White Teeth (29 page)

“What's happening now?” asked Clara, rushing back to her seat with a bowl of Jamaican fried dumplings, from which Irie snatched three.

“Same, man,” Millat grumbled. “Same. Same. Same. Dancing on the wall, smashing it with a hammer. Whatever. I wanna see what else is on, yeah?”

Alsana snatched the remote control and squeezed in between Clara and Archie. “Don't you dare, mister.”

“It's

educational,

” said Clara deliberately, her pad and paper on the armrest, waiting to leap into action at the suggestion of anything edifying. “It's the kind of thing we all should be watching.”

Alsana nodded and waited for two awkward-shaped bhajis to go down the gullet. “That's what I try and tell the boy. Big business. Tip-top historic occasion. When your own little Iqbals tug at your trousers and ask you where you were whenâ”

“I'll say I was bored shitless watching it on TV.”

Millat got a thwack round the head for “shitless” and another one for the impertinence of the sentiment. Irie, looking strangely like the crowd on top of the wall in her everyday garb of CND badges, graffiti-covered trousers, and beaded hair, shook her head in saddened disbelief. She was that

age.

Whatever she said burst like genius into centuries of silence. Whatever she touched was the first stroke of its kind. Whatever she believed was not formed by faith but carved from certainty. Whatever she thought was the first time such a thought had ever been thunk.

“That's

totally

your problem, Mill. No interest in the outside world. I think this is

amazing.

They're all free! After all this time, don't you think that's

amazing

? That after years under the dark cloud of Eastern communism they're coming into the light of Western democracy, united,” she said, quoting

Newsnight

faithfully. “I just think democracy is man's

greatest

invention.”

Alsana, who felt personally that Clara's child was becoming impossibly pompous these days, held up the head of a Jamaican fried fish in protest. “No, dearie. Don't make that mistake. Potato peeler is man's greatest invention. That or Poop-a-Scoop.”

“What they want,” said Millat, “is to stop pissing around wid dis hammer business and jus' get some Semtex and blow de djam ting up, if they don't like it, you get me? Be quicker, innit?”

“Why do you talk like that?” snapped Irie, devouring a dumpling. “That's not your voice. You sound ridiculous!”

“And you want to watch dem dumplings,” said Millat, patting his belly. “Big ain't beautiful.”

“Oh, get lost.”

“You know,” murmured Archie, munching on a chicken wing, “I'm not so sure that it's such a good thing. I mean, you've got to remember, me and Samad,

we were there.

And believe me, there's a good reason to have it split in two. Divide and conquer, young lady.”

“Jesus

Christ,

Dad. What are you

on

?”

“He's not on anything,” said Samad severely. “You younger people forget why certain things were done, you forget their significance. We were there. Not all of us think fondly upon a united Germany. They were different times, young lady.”

“What's wrong with a load of people making some noise about their freedom? Look at them. Look at how

happy

they are.”

Samad looked at the happy people dancing on the wall and felt contempt and something more irritating underneath it that could have been jealousy.

“It is not that I disagree with rebellious acts

per se.

It is simply that if you are to throw over an old order, you must be sure that you can offer something of substance to replace it; that is what Germany needs to understand. As an example, take my great-grandfather, Mangal Pandeâ”

Irie sighed the most eloquent sigh that had ever been sighed. “I'd rather not, if it's all the same.”

“Irie!” said Clara, because she felt she should.

Irie huffed. And puffed.

“Well! He goes on like he knows everything. Everything's always about

himâ

and

I'm

trying to talk about now,

today,

Germany. I bet you,” she said, turning to Samad, “I know more about it than you do. Go on. Try me. I've been studying it all term. Oh, and by the way: you

weren't

there. You and Dad left in 1945. They didn't do the wall until

1961

.”

“Cold War,” said Samad sourly, ignoring her. “They don't talk about hot war anymore. The kind where men get killed. That's where I learned about Europe. It cannot be found in books.”

“Oi-oi,” said Archie, trying to diffuse a row. “You do know

Last of the Summer Wine

's on in ten minutes? BBC Two.”

“Go on,” persisted Irie, kneeling up and turning around to face Samad. “Try me.”

“The gulf between books and experience,” intoned Samad solemnly, “is a lonely ocean.”

“Right. You two talk such a load of shâ”

But Clara was too quick with a slap round the ear. “Irie!”

Irie sat back down, not so much defeated as exasperated, and turned up the TV volume.

Â

The twenty-eight-mile-long scarâthe ugliest symbol of a divided world, East and Westâhas no meaning anymore. Few people, including this reporter, thought to see it happen in their lifetimes, but last night, at the stroke of midnight, thousands lingering both sides of the wall gave a great roar and began to pour through checkpoints and to climb up and over it.

Â

“Foolishness. Massive immigration problem to follow,” said Samad to the television, dipping a dumpling into some ketchup. “You just can't let a million people into a rich country. Recipe for disaster.”

“And who does he think he is? Mr. Churchill-gee?” Alsana laughed scornfully. “Original whitecliffsdover piesnmash jellyeels royalvariety britishbulldog, heh?”

“Scar,” said Clara, noting it down. “That's the right word, isn't it?”

“Jesus

Christ.

Can't any of you understand the enormity of what's going on here? These are the last days of a regime. Political apocalypse, meltdown. It's an historic occasion.”

“So everyone keeps saying,” said Archie, scouring the

TV Times.

“But what about

The Krypton Factor,

ITV? That's always good, eh? 'Son now.”

“And stop sayin' âan historic,' ” said Millat, irritated at all the poncey political talk. “Why can't you just say â

a,

' like everybody else, man? Why d'you always have to be so la-di-da?”

“Oh, for fuck's sake!” (She loved him, but he was

impossible.

) “What possible fucking difference can it make?”

Samad rose out of his seat. “Irie! This is my house and you are still a guest. I won't have that language in it!”

“Fine! I'll take it to the streets with the rest of the proletariat.”

“That girl,” tutted Alsana as her front door slammed. “Swallowed an encyclopedia and a gutter at the same time.”

Millat sucked his teeth at his mother. “Don't

you

start, man. What's wrong with â

a

' encyclopedia? Why's everyone in this house always puttin' on fuckin' airs?”

Samad pointed to the door. “OK, mister. You don't speak to your mother like that. You out too.”

“I don't think,” said Clara quietly, after Millat had stormed up to his room, “that we should discourage the kids from having an opinion. It's good that they're free-thinkers.”

Samad sneered, “And you would know . . . what? You do a great deal of free-thinking? In the house all day, watching the television?”

“Ex

cuse

me?”

“With respect: the world is complex, Clara. If there's one thing these children need to understand it is that one needs

rules

to survive it, not

fancy.

”

“He's right, you know,” said Archie earnestly, ashing a fag in an empty curry bowl. “Emotional mattersâthen yes, that's your departmentâ”

“Ohâwomen's work!” squealed Alsana, through a mouth full of curry. “Thank you

so much,

Archibald.”

Archie struggled to continue. “But you can't beat experience, can you? I mean, you two, you're young women still, in a way. Whereas

we,

I mean, we are, like,

wells of experience

the children can use, you know, when they feel the need. We're like encyclopedias. You just can't offer them what we can. In all fairness.”

Alsana put her palm on Archie's forehead and stroked it lightly. “You

fool.

Don't you know you're left behind like carriage and horses, like candlewax? Don't you know to them you're old and smelly like yesterday's fishnchip paper? I'll be agreeing with your daughter on one matter of importance.” Alsana stood up, following Clara, who had left at this final insult and marched tearfully into the kitchen. “You two gentlemen talk a great deal of the youknowwhat.”

Left alone, Archie and Samad acknowledged the desertion of both families by a mutual rolling of eyes, wry smiles. They sat quietly for a moment, while Archie's thumb flicked adeptly through

An Historic Occasion, A Costume Drama Set in Jersey, Two Men Trying to Build a Raft in Thirty Seconds, A Studio Debate on Abortion,

and back once more to

An Historic Occasion.

Click.

Click.

Click.

Click.

Click.

“Home? Pub? O'Connell's?”

Archie was about to reach into his pocket for a shiny ten pence when he realized there was no need.

“O'Connell's?” said Archie.

“O'Connell's?” said Samad.

CHAPTER TEN

The Root Canals of Mangal Pande

Finally,

O'Connell's.

Inevitably,

O'Connell's. Simply because you could be without family in O'Connell's, without possessions or status, without past glory or future hopeâyou could walk through that door with nothing and be exactly the same as everybody else in there. It could be 1989 outside, or 1999, or 2009, and you could still be sitting at the counter in the V

-

neck you wore to your wedding in 1975, 1945, 1935. Nothing changes here, things are only retold, remembered. That's why old men love it.

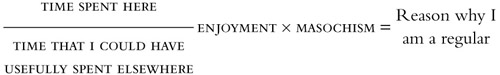

It's all about time. Not just its stillness but the pure, brazen amount of it. Quantity rather than Quality. This is hard to explain. If only there was some equation . . . something like:

Â

Something to rationalize, to explain, why one would keep returning, like Freud's grandson with his

fort-da

game, to the same miserable scenario. But

time

is what it comes down to. After you've spent a certain amount, invested so much of it in one place, your credit rating booms and you feel like breaking the chronological bank. You feel like staying in the place until it pays you back all the time you gave itâeven if it never will.

And with the time spent, comes the knowledge, comes the history. It was at O'Connell's that Samad had suggested Archie's remarriage, 1974. Underneath table six in a pool of his own vomit, Archie celebrated the birth of Irie, 1975. There is a stain on the corner of the pinball machine where Samad first spilled civilian blood, with a hefty right hook to a racist drunk, 1980. Archie was downstairs the night he watched his fiftieth birthday float up through fathoms of whiskey to meet him like an old shipwreck, 1977. And this is where they both came, New Year's Eve, 1989 (neither the Iqbal nor Jones families having expressed a desire to enter the nineties in their company), happy to take advantage of Mickey's special New Year fry-up: £2.85 for three eggs, beans, two rounds of toast, mushrooms, and a generous slice of seasonal turkey.

The seasonal turkey was a bonus. For Archie and Samad, it was really all about being the witness, being the

expert.

They came here because they

knew

this place. They knew it inside and out. And if you can't explain to your kid why glass will shatter at certain impacts but not others, if you can't understand how a balance can be struck between democratic secularism and religious belief within the same state, or you can't recall the circumstances in which Germany was divided, then it feels goodâno, it feels

greatâ

to know at least one particular place, one particular period, from firsthand experience, eyewitness reports; to be the authority, to have time on your side, for once,

for once.

No better historians, no better experts in the

world

than Archie and Samad when it came to

The Postwar Reconstruction and Growth of O'Connell's Poolroom.

Â

1952

Ali (Mickey's father) and his three brothers arrive at Dover with thirty old pounds and their father's gold pocket-watch. All suffer from disfiguring skin condition.

1954â1963

Marriages; odd-jobs of all varieties; births of Abdul-Mickey, the five other Abduls, and their cousins.

1968

After working for three years as delivery boys in a Yugoslavian dry-cleaning outfit, Ali and his brothers have a small lump sum with which they set up a cab service called Ali's Cab Service.

1971

Cab venture a great success. But Ali is dissatisfied. He decides what he really wants to do is “serve food, make people happy, have some face-to-face conversations once in a while.” He buys the disused Irish poolroom next to the defunct railway station on the Finchley Road and sets about renovating it.

1972

In the Finchley Road only Irish establishments do any real business. So despite his Middle Eastern background and the fact that he is opening a café and not a poolroom, Ali decides to keep the original Irish name. He paints all the fittings orange and green, hangs pictures of racehorses, and registers his business name as “Andrew O'Connell Yusuf.” Out of respect, his brothers encourage him to hang fragments of the Qur n on the wall, so that the hybrid business will be “kindly looked upon.”

n on the wall, so that the hybrid business will be “kindly looked upon.”

May

13, 1973

O'Connell's opens for business.

November

2, 1974

Samad and Archie stumble upon O'Connell's on their way home and pop in for a fry-up.

1975

Ali decides to carpet the walls to limit food stains.

May

1977

Samad wins fifteen bob on fruit machine.

1979

Ali has a fatal heart attack due to cholesterol build-up around the heart. Ali's remaining family decide his death is a result of the unholy consumption of pork products. Pig is banned from the menu.

1980

Momentous year. Abdul-Mickey takes over O'Connell's. Institutes underground gambling room to make up for the money lost on sausages. Two large pool tables are used: the “Death” table and the “Life” table. All those who want to play for money play on the “Death” table. All those who object for religious reasons or because out of pocket play on the friendly “Life” table. Scheme a great success. Samad and Archie play on the “Death” table.

December

1980

Archie gets highest ever recorded score on pinball: 51,998 points.

1981

Archie finds unwanted cut-out of Viv Richards on Selfridges shop floor and brings it to O'Connell's. Samad asks to have his great-grandfather Mangal Pande's picture on the wall. Mickey refuses, claiming his “eyes are too close together.”

1982

Samad stops playing on the “Death” table for religious reasons. Samad continues to petition for the picture's installation.

October

31, 1984

Archie wins £268.72 on the “Death” table. Buys beautiful new set of Pirelli tires for clapped-out car.

New Year's Eve, 1989, 10:30

P.M

.

Samad finally persuades Mickey to hang portrait. Mickey still thinks it “puts people off their food.”

Â

“I still think it puts people off their food. And on New Year's Eve. I'm sorry, mate. No offense meant. 'Course my opinion's not the fucking word of God, as it were, but it's still my opinion.”

Mickey attached a wire round the back of the cheap frame, gave the dusty glass a quick wipe-down with his apron, and reluctantly placed the portrait on its hook above the oven.

“I mean, he's so bloody

nasty-

looking. That mustache. He looks like a right

nasty

piece of work. And what's that earring about? He's not a queer, is he?”

“No, no, no. It wasn't unusual, then, for men to wear jewelry.”

Mickey was dubious, giving Samad the look he gave to people who claimed to have got no game of pinball for their 50p and came seeking a refund. He got out from behind the counter and took a look at the picture from this new angle. “What d'you think, Arch?”

“Good,” said Archie solidly. “I think:

good.

”

“Please. I would consider it a great personal favor if you would allow it to stay.”

Mickey tilted his head to one side and then the other. “As I said, I don't mean no offense or nothing, I just think he looks a bit bloody

shady.

Haven't you got another picture of him or sommink?”

“That is the only one that survives. I would consider it a great personal favor, very great.”

“Well . . .” ruminated Mickey, flipping an egg over, “you being a regular, as it were, and you going on about it so bloody much, I suppose we'll have to keep it. How about a public survey? What d'you think, Denzel? Clarence?”

Denzel and Clarence were sitting in the corner as ever, their only concession to New Year's Eve a few pieces of mangy tinsel hanging off Denzel's trilby and a feathered kazoo sharing mouth space with Clarence's cigar.

“Wass dat?”

“I said, what d'you think of this bloke Samad wants up? It's his grand-father.”

“

Great-

grandfather,” corrected Samad.

“You kyan see me playing dominoes? You tryin' to deprive an ol' man of his pleasure? What picture?” Denzel grudgingly turned to look at it. “Dat? Hmph! I don't like it. He look like one of Satan's crew!”

“He a relative of you?” squeaked Clarence to Samad in his woman's voice. “Dat explain much, my friend, much! He got some face like a donkey's pum-pum.”

Denzel and Clarence exploded into their dirty laughter. “Nuff to put my belly off its digesting, true sur!”

“There you are!” exclaimed Mickey, victorious, turning back to Samad. “Puts the clientele off their foodâthat's what I said right off.”

“Assure me you are not going to listen to those two.”

“I don't know . . .” Mickey twisted and turned in front of his cooking; hard thought always enlisted the involuntary help of his body. “I respect you and that, and you was mates with my dad, butâno disrespect or nuffin'âyou're getting a bit fucking long in the tooth, Samad mate, some of the younger customers might notâ”

“

What

younger customers?” demanded Samad, gesturing to Clarence and Denzel.

“Yeah, point taken . . . but the customer is always right, if you get my drift.”

Samad was genuinely hurt. “

I

am a customer.

I

am a customer. I have been coming to your establishment for fifteen years, Mickey. A very long time in any man's estimation.”

“Yeah, but it's the majority wot counts, innit? On most other fings I defer, as it were, to your opinion. The lads call you âThe Professor' and, fair dues, it's not without cause. I am a respecter of your judgment, six days out of every seven. But bottom line is: if you're one captain and the rest of the crew wants a bloody mutiny, well . . . you're fucked, aren't you?”

Mickey sympathetically demonstrated the wisdom of this in his frying pan, showing how twelve mushrooms could force one mushroom over the edge and onto the floor.

With the cackles of Denzel and Clarence still echoing in his ears, a current of anger worked its way through Samad and rose to his throat before he was able to stop it.

“Give it to me!” He reached over the counter to where Mangal Pande was hanging at a melancholy angle above the stove. “I should never have asked . . . it would be a dishonor, it would cast into

ignominy

the memory of Mangal Pande to have him placed here in thisâthis irreligious house of shame!”

“You what?”

“Give it to me!”

“Now look . . . wait a minuteâ”

Mickey and Archie reached out to stop him, but Samad, distressed and full of the humiliations of the decade, kept struggling to overcome Mickey's strong blocking presence. They tussled for a bit, but then Samad's body went limp and, covered in a light film of sweat, he surrendered.

“Look, Samad,” and here Mickey touched Samad's shoulders with such affection that Samad thought he might weep. “I didn't realize it was such a bloody big deal for you. Let's start again. We'll leave the picture up for a week and see how it goes, right?”

“Thank you, my friend.” Samad pulled out a handkerchief and drew it over his forehead. “It is appreciated. It is appreciated.”

Mickey gave him a conciliatory pat between the shoulder blades. “Fuck knows, I've heard enough about him over the years. We might as well 'ave him up on the bloody wall. It's all the same to me, I suppose. Comme-see-comme-sar, as the Frogs say. I mean, bloody

hell.

Blood-ee

-hell.

And that extra turkey requires hard cash, Archibald, my good man. The golden days of Luncheon Vouchers are over. Dear oh dear, what a

palaver

over nuffin' . . .”