Who Owns the Future? (18 page)

Read Who Owns the Future? Online

Authors: Jaron Lanier

Tags: #Future Studies, #Social Science, #Computers, #General, #E-Commerce, #Internet, #Business & Economics

How will Kickstarter know whether something is a simulation or rendering [ . . . instead of a photograph of a physical prototype]?

We may not know. We do only a quick review to make sure a project meets our guidelines.

I would like to see Kickstarter grow to be larger than Amazon, since it embodies a more fundamental mechanism of overall economic growth. Instead of just driving prices down, it turns consumers into a priori funders of innovation. But at an Amazon-like scale there would inevitably be an even bigger wave of tricksters, scammers, and the clueless to be dealt with.

Kickstarter continues to produce some wonderful success stories and a huge ocean of doomed or befuddled proposals. Maybe the site will enter into an endless game with scammers and the clueless, as it scales up, and render itself irrelevant. Or it might adopt

crowdsourced voting or automatic filters to keep out crap, only to find that crap is smart and happy to jump through hoops to get through. Or maybe Kickstarter will become more expensive to use, and less naïvely “democratic,” because human editors will block useless proposals. Maybe it will learn to take on at least a little risk to go with the benefits. Whatever happens, success will be dependent on finding some imperfect but survivable compromise.

The Nature of Our Confusion

Successful network ventures that become known to the public are always eventually gamed by epidemics of scammers. Unscrupulous “content farms” turn out drivel and link to themselves in an attempt to climb high on Google’s search results, and bloggers herded by major media companies are encouraged to spice up their writing with key words and phrases not to grab human attention, but the attention of Google’s algorithms.

To Google’s credit, the company has engaged in battle with these encroachments, but the war is never over. When Google measures people, and the result has something to do with who gets rich and powerful, people don’t sit around like flu viruses awaiting impartial assessment. Instead they play the game.

Sites with reviews are stuffed with fake reviews. When education is driven by big data, not only must teachers teach to the test, but it often turns out that there’s widespread cheating.

What is odd, over and over, is that computer scientists and technology entrepreneurs are always shocked at this turn of events. We geeky sorts would prefer that the world passively await our mastery to overtake it, though that is never so.

Our core illusion is that we imagine big data as a substance, like a natural resource waiting to be mined. We use terms like

data-mining

routinely to reinforce that illusion. Indeed some data is like that. Scientific big data, like data about galaxy formation, weather, or flu outbreaks, can be gathered and mined, just like gold, provided you put in the hard work.

But big data about people is different. It doesn’t sit there; it plays

against you. It isn’t like a view through a microscope, but more like a view of a chessboard.

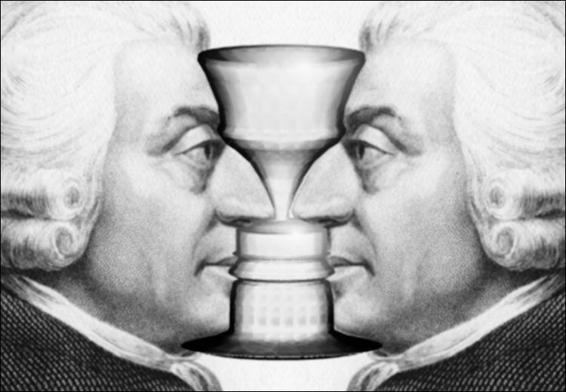

A classic optical illusion might be helpful.

This is the famous figure/ground illusion popularized by Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin in 1915. A contour can be seen equally as a golden goblet or two faces. Neither interpretation is more correct than the other. (In this case I have used Adam Smith’s face.)

In the same way, cloud information generated by people can be perceived either as a valuable resource you might be able to plunder, like a golden vase, or as waves of human behavior, much of it directed against you. From a disinterested abstract perspective, both perceptions are legitimate.

However, if you are an interested participant in a game, it is in your interest to perceive those faces first and foremost.

Here is yet another statement of the core idea of this book, that data concerning people is best thought of as people in disguise, and they’re usually up to something.

The Most Elite Naïveté

Attentive readers will note a continuing rotation in perspectives as I ridicule the illusions of big human data. Sometimes I write as if I were complaining from an everyman’s perspective about being analyzed and treated as a pawn in a big data game. Other times I write as if I were playing a big data game and am annoyed at how my game is being ruined because so many others also play against me.

No one knew how digital networking and economics would interact in advance. Instead of a story of villains, I see a story of technologists and entrepreneurs who were pioneers, challenging us to learn from their results.

My argument is not so much that we should “fight the power,” but that a better way of conceiving information technology would really be better for most people,

including

those ambitious people who plan to accomplish giant feats. So I am arguing

both

from the perspective of a big-time macher

and

from the perspective of a more typical person, because any solution has to be a solution from both perspectives.

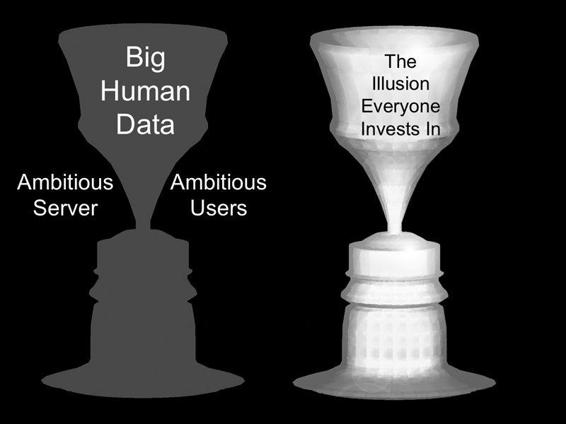

Big human data, that vase-shaped gap, is the arbiter of influence and power in our times. Finance is no longer about the case-by-case judgment of financiers, but about how good they are at locking in the best big-data scientists and technologists into exclusive contracts. Politicians target voters using similar algorithms to those that evaluate people for access to credit or insurance. The list goes on and on.

As technology advances, Siren Servers will be ever more the objects of the struggle for wealth and power, because they are the only links in the chain that will not be commoditized. If present trends continue, you’ll always be able to seek information supremacy, just as old-fashioned barons could struggle for supremacy over land or natural resources. A new energy cycle will someday make oil much less central to geopolitics, but the information system that manages that new kind of energy could easily become an impregnable castle. The illusory golden vase becomes more and more valuable.

THIRD INTERLUDE

Modernity Conceives the Future

MAPPING OUT WHERE THE CONVERSATION CAN GO

An endgame for civilization has been foreseen since Aristotle. As technology reaches heights of efficiency, civilization will have to find a way to resolve a peculiar puzzle: What should the role of “extra” humans be if not everyone is still strictly needed? Do the extra people—the ones whose roles have withered—starve? Or get easy lives? Who decides? How?

The same core questions, stated in a multitude of ways, have elicited only a small number of answers, because only a few are possible.

What will people be when technology becomes much more advanced? With each passing year our abilities to act on our ideas are increased by technological progress. Ideas matter more and more. The ancient conversations about where human purpose is headed continue today, with rising implications.

Suppose that machines eventually gain sufficient functionality that one will be able to say that a lot of people have become extraneous. This might take place in nursing, pharmaceuticals, transportation, manufacturing, or in any other imaginable field of employment.

The right question to then ask isn’t really about what should be done with the people who used to perform the tasks now colonized by machines. By the time one gets to that question, a conceptual mistake has already been made.

Instead, it has to be pointed out that outside of the spell of bad philosophy human obsolescence wouldn’t in fact happen. The data that drives “automation” has to ultimately come from people, in the form of “big data.” Automation can always be understood as elaborate puppetry.

The most crucial quality of our response to very high-functioning machines, artificial intelligences and the like, is how we conceive of the things that the machines can’t do, and whether those tasks are considered real jobs for people or not. We used to imagine that elite engineers would be automation’s only puppeteers. It turns out instead that big data coming from vast numbers of people is needed to make machines appear to be “automated.” Do the puppeteers still get paid once the whole audience has joined their ranks?

NINE DISMAL HUMORS OF FUTURISM, AND A HOPEFUL ONE

Each of ten tropes, which I call “humors,”

*

can be compressed into simple statements about how human identity, changing technology, and the design of civilization fit together. Since technological culture influences what technologists create, and technology is what makes the future different from the past, techie vocabulary is important.

*

Ancient physicians like Hippocrates understood the original humors as a small set of forces or essences that flowed through the human body. They were each a kind of fluid (black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, or blood) but also elements (air, fire, water, earth) and personality type. Black bile corresponded to melancholy, for instance.

I choose to avoid the loaded term

meme

. There are many reasons to avoid

meme

in this case; the primary one being that good ideas are not remotely as plentiful as varieties of traits in natural organisms. You might find this set of “technological humors” to be useful. If so, it is only because the solution space for how a person can react to accelerating technological change is small.

†

†

An admonition: Please, please don’t try to implement my classification scheme of humors in some cloud software startup in order to organize the expressions of other people. They are only offered as thoughts, not as truth. In other words, I hope you find it helpful to consider them analytically, in a personal, skeptical fashion, but not as a way to constrain or determine future events through the structure of software.

No end of ontologies has been proposed to describe the human condition, from the enneagram to the

DSM

. Ontologies can be fun and useful, but of course it’s essential to not take them too seriously. As with all ontological schemes, my humors are not meant to be confused with reality itself.

Each humor is a trefoil binding politics, money, and technology to the human condition:

•

Theocracy:

Politics is the means to supernatural immortality.

This is the oldest and still most common humor, which proposes that the natural world is but a political theater that functions as a remote control of a more significant supernatural world. Politics here serves as the interface to that other world.

*

*

Yes, of course this is not a blanket definition of all religion or spirituality. Also, as I argue all the time, materialism doesn’t even break a sweat to become as crazy and cruel as religion can be at its worst. A Stalin can keep up with any religious inquisition. Yet, there is a global ancient political phenomenon that must be given a name.

Eight of the other humors collected here are naturalistic. A rapture, messiah, or other supernatural discontinuity in the future has not, as a matter of definition, been part of the discussion of the

natural

future until fairly recently, with the advent of the idea of the Singularity. Now we must include old religion in order to put new religion in context.

•

Abundance:

Technology is the means to escape politics and approach material immortality.

Tech will someday become so good that everyone will have everything and there will be no need for politics. “Abundance” is a commanding humor in Silicon Valley, though it was pioneered in ancient Greece. It is both futuristic and ancient.