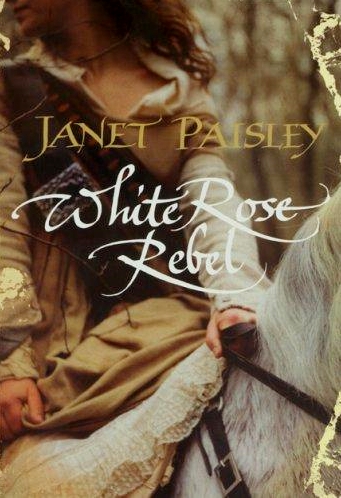

White Rose Rebel

WHITE ROSE REBEL

‘A feisty heroine, romantic dash, battle scenes of eye-watering gore’

Financial Times

‘Not just a stirring tale of Highland passion and adventure, this is

also an expertly plotted, psychologically insightful narrative from

one of Scotland’s most exciting literary minds’ Kevin MacNeil,

author of

The Stornoway Way

‘A hot-blooded riposte to the Highland machismo of clan history’

Sunday Herald

‘Will make your heart soar and your Saltire swing’

Daily Record

‘The inspirational story of Scotland’s warrior queen’

Herald

‘In the warrior woman of the Jacobite cause, ‘Colonel Anne’

Farquharson-Mackintosh, Janet Paisley has found a feisty,

feminist heroine for today.

White Rose Rebel

is more than a tartan

bodice-ripper – it dramatizes the anguish, loyalty, treachery and

brutality of civil war, before affirming the unquenchable

power of love and freedom’ Dorothy McMillan

‘A swashbuckling adventure’

Gloss

‘Pacey, racy… a hot little kilt-lifter’

Sunday Times

‘Paisley is first-rate – she has reinvented the form and made it

her own… She writes with a confidence that is informed by several

factors – her obviously deep love for Scotland, her tenacity in espousing

the liberty of the individual and her determination to ensure the

presence of women in Scotland’s history… Her creation of

Anne Farquharson is a triumph’

Scottish Review of Books

Janet Paisley’s oeuvre includes five poetry collections, two of short fiction, a novella and numerous plays, radio, TV and film scripts. Accolades include a prestigious Creative Scotland Award (

Not for Glory

, stories), the Peggy Ramsay Memorial Award (

Refuge

, a play) and a BAFTA nomination (

Long Haul

, a short film). Her poetry and short stories have been translated into seven languages and are widely anthologized.

White Rose Rebel

is her first novel.

FICTION

Wicked!

Not For Glory

Wild Fire

POETRY

Ye Cannae Win

Reading the Bones

Alien Crop

Biting through Skins

Pegasus in Flight

VIDEO

Images

FILM

Long Haul

PLAYS

Refuge

Straitjackets

Winding String

Deep Rising

Curds & Cream (Radio 4)

and co-authored with Graham McKenzie

Sooans Nicht

For Want of a Nail

Bill & Koo (Radio 4)

J

ANET PAISLEY

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London

WC2R 0RL

, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London

WC2R 0RL

, England

First published by Viking 2007

Published in Penguin Books 2008

1

Copyright © Janet Paisley, 2007

All rights reserved

Grateful acknowledgement is made for permission to reproduce the following extracts:

True Stories

copyright © Margaret Atwood, 1981, reproduced with permission of Curtis

Brown Group Ltd; ‘The Little White Rose’ from Hugh MacDiarmid’s

Complete Poems

,

reproduced with permission of Carcanet Press Ltd.

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

978-0-14-191056-7

For Sarah and Melanie, guid-dochters, with love

‘There was a singular race of old Scotch ladies. They were a delightful set – strong-headed, warm-hearted, and high-spirited – merry even in solitude; very resolute; indifferent about the modes and habits of the modern world, and adhering to their own ways, so as to stand out like primitive rocks above ordinary society. Their prominent qualities of sense, humour, affection, and spirit, were embodied in curious outsides, for they all dressed, and spoke, and did exactly as they chose.’

Lord Cockburn, 1779

–

1854

Thanks to the Scottish Arts Council for financial support, to Judy Moir for sound editorial advice, to Rennie McOwan, Joan McNaught and Pamela Fraser for research books, to Lucy Conan and Johanna Hall at BBC Radio for the experience in dramatizing history, to Kevin MacNeil for essential assistance with Gaelic, and to Eirwen Nicholson for checks on historical accuracy

.

Don’t ask for the true story;

why do you need it?

It’s not what I set out with

or what I carry.

What I’m sailing with,

a knife, blue fire,

luck, a few good words

that still work, and the tide.

Margaret Atwood

I want for my part

only the little white rose of Scotland

that smells sharp and sweet – and breaks the heart.

Hugh MacDiarmid

In the distance there was a drum beating and the faint skirl of slow pipes. It was a call to the clans, for a chief was dying. At such a time even bitter enemies forgot their grudges, laid their swords aside and set off to honour the call. Undisturbed by the distant beat, a roe deer grazed in the fading light of dusk among heather and rock on the foothills of the Cairngorms. A shot cracked off, then another, with barely a heartbeat between. The deer staggered, fell.

‘

Trobhad!

Come on!’ Calling out in Gaelic, a young girl, maybe twelve or thirteen years old, dashed from the thicket of nearby trees, her grubby face alert with joy as she ran barefoot towards the wounded beast, the musket in her hand still smoking. Her long dark hair was crazily tangled but her dress, though clearly Highland, was velvet and lace.

‘Anne,

fuirich

! Wait!’ An older youth in a chief’s bonnet and kilted plaid emerged behind the girl, the second gun in his hand, the gleam of his red-gold hair still discernible in the gathering dark.

Anne did not heed or hesitate. She dropped the musket as she ran, drew a dirk from the belt at her waist and, to avoid its hooves, leapt over the injured deer, short sword poised. As she leapt, the terrified animal thrashed, trying to rise. Its flailing hooves smacked against her shin. Anne yelped, stumbling on to the heather. The youth, two steps behind, threw down his gun, drew his dirk, fell to his knees and yanked the deer’s head back to finish it. Anne lunged forwards on to its chest to plunge her blade first into the animal’s throat.

‘I got him,’ she said. There was challenge in her voice. The lad glanced at her across the shuddering carcass as the earthy stench of blood rose between them. ‘All right, MacGillivray,’ she conceded. ‘We both got him.’ Then she thrust her fingers into the slowing spurt from the deer’s neck and, with the middle one, drew a bloodied line down the centre of her forehead. ‘But it’s my kill.’

Satisfied that her right was secured, she jumped to her feet. Pain twisted up through her body. The yelp was out before she could stop it. As she staggered, the young MacGillivray caught hold of her. Anne raised her long velvet skirt and looked down. Her right ankle had begun to swell. She tried again to put her weight on it, biting her lip so as not to squeal again with pain.

‘I’ll carry you,’ MacGillivray offered.

‘And what about the deer?’

‘It’ll have to wait.’

‘

Gu dearbh, fhèin, chan fhuirich!

Indeed it won’t!’ She would not lose the kill. There were few deer left on the hills, and they’d been lucky to find this one. Hungry folk were not the only hunters. ‘The wolves would have it before we were half-way home.’

‘I’ll put it in a tree.’

‘You’ll take it back to Invercauld. People won’t arrive to an empty larder now.’

‘They’ll bring food, if they can. It’s been a thin year for all of us.’

‘But he will eat.’ Her throat constricted. ‘And get strength from it.’ Her voice wavered. ‘Maybe then they can all go home again.’

MacGillivray stared down at her. At nineteen, he was a full head taller. He could remind her that the dying chief couldn’t eat, hadn’t for days. Instead, he caught her round the waist, lifted and slung her over his shoulder.

‘What are you doing?’ She struggled.

‘Putting you in the tree,’ he said as he strode back to the thicket.

While she shimmied her backside into the fork of the tree he put her in, MacGillivray primed and loaded her musket before handing it up.

‘But I still think it should be the deer.’

‘Will you go, Alexander?’

He slung his own musket to lie across his chest and swung the deer carcass across his shoulders. He was not happy at the prospect of returning without her. They were not his clan. These were not his lands.

‘MacGillivray,’ she called as he set off. He turned, still ready to hoist the deer into the tree and her out of it. ‘That way,’ she pointed. ‘Follow the drum.’

MacGillivray let his breath out, turned and headed the way she directed. The limp head of the deer banged against his back with every stride, blood still dripping.

‘Tell them I shot it,’ she yelled as he vanished out of sight.

Now she was alone. Among the rocks, two courting wildcats circled each other, yowling. A hunting owl hooted. The moon rose above the hills. Its light made the pool of deer blood gleam in the dark. From the valley beyond, a wolf bayed. Anne shifted in the tree. If the pack came this way, they’d pick up the blood-scent and be after it. MacGillivray had slung his musket first. To load it, he’d have to drop the deer. The wolves would dart in. They would be ravenous, their natural caution blunted. He’d get one shot in, and time to load and fire again as they dragged the deer away but, with only a dirk to use then, if there were more than two wolves, the kill could be lost. Anne looked around the tree, hung her musket on a short branch and drew the dirk from her belt.

By the time the moon reached eleven o’clock in the sky, the wolves had found the congealed puddle of blood. They could smell the sour stink of humans too, but hunger removes much reticence and the ribs of these three animals were visible through their scraggy pelts. One sniffed around the puddle. Another raised its head and yowled. The third picked up the trail of what to them was wounded prey and they all loped off, following it. The fork in the tree where Anne had been was empty. Near it, a jagged branch bore the pale white wood of a fresh cut.

Dribbles of deer blood shone on the rough track made by MacGillivray. Breathing hard, Anne hobbled across rock and heather, a crutch hacked from the tree under her left arm, the butt of her musket under the right, her swollen ankle roughly bandaged by cloth torn from her skirt. She had gone some way towards Invercauld but not enough. From behind her, further back on the trail, a wolf howled. She stopped, half-turned, listened, trying to gauge how far, how fast. The heather-clad ground and low trees were cut

against dark shadows deepened by the high moon. The front of Anne’s dress shone darkly in its light.