When the War Was Over (59 page)

Read When the War Was Over Online

Authors: Elizabeth Becker

The seriousness of this historical revision hit the party like an ax when Pol Pot and Duch added the contention that Vietnam was threatening the country. Duch had produced Tuol Sleng confessions showing that Vietnam had created a parallel underground party in Cambodia years before to sabotage the revolution and eventually hand over the country to Hanoi. Anyone familiar

with Duch's scrupulous paranoia could guess where the next leap in logic would lead. When the party leaders, including men like So Phim, cooperated in the first purge of the Cambodian communist Veterans returned from Hanoi during the war in 1974, they had accepted the party's rationalization that these Veterans were conscious saboteur agents of the Vietnamese communists. When the party later purged the bourgeoisie in 1975 and 1976, the leaders had accepted the party line that the bourgeoisie were agents of the CIA or the KGB implanted years earlier to disrupt the revolution.

with Duch's scrupulous paranoia could guess where the next leap in logic would lead. When the party leaders, including men like So Phim, cooperated in the first purge of the Cambodian communist Veterans returned from Hanoi during the war in 1974, they had accepted the party's rationalization that these Veterans were conscious saboteur agents of the Vietnamese communists. When the party later purged the bourgeoisie in 1975 and 1976, the leaders had accepted the party line that the bourgeoisie were agents of the CIA or the KGB implanted years earlier to disrupt the revolution.

It should have been no surprise that Duch now linked Veteran ICP members to a Vietnamese plot to destroy the revolution. There was enough “evidence” in the dispute between Cambodia and Vietnam to convince Pol Pot that this was the case. The Vietnamese in Hanoi had made it clear to enough “observers” that they would not be displeased if Pol Pot disappeared. They were pressing the Cambodians to sign a special treaty of friendship that would give Vietnam dominance over communist Indochina. Hanoi was refusing to honor the border agreement North Vietnam and the southern PRG had reached with Sihanouk. Moreover, the Khmer Rouge needed the threat of a Vietnamese invasion to distract the population from their own failures.

The party leaders were so caught up within the sudden turns in the regime's policies they could not see how this new stage would lead to their own demise. So Phim did not question the seriousness of this newly revealed Vietnamese threat but he eventually differed with Pol Pot about the best way to defend against it, and this helped seal his fate. All soon discovered there was no choice but to agree with Pol Pot or die. Pol Pot and his intimates saw no question marks. It was a matter of life or death between Cambodia and Vietnam. And in that struggle, Cambodia could only survive if Pol Pot triumphed. Pol Pot ensured that his and the country's fates were intertwined.

The change in the Center's attitude toward Vietnam had been too sudden for some leaders. It had moved from cautious neighborliness to the threat of war in a matter of months. As late as July 1976, when they signed the agreement to allow flights between their two capitals, Cambodia and Vietnam had appeared as if they could live side by side. That fall Ieng Sary spoke up for allowing Vietnam membership in the United Nations at a speech he gave before the UN General Assembly. The decision to change the party birth date and cut off the roots to the ICP had not altered his perception of Cambodia's foreign policy: neutrality, solidarity with the communists and the third world, and identification of the United States and U.S. imperialism as the main enemy.

Even Ieng Sary claims he did not believe the border dispute would lead to war. Though he accepted on blind faith that there were Vietnamese agents planted in the uppermost levels of the party, he says he did not see how this would lead to war between the two countries. “We had let the Vietnamese come [to set up their embassy] before the Chinese. We let the Vietnamese travel where they requested. They traveled by car from Saigon to Phnom Penh and made some trips inside Kampuchea. . . . I never wished for war between Vietnam and Kampuchea. . . . The fear for me was a coup on the inside, not the threat of an invasion from the outside. . . . I said the main problem was internal, because of Vietnamese agents on the inside.”

But this new perception of a life-or-death threat from Vietnam increased Ieng Sary's role as foreign minister. Now Pol Pot was willing to open up the country to foreign visitors and reveal that the Cambodian Communist Party was running Democratic Kampuchea and he was the ruler. Through most of 1977 and 1978 Sary laid the groundwork with China, North Korea, and other nations to introduce Democratic Kampuchea's case to world opinion and win international sympathy in a crusade against Vietnam.

In the first part of 1977, with plans well under way for the purge of the Northwestern Zone, Pol Pot and Duch stepped up their search for the recently uncovered system of “Vietnamese agents” and the preparations for the border war.

So Phim's territory included those stretches of villages bordering Vietnam's Tay Ninh province that were claimed by both Vietnam and Cambodia. When the Center asked him to deploy his troops, So Phim responded immediately, if not enthusiastically, according to some of his surviving colleagues. In March 1977, he ordered the Eastern Zone troops to halt their work in the fields and irrigation sites and move immediately to the border. Phim was directly in charge of defending Highway Seven, the road that runs parallel to the border from the Snuol rubber plantation in the north, past the Memot rubber plantation down to Krek, the heart of the disrupted territory, and then cuts back into Cambodia and crosses the Mekong River at Kompong Cham city.

Highway Seven is the roadway guarding the northern section of what is known as the west bank of the Mekong River. Phim and his Eastern Zone troops had fought ferociously during the war with Lon Nol to retain control of the west bank; Lon Nol's soldiers, for their part, had fought hard to win back the area. Highway Seven ends at the crossroad with Highway Six, the

area of Lon Nol's disastrous operations of Chenla I and Chenla II. At the start of Cambodia's border war with Vietnam, Phim was trusted with one of the most crucial lines of defense.

area of Lon Nol's disastrous operations of Chenla I and Chenla II. At the start of Cambodia's border war with Vietnam, Phim was trusted with one of the most crucial lines of defense.

Only Highway One, to the south, which skirts the southern boundary of the Eastern Zone and connects Saigon to Phnom Penh, was considered as important. Highway One cuts through Svay Rieng province and the area known as the Parrot's Beak, the scene of some of the bloodiest fighting for American as well as Vietnamese and Cambodian troops.

By this time the Center had settled upon the full dimensions of its embellished conflict with Vietnam. The Vietnamese, in this final theory, were not only acting upon their traditional impulses to grab Cambodian land and annihilate the Cambodian people, they were also acting as stalking horses for the Soviet Union. Whether by conscious design or not, this wider war suited Pol Pot's psychological and political purposes. It meant Pol Pot was taking on one of the world's superpowers again. Just as he and the party claimed to have defeated the United States in the earlier war, now they claimed to be beset by the other superpower. It fit the party's psychological need to be at the center of the world's conflict, to view themselves and their country as the prize other powers covet.

In a far more practical and frightening fashion, they raised the stakes of the war by claiming it to be an expression of the Sino-Soviet split. They probably needed little prodding from Beijing in this respect. The Chinese publicly had warned the world at large and the United States in particular that a full U.S. withdrawal from the region after 1975 would be an open invitation for Soviet expansionism. The Chinese had predicated peacetime aid to Vietnam on the demand that the Vietnamese decry Soviet hegemony, a demand the Vietnamese had refused. Now the Khmer Rouge were fueling a war that the Chinese could say proved their point.

When the Chinese gave the Cambodians new arms they requested in 1977, they renewed their demand that the Cambodian communists come out in the open, declare themselves communists, unveil Pol Pot as the leader of the party and the country, and begin to counteract the bloodcurdling stories being told by refugees who had fled Democratic Kampuchea into Thailand. The price of stepped-up Chinese arms aid and diplomatic support was Pol Pot's agreement to act like a mature government and end his guerrilla mentality, at least in the world of diplomacy. That step was taken in September 1977, on the occasion of the party's birth date.

But Pol Pot got the war under way before the event. The first cross-border raids were in January 1977, in both the Eastern and Southwestern Zones. The attacks out of the southwest continued for several months, but in the east something went wrong. Attacks stopped while purges got under way of local party members who had once been part of the bourgoisie. Furious, small East Zone units either mutinied, fled, or were captured while on reconnaissance in Vietnam. One low-level Eastern Zone soldier who ended up in Vietnam was a young former student named Hun Sen. He was detained by Vietnamese military intelligence. Within a year he became a major figure of opposition to Pol Pot.

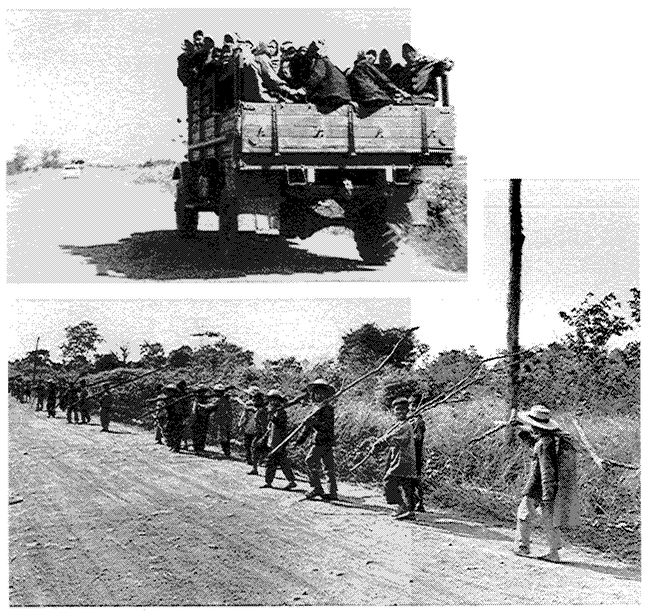

Cambodians going off to the fields during the Khmer Rouge revolution (December 1978).

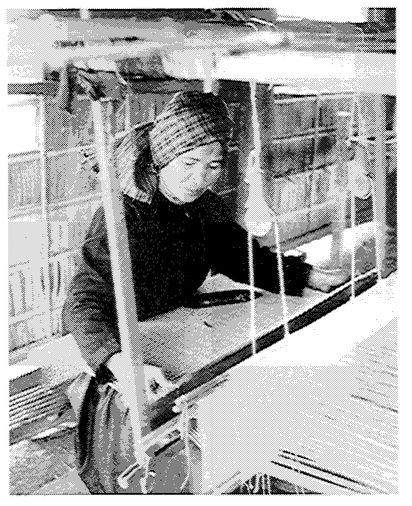

Planting and Harvest (December 1978).

A truckload of young women and young children carrying firewood, both from Khmer Rouge workers brigades (December 1978).

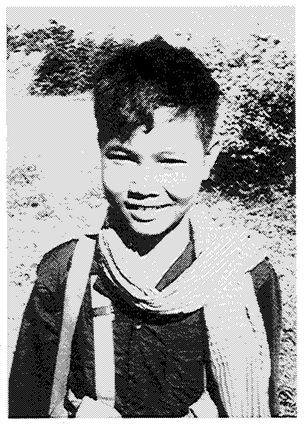

A young Khmer Rouge soldier defending the border with Vietnam in December 1078âone week before the invasion.

Other books

Blood on the Tongue (Ben Cooper & Diane Fry) by Booth, Stephen

Assassin by Lady Grace Cavendish

Unfaithful: An Unlocked Novella by Suzuki Sinclair

Flat-Out Sexy by Erin McCarthy

The Journey Home by Brandon Wallace

Deep by Skye Warren - Deep

G-Spot by Noire

Claimed by the Wolf (BWWM Erotic Paranormal Romance) by Candi Jackson

Going Rouge by Richard Kim, Betsy Reed

Diary of a Stage Mother's Daughter: A Memoir by Melissa Francis