White Mischief (27 page)

Authors: James Fox

JC said she heard D and E talking and laughing—but they were not laughing but quarrelling—therefore she:

1. Didn’t hear them.

2. They pretended they were laughing, not quarrelling.

3. They really were laughing. Wilks was wrong.

DB simply heard voices. Probably JC wished to hide the quarrel, it was still one of the better nights.

“There was a door open when D and E came back” (presumably from D’s statement). He also had his veranda key—so he could have got out noiselessly by this door, perhaps returned by it.

Why did Wilks (or the others) not mention D bringing the dog back? Wilks especially.

JC’s evidence covers up for DB, Wilks and Diana

Wilks’s evidence covers up for JC

DB’s evidence implicates no one else

Diana only made a statement

A door was left open. Anyone could have got in or out of it.

What do we know of Wilks anyway?

She says Mrs. C’s chauffeur/butler left—for where? in what? did he come round the next morning?

One of the most interesting items in the Wilks interview was her description of the arrival of Diana and Erroll—the expression on her face “like thunder.” It supported a popular rumour—a story believed by Diana’s own

friends to this day—that she and Erroll had had a terminal row on the night of the murder, after the dinner party. The theory, which varies little from version to version, is based on the idea that Broughton, while pretending to “cut his losses” and behave with scrupulous honour, had in fact reneged on the marriage pact and the promise to pay Diana £5,000 a year.

Broughton almost admitted as much in court, but he turned it round: Diana’s integrity, he said, would have prevented her from claiming the money, and thus the financial part of the pact was effectively waived. Erroll told Diana at the last moment that without finance, the marriage plans were off and Broughton had therefore forced Erroll into officially taking over Diana, knowing that it would be impossible for him to do so. As a result Erroll had lost his nerve and backed away. Broughton was almost broke by this time. In any event he would certainly have been unwilling to finance Diana’s affair with Erroll for three years, or until they could get a divorce. Diana herself was about to lose everything: miles away from home; a baronet, an earl; not one, but two sets of pearls, and above all, her romantic happiness.

Reading some of Broughton’s testimony in this light gives it a new flavour. Here he is explaining his “dispassionate business discussion” with Erroll, within earshot of June and Diana and in view of Erroll’s houseboy and garden boy, who described Broughton beating the table with his fist:

I think on that occasion I enquired about his financial position and Lord Erroll was rather evasive. I could not get out of him what his resources were. [It was surely common knowledge in Nairobi that Erroll was penniless.] I think he said he had not got very much.

I wanted to get out of him

[my italics] exactly what he was worth and I gathered it was not very much. I think he said on that occasion he was afraid Diana would not have all the things she had been used to, or a lot of the things she had been used to.

In 1979 a close friend of Diana’s told me that she had once said to her, quite courageously, “I always thought you shot Joss.” “And she took it quite seriously,” said the friend, “and very well, and said, insisted, that she hadn’t. And I gave her my reasons, which were: he had made it clear to her that in no way could he marry her because, for one thing, she couldn’t be divorced for three years and he had absolutely no money—the reverse: he was very badly in debt. And he more or less said the best thing you can do is go back to Broughton and call it a day. And in her rage she shot him. I said I thought this was quite a feasible thing. And she swore she didn’t.”

Broughton seemed always to be hinting after the murder that something had gone wrong between Joss and Diana. One could perhaps read too much into the following courtroom exchange, taken from Broughton’s testimony, but it might also be read in the light of a letter Broughton wrote after his acquittal to a friend in England, in which he said, “Diana has been completely disillusioned about Erroll by revelations which have come out since all this trouble started.”

In court he was asked by Morris:

You had some hope of everything coming all right in about three months’ time when you returned from Ceylon?

A: | Girls do change their minds. |

Q: | And had you ever heard of Erroll changing his mind? |

A: | Unless I am very much pressed I would rather not answer. |

Q: | I merely suggest to you that you had a double chance of everything being all right in three months? |

A: | Yes. |

Q: | You also knew Lord Erroll’s reputation with regard to that sort of thing, that he was fickle in such matters? |

A: | If I am pressed to answer, yes. |

If there had been an argument between Joss and Diana, why should it have occurred suddenly after the dinner, at which everything seemed to be so amicably settled?

There was no explanation for this and no hard evidence

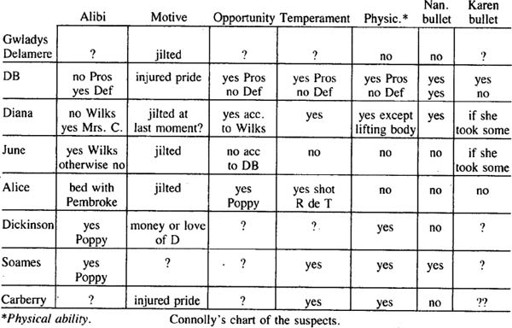

to support the “row” theory, until Connolly stumbled on a witness whose story provided not only a plausible reason for the argument, but also seemed to explain the “missing hour” in the timetable of the movements of Broughton and June Carberry that night.

Lady Barwick, formerly Valerie Ward, who supported Connolly at the Press Council on the question of Gwladys Delamere and the anonymous letters, told Connolly that on the night of the murder June Carberry had invited her to dinner at the Muthaiga Club to celebrate Broughton’s surrender. She and her South African friend, Laurie Wilmot, were dining elsewhere, so June asked them to come on to the Claremont Road House afterwards and join the party. Lady Barwick and her escort had drinks at the Club, at around 7:45. Connolly’s note of his conversation with Lady Barwick tells the rest of the story:

She saw, and spoke to the following: Derek Fisher from Nanyuki, somebody Gaskell. who had an ulcer and drank milk, and Denzil Myers. June and Alice de Trafford were there; Long John Llewellin and his wife, Gypsy someone, Jacko Heath, still alive (1969) and married to Sally Billiard Leake!

After their own dinner she and LW go to Claremont in his camouflaged army car. They were first and were sat down at a long table. Had two dances. Then Diana and Erroll arrived, looking rather unhappy and sat at the end of the table—and later June Carberry and Broughton appeared! Their appearance caused consternation to Joss and D and they were obviously not meant to come. DB looked very white, started protesting immediately. They ignored everyone else. Immediately a terrific row started with DB shouting at Erroll and June booming away, trying to soothe them. It go so bad that she and LW got up and left and went to another club. Blue Room or 400 (up steps). She rather thinks there was someone else at their table. The row was fundamentally a scene of jealousy. Broughton and June then went back to Muthaiga—or where?

Next morning she was rung up because her Buick was the only one in Kenya besides Gibbs and the No. was almost the same (T 7341). [The Registration number of Erroll’s Buick was T 7331.]

Poppy, who usually resisted the suggestion of gaps in his investigations, believed that Valerie Ward’s story may have been correct; was impressed by the missing hour in the timetable, and he confirmed that the police did enquire about other Buicks, in case of confusion over the sightings of Erroll’s car before the murder.

Broughton certainly planned to go to the Claremont Road House that night. He told Mrs. Barkas, Lizzie Lezard and Llewellin how much he was looking forward to it. Lezard understood that Jock would be taking June there as a dancing partner. June never specifically denied going to the Claremont. She simply said, in her evidence, “Joss and Diana went off to the Claremont. Jock asked me if I would like to dance and I said I did not want to, as I was not feeling particularly well.” She supported that by the requests for quinine later on.

Diana and Erroll dancing together at the Claremont Road House had set off Broughton’s rage on another evening, if the prosecution’s information is correct, when he was heard to say to Diana before she left, “Shall I throw the champagne in your face, or break the bottle over his head, or would you rather I threw the bottle at your head?” On this final evening, had their departure again triggered off his anger, so carefully suppressed at dinner under the studied passivity and almost perverse generosity of the toast and the good wishes?

Why did no one else witness Broughton’s scene at the Claremont Road House? Nobody was asked about it, and according to Poppy, Wilks was the only one among the witnesses who volunteered information. Lady Barwick’s version of the last dealings between Broughton and Erroll before the murder, as reported here by Connolly, is close to the popular version:

Valerie Barwick. Part of her theory (obviously based on real knowledge): When it came to the crunch, DB said that he was not going to give her up without a test—he would say that he was not going to give her any money, after all, that if E’s

sentiments were genuine, he would say, “never mind, we’ll manage somehow.” If he didn’t then they would fix him between themselves or some such expression. All this was tried on the last evening and E said something to the effect that he had only made love to her for her money and that without the money there could be no marriage—this could have happened at the club, the night club, the house afterwards, or on the way back to Karen (Wilks’s description of Diana’s anger). Perhaps the scene at the Claremont was the showdown and the moment when DB made up his mind to kill Erroll (though she thinks he had planned the murder for ages).

Reconstructing the scene from this new evidence, Connolly wrote:

The dinner was rather short—8:30 to 10:30 and ended in a

vin triste

. perhaps a quarrel after the Toast … D and E perhaps slipped away suddenly. E is surprised to see DB and JC at Claremont and there is consternation—Diana too. The row flares up and DB

threatens

Erroll. (VW and partner leave.) DB and JC return to Club and he starts off again “It’s all very well June” etc. It is this

threat

he is so frightened of coming out, that he rushes up to Nyeri after the verdict of murder and asks her what she has told the police. She reassures him—only that he was in bad mood at Club. If he made this threat, D would

know

of murder as soon as death of E is established. Hence, can’t abide DB.

The fact that no one gave away the visit of J and DB to the Claremont or the row there suggests that they

all

decided not to mention it. Purpose of DB’s actions: to draw the enemy fire. He asks about prison conditions, fate of man who kills his wife’s lover in flag, delicto—draws attention to bonfire.

If DB had hired a killer he would need an alibi and would therefore ensure Wilks being in and out of his room too—he might also make his presence known to D and E—but he behaved quite differently.

15

LETTERS FROM THE WANJOHI

Loneliness fixed Alice. Everyone was frightened of her.

B

ERYL

M

ARKHAM

Alice de Trafford’s marriage to Raymond had ended long before their divorce in 1938, and she was often alone in her house at Wanjohi, with her Ridgeback dogs and her pet eland. She had fallen in love, after Erroll’s death, with Dickie Pembroke, her alibi for the murder night. Pembroke could never return Alice’s affection with the same intensity, and she began to cling to him with suicidal devotion.

As she took up with Pembroke, so her affair with Lezard came raggedly to an end. It was a period of confusion for Alice. Patricia Bowles remembers that shortly before Diana’s arrival in Kenya, while Erroll was conducting his affair with Mrs. Wirewater, Alice had talked about the possibility of getting Erroll back as her lover.

On the morning after the murder, Alice had begged Lezard urgently to take her to the mortuary to bid farewell to Erroll’s body. They took along Gwladys, and Bewes recorded their arrival in his notebook. What he didn’t record, but what Lezard saw, was that before Alice put the branch of a small tree on Erroll’s body, she kissed him on the lips, pulled the sheet back, smeared it with her vaginal juices and said, “Now you’re mine for ever.”

After that Lezard suspected Alice—the murder fitted in with her morbid preoccupations. And there is a suggestion that she may have confessed to him. In later years Lezard was untypically evasive on the subject. Yet the writer Alastair Forbes, Lezard’s flatmate in London after the war, is convinced that Lezard would have told him if this was the case, “Or if he had either done it himself,” wrote Forbes, “or taken money to do it, or had it done without doing it, his most likely course in the circumstances.”