply could not be everything to everybody. Other companies would make a very good living inside the IBM stack. More important, just to stay competitive we were going to have to mount massive technical development efforts. We couldn’t afford not to participate in the other stacks, where billions of dollars of opportunity was being created.

I’ve already described the results of our decision to expand into the UNIX and Wintel markets—reinventing our own hardware platforms at the same time that we built new businesses in software, services, and component technologies. Just as important, we had to get serious about where we were going to stake our long-term claims inside the IBM stack.

The first and bloodiest decision was the determination that we would walk away from the OS/2 v. Windows slugfest and build our software business around middleware. Before the 1990s came to a close, we made another strategic withdrawal from a software market.