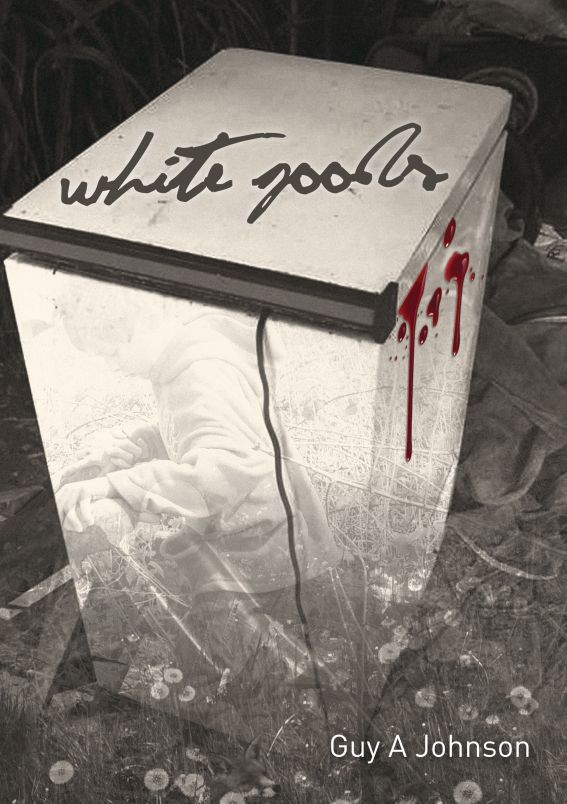

White Goods

Authors: Guy Johnson

White goods

White

goods

by

guy a

johnson

Ending.

On the day that I finally

understood the truth of things, I took the boy by the hand and made

him face it with me.

It’s strange the places

where you find it, the truth. People like to say that it’s staring

you in the face, or that it’s right under your nose. I’ve never

found it in either place, though. And on this day, it wasn’t

obvious – it wasn’t going to leap out at you, not unless you knew

where to look. Luckily, I had quite a good idea. I’m not sure if I

found it, or whether it found me. But we got there, the boy and

me.

All the way, he kept

asking me questions. Where were we going? What time would we be

back? Could we go back now? Wouldn’t people be worried? What was

this all about? Was this an adventure?

I liked the last question.

Made what we were doing sound fun, so I went along with

it.

‘

An adventure,

yes,’ I confirmed.

Our journey together

started at the crematorium, where we laid low for a bit. Waiting

for night to come, so we could move about undetected. All part of

this great adventure, I reassured him. Then, under the cover of a

navy summer’s night, we got on with our quest.

From the crematorium, we

crossed the road and headed towards the dump. From there, we went

past old Crinky Crunkle’s fat, short bungalow, along Church Lane,

across the green next to the Tankards’ place, past the Chequers

public house, turning right into the alleyway that led to the new

housing estate, through that and then onto my road – Victoria

Avenue – with its multi-coloured terraced rows. All the way, the

boy was at my side, keeping up with my hearty pace. He glanced back

a few times, as if looking for a way out, or keeping note of the

route we had taken, but I kept him on track with a few instructions

– ‘Keep up,’ ‘Left here,’ ‘Straight over.’ I said little else, but

it wasn’t needed. He had stopped asking questions and was just

doing as instructed.

It was only when we

finally reached my house that he stalled.

‘

We’re using

the back entrance,’ I instructed in a near-whisper, waiting for him

to move again. To get to our garden via the back, there was an

alleyway between two houses that you had to pass through. Then, you

turned right, went through our immediate neighbours’ garden, before

you reached a gate into ours. It was a weird set up and it always

felt like we were trespassing, even though we weren’t.

‘

Go on,’ I

pressed, giving his arm a gentle tug, but he was still

apprehensive. ‘Nothing to be afraid of,’ I reassured him; it made

little difference, so I changed tack. ‘After this, it’ll be over,

okay? All over.’

‘

Do you

promise?’ he asked, echoing my quiet tone.

‘

I promise,’ I

hushed.

With that, he nodded in

compliance and we finished the last steps of our excursion: through

the alleyway, across next-door’s garden and into ours. We headed

for the wooden shed at the very end; to the place where I was

certain the truth was hiding.

There was a key to the

shed I’d kept under a stone. I retrieved it, slid it into the

padlock on the door and we were in. I shut the door.

‘

In there,’ I

told him, pointing to the back. There, shrouded by a pile of old,

musty blankets was a huge, rusting chest freezer. I threw off the

blankets, opened its mighty, white mouth. The grey seal smacked

apart like a set of thick lips and released a big icy breath into

the air. I still had a hold of his hand, so I pulled him forward,

and pushed that hand into the icy well, where he felt the cold,

harsh reality that lurked inside.

‘

The truth,’ I

announced, not letting go, aware he was now trembling, the terror

eventually manifesting in a wet patch at the front of his

trousers.

I couldn’t tell you

exactly what decided my next move. I couldn’t tell you how I

managed it, either. Physically, or mentally. Hours later - once I’d

thought it through, thought about what I had done - it was too

late. It had happened.

‘

What you

doing?’ the boy managed, defenceless with shock, as I hauled his

little body up, shoving him sharp, tipping him over the edge of the

freezer.

Then the lid was down and

the lock on the handle clicked into place.

1.

There has always been a bit of dispute

over exactly who or what finished our mother off. Different

accounts and stories, with pins of doubt and ambiguity tacked on

along the way.

Ian and Della, my elder siblings, reckoned it was

inevitable. The way she had acted,

what

she did; all

that led up to what eventually happened.

Something-like-that-was-bound-to-happen-sooner-or-later,

was the gist of it.

Dad didn't say much himself, kept it

all hidden inside. Kept very silent on the matter, like it was a

secret.

Auntie Stella, Mum's sister, was more

vocal on the matter: she blamed Electrolux for the whole episode,

particularly when she'd been drinking. Mum wouldn't have liked

that; she didn't have time for drinkers.

'Nothing

worse than a bad drunk,' she used to warn us all, lighting up a

Superking and pointing the red glow of its end at Dad's silver tray

of spirit bottles on the front room sideboard, indicating him.

Which we found odd, because he was quite good at being

drunk.

Mum smoking; the smell of it filling

the lounge. That wasn’t something I thought I’d miss, but I

did.

Losing Mum changed everything. When she

left our lives, there was a gap. And gaps need filling, don’t they?

So, I started looking. Looking in between the gaps, looking for

what should have been there; and finding what was there too,

finding what was supposed to be long dead and deeply

buried.

But that was later and my story starts before then. It

starts with an ending: with

her

ending, on the

day white goods conspired to do-in our beloved mother in her own

house, with her horrified family watching. And a bit before that,

too; on our last holiday together as a family.

You see, I have two beginnings. Two

places where my story can start. And it's hard to know which one

should come first, so I'll have to tell them both at

once.

Our house was number 45, Victoria

Avenue. End of a terrace.

‘

Semi-detached,’ Mum optimistically corrected, should anyone

use that other, less well-to-do phrase.

Number 45. A small front porch led into

the hardly-ever-used front room, with an autumn-yellow carpet,

patterned with leaves. Our best three-piece-suite sat in this room:

bottle green velvet, with wooden arms – dark and glossy. A teak

sideboard squeezed into the right hand alcove. Dad’s stereo was in

here, with his speakers in each corner and his box of LPs from the

sixties. And white boxes – this was where Dad kept most of his

white boxes.

‘

They’ll be gone in a day or so,’ he’d promise Mum, whenever

she complained about them

taking-over-her-whole-house.

And, true to his word, they usually were – only to be

swiftly replaced by another shipment.

A door from

the front room led to a staircase that cut straight across the

house, with just a square of carpet separating you from the door to

the back room. We played for hours on the stairs as kids. We’d shut

the doors at the bottom and at the bedroom doors upstairs and

pretend it was a different place. We would set up a garage of cars

on the L-shaped landing and send the little vehicles flying down

the stairs. I sent my Action-Man tank down them once and it hit

Mum’s legs as she walked through.

‘

You can stop that

right

now! Little

buggers!’

The back room was the room we used the most. Originally,

this had been the kitchen space, before we had

the extension

– I’ll come to that in a bit. Later, it became our family

room: a squeezed-in place, with too much furniture and not enough

space.

‘

You wanna knock through,’

my Auntie Stella was fond of suggesting, like she knew about these

things. ‘Put a spiral staircase in the corner. Open it up. Oh, I’d

love one of them.’

But we never did. We never did anything to our house that

we didn’t really need to. It was privately rented; that was Dad’s

excuse. No point in putting in the effort when it wasn’t ours to

keep. It was a point of pride – the privately rented bit. It

wasn’t

council

was my Dad’s point. It set us apart:

we lived

privately.

In a space

ten feet square, my parents managed to cram a foldaway dining

table, a sofa, an armchair, a TV set and a grey and red leather

pouffe. There was also a door that led to the

cupboard-under-the-stairs; another favourite play-place. The

cupboard housed five foldaway orange-vinyl stools (used to

accompany our dining table), heaps of coats and usually a large

sack or two of potatoes. The floor of the back room was covered in

beige carpet tiles and these in turn had a kaleidoscopic, circular

rug over the top of it - a design of multi-coloured and

multi-patterned triangles, circumferenced in a fringe of red

tassels.

Beyond this was the

extension

– a phrase

that sat proudly alongside

privately-rented

and

semi-detached.

Here

was our kitchen: long, narrow, with limited space and unlimited

appliances. On the left, we had a tall larder, fridge, a gas

cooker, and two doors that hid the airing cupboard and emersion

heater; on the right were the washing machine, dishwasher, and the

sink, with a gas-heater above it that got you instant hot

water.

‘

You a got a dishwasher?’ said my mate Justin, amazed. I

just shrugged, playing it cool. ‘Where’d you get it?’

‘

Comes from Dontask,’ I

said. ‘Haven’t you got one too?’

I wasn’t

supposed to say where our stuff came from – that was one of Dad’s

golden rules. But it didn’t matter with Justin. Our dads worked

together, so it was likely Justin knew anyway.

‘

Where?’ he asked, as if

he’d never heard of it.

‘

You know -

Dontask

.’

Justin

had just

shrugged, like he didn’t really understand, so we changed the

subject.

At the end of the kitchen was the world’s coldest bathroom,

with another door leading off to the world’s coldest toilet. The

flooring throughout the extension was an ornate pattern of red and

black vinyl that

didn’t-show-the-dirt;

the walls differed – pale green in the kitchen, garish pink

in the bathroom, and toilet-flush-blue in the loo.

There was a lean-to just outside the back door, which led

to our garden and the big shed at the end. The lean-to – a roof of

corrugated plastic – was where Dad kept the rest of his white

boxes, the ones that wouldn’t fit in our front

room

.

White boxes full of thingy-me-bobs and

what-ya-ma-call-its. White boxes I wasn’t allowed to go poking in.

Things from Dontask.

Our house, then, where the five of us lived: Mum, Dad, Ian,

Della and me. Until

that

day. Then it was

just the four of us.

When it happened, Ian was upstairs doing

something-he-shouldn’t’ve,

according to Della. He was 16 to my

just-12, but I knew what she was talking about. I’d spied a strange

ritual occurring a few times at night, when it was lights-out

time.

We shared a room, much to his

discontent, and, through the shadows, I’d seen Ian bend his legs up

under the bedclothes, making a small tent. This was accompanied by

a low panting sound and some hand shuffling. It all started off

slow and quiet, but built up in pace and volume, eventually ending

with a sharp gasp – somewhere between joy and being winded –

followed by a slow, satisfied sigh. Then, he’d roll over and go to

sleep.

I’d witnessed this several times before asking Ian about

it. He simply went red in the face and mumbled something

about

finding-out-about-it-all-myself-one-day.

I didn’t ask him again, and the

nightly huff-puffing-shuffling seemed to stop.