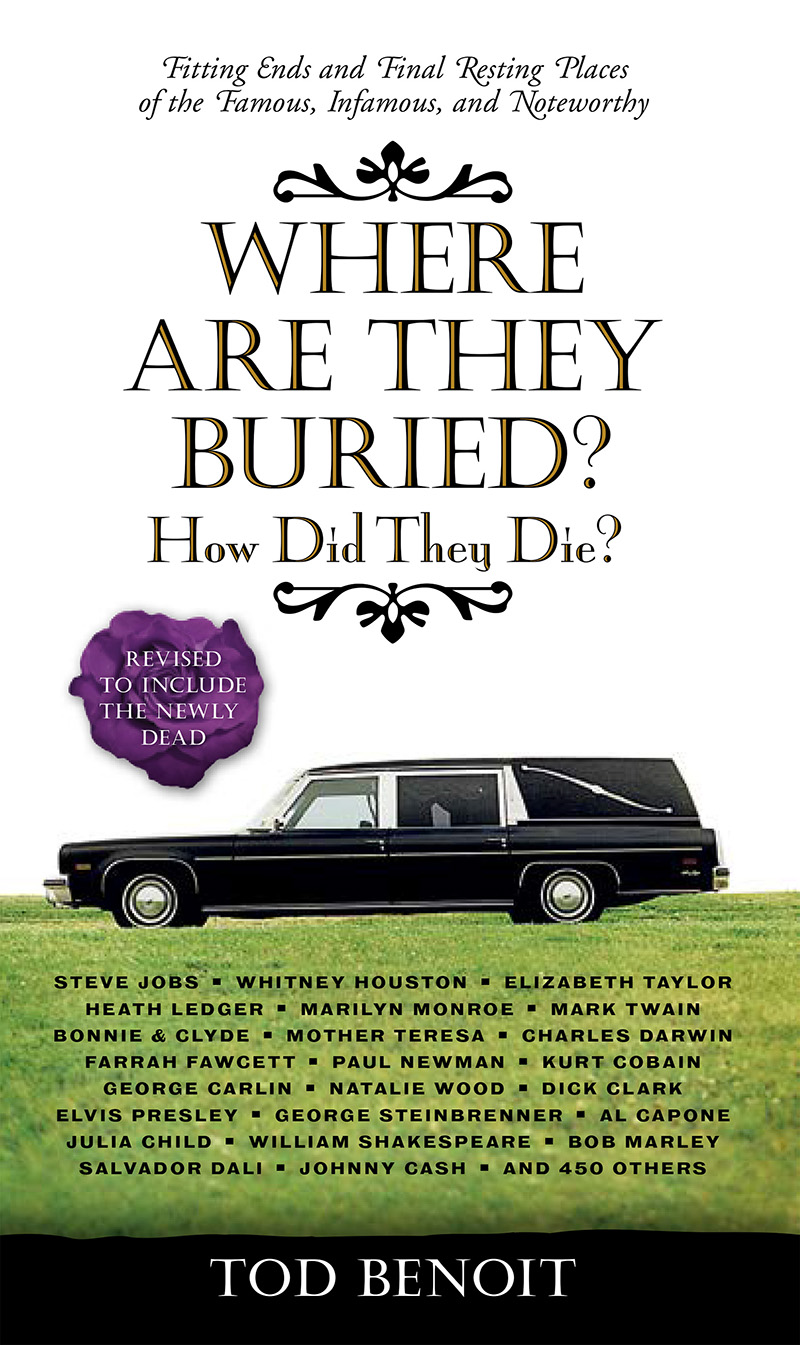

Where Are They Buried?

Read Where Are They Buried? Online

Authors: Tod Benoit

Fitting Ends and Final Resting Places of the Famous, Infamous, and Noteworthy

WHERE ARE THEY BURIED?

How Did They Die?

REVISED & UPDATED

TOD BENOIT

This book is dedicated to the memory of Don Schellhammer, Sr., who died in November 2001 after a lengthy illness. At 58, Don was buried at St. Anne’s Cemetery in Sturbridge, Massachusetts.

For their invaluable contributions, the author is sincerely grateful to the following folks: Brian Benoit for joining in the epic Seattle-to-San Diego run of 1996; Meryl Brodsky for her labors as research librarian extraordinaire; Becky Koh for all of her generosities, including introducing my work to Black Dog & Leventhal; Laura Ross and Lisa Tenaglia, the discerning editors whose unflagging enthusiasm provided light at the end of the tunnel; Sid Roberts for mountaintop lodging; Art Dol for accommodations Down Under; and Chris Shepherd for his enthusiastic and tireless shilling of the finished product.

I’m also indebted to J.P. Leventhal and the staff and freelancers of Black Dog & Leventhal, including Cindy LaBreacht, Kylie Foxx, Michael Driscoll, Sara Cameron, Dara Lazar, Gregory Hurcomb, and True Sims. Their combined efforts have lent a quality to this work that I never could have envisioned.

Finally, kudos to the all of the nameless hundreds of people, from town clerks and funeral home directors to cemetery staff and priests, who’ve gone well out of their way to help this cause.

Television & Film Personalities

Greats of Literature, Philosophy & the Arts

Famous Personalities & Infamous Newsmakers

APPENDIX:

How to Find Where Someone Is Buried

Tomorrow is the most important thing in life.

Comes into us at midnight very clean.

It’s perfect when it arrives and it puts itself in our hands.

It hopes we’ve learned something from yesterday.

—JOHN WAYNE’S EPITAPH

As I recall, the seasonably cool morning of December 9, 1980, became bitterly cold, for me anyway, right around ten o’clock. I think that’s when all this started, more or less.

I took my seat in an English class, nothing new there, and when the bell rang moments later, Chris Lozier bounced to her place directly in front of me. She was bright and cheerful, and in those days her arrival was a highlight.

“Can you believe that about John Lennon?” she asked.

“What, did he make a disco record or something?”

“No, he’s dead. Someone shot him last night.”

And so it was. The quick flash of a gun had claimed another victim. John Lennon hadn’t been the first popular figure to pass on, and he wouldn’t be the last, but the senselessness of his death, and the starkness of its brutality against the kindhearted way of his life, struck a particularly heartfelt chord. While a generation that had been raised to a Beatles soundtrack contemplated its own mortality, the world mourned. At school a few months later we were treated to a rendition of Lennon’s “Imagine” by a most unlikely singer, a fellow student named John Wood. He sang it during an assembly and when he finished, the student body clapped reverentially. Though the pall of Lennon’s death lingered, the pieces were picked up and everyone got over it. There was nothing else to be done.

During the mid-1980s, I attended university in Lowell, Massahusetts, swallowing whole the indoctrinations of the town’s famous literary son, Jack Kerouac, an exhilarating drunk whose ruminating mind tended toward the exploration of society’s underbelly. In an untimely fashion in 1969, Jack drank himself to death, and the buzz in some circles was that he was buried in a nearby cemetery. As friends and I had frequented his old barroom haunts, a pilgrimage to his grave seemed fitting.

The visit proved to be more complicated than I had anticipated. There are numerous cemeteries in Lowell and nobody seemed to know in which one Jack was buried. I finally learned the name of the cemetery by tracking down his obituary, but then had to figure out how to get there. Upon arriving, my plan was again confounded: The office was closed, there was no directory, and Jack’s grave could be anywhere among the thousands of stones. After wandering the cemetery’s rows for a few hours I gave up the search, but returned a few weeks later with John Macolini, a college roommate and fellow Kerouac devotee. Together we eventually located Jack’s grave, but I knew there had to be an easier way to find such landmarks.

The locations of famous graves, and especially the puzzle of exactly how to find them, appealed to me as a kind of offbeat treasure hunt, but responsibilities beckoned and I put the matter on the back burner. Then, in 1992, the death of Sam Kinison, a sublimely deranged comedian, prompted me to pursue a quirky mental exercise: I began to compile a list of the famous deceased who mattered to me, or who might matter to someone else. Personalities like Babe Ruth and James Dean came to mind quickly and, once the most obvious individuals had been collected, I ferreted out additional notable folks from library reference sources. “Year in Review” issues of magazines were especially useful, and they yielded many more obscure or unconventional famous people, such as Dian Fossey, Jim Fixx, and Oskar Schindler. After compiling a list of several hundred famous deceased, I was the proud owner of an apparently worthless pile of information. Filing it away, I moved on.

But in 1994, I chanced upon a newspaper article concerning John Lennon’s slaying. Across the street from the Dakota apartment building in New York City where he was shot, a section of Central Park had been dedicated to his memory and named “Strawberry Fields.” More than a dozen years after John’s death, a steady stream of visitors continued to arrive there in order to commune with John’s spirit, their captivation showing no sign of abating. The article was a concise digest of this curious phenomenon, though, at its most fundamental level, the reporter didn’t quite understand it. But I did.

Humans are unique in the cognizance of their own mortality. Though some may cling optimistically to the concept of a joyous hereafter, most acknowledge our granular contribution to the infinite beach of time and, by default, concede that the ultimate substance of our individual lives is largely irrelevant. But while we accept that all things must pass and nobody lives forever, we still strive to achieve a singularity, a legacy by which we might be remembered. This very human desire to “live on” is affirmed by the importance and elaborateness of our cemeteries, our penchant for visiting and caring for them, and the universally accepted notion of “respect for the dead.” Every tombstone, a kind of waypoint between life and death, confirms individuality. “I was somebody,” they seem to say.

Some 6,700 “somebodies” die in the United States every day, their passing mourned by survivors who keep the flame of their memory burning until joining them in ashes and dust. Though most passings are recognized by relatively small circles of family and friends, some deaths are more publicly mourned because, for better or worse, these people made a lasting imprint on the fabric of our society’s culture. That culture includes all of us, and when John Lennon, or any famous or infamous person, is raised in memory, it’s for the purpose of acknowledging and celebrating his or her unique and lasting stamp on our lives.