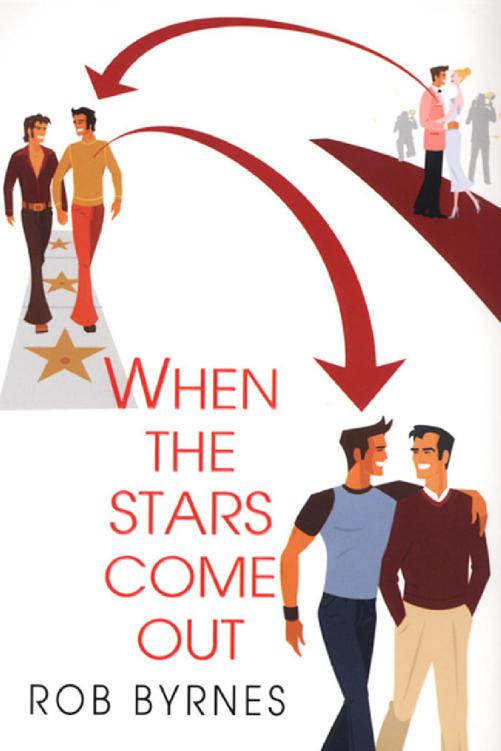

When the Stars Come Out

Read When the Stars Come Out Online

Authors: Rob Byrnes

WHEN THE STARS

COME OUT

Books by Rob Byrnes

THE NIGHT WE MET

TRUST FUND BOYS

WHEN THE STARS COME OUT

Published by Kensington Publishing Corporation

WHEN THE STARS

COME OUT

ROB BYRNES

KENSINGTON BOOKS

Kensington Publishing Corporation

Presents

a Rob Byrnes novel

Noah Abraham

Bart Gustafson

Quinn Scott

Jimmy Beloit

and

Kitty

Randolph

in

WHEN THE STARS

COME OUT

Introduction

My life has had three acts.

Act One began when I was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

in 1934.

Act Two began when I was reborn on a soundstage in Los

Angeles, California in 1969, on the day my eyes met the eyes of a

stranger.

In those first two acts of my life—almost evenly split, chrono-

logically—I led two very different lives. With my youth came a

modest degree of fame; with my middle age came a great degree

of love. And through those two acts of my life, I became a com-

plete individual.

Now, as I enter my golden years, comes Act Three. The third

act is where the plotlines are all drawn together, and you learn if you have been watching comedy unfold, or tragedy.

This is my story

. . .

Los Angeles, California, September 1969

S

tep left. Step left. Turn to the right. Remember to keep a bounce in your

knees. Step right. Turn to the left . . .

He moved across the floor of the soundstage, and hundreds of

hours of rehearsals ran through his head. If he wasn’t particularly elegant or light on his feet, his movements were fluid, showing no trace of self-consciousness.

Turn right. Look at her. Hold the gaze. Smile . . . and . . .

She stopped singing.

Sing.

We have the moon, we have romance,

We have to take this one last chance,

So take my hand,

And take me out,

To somewhere where we’ll see the stars come out.

He sang his five lines to her in an unexceptional yet on-key bari-

tone, and when he was done she picked up the song again. Then,

again, he was dancing the steps that had been drilled into his head and his legs over hundreds—or was that thousands?—of hours of

rehearsals.

Step right. Step right. Turn away. Remember to bounce. Slide to the right.

Turn back. Turn away. Step . . .

He pivoted at the hip to look at her one last time, and when he

turned away from her yet again, well

. . .

That was when their eyes met.

For decades after that moment, they would describe it as “The

Glance.” It was immortalized on film, made timeless by the cameras that captured it that day. But that was just the bonus

. . .

the moment they could replay over and over again, watching themselves

in all their youthful glory.

W H E N T H E S T A R S C O M E O U T

11

More importantly—much more importantly—The Glance would

be forever immortalized in their hearts.

For decades, they would agree that it had been a good day on

the soundstage, which was fortunate, because it was also one of their last days on a soundstage. The Glance began a relationship, ended

another relationship, destroyed some careers, and began others. It drove some people apart and taught others how to love.

But whenever Quinn Scott and Jimmy Beloit thought back to

that day when their eyes locked on that soundstage, it was as if

nothing bad had ever happened in their lives. It was as if theirs

were not the careers destroyed, and they had not been the ones

evicted from Eden.

Because they had found each other. And that, they knew, was all

that was important.

At least, for the first thirty-six years. The thirty-seventh year, on the other hand, would prove to be a bit more problematic.

New York City, September 1970

It was Friday, which meant it was Date Night.

Every Friday since they had returned from their honeymoon had

been Date Night, and this Friday would be no different. Even though the husband was growing slightly bored with the marriage

. . .

even though the wife was growing impressively pregnant with their first child

. . .

even though the night in New York was cold and wet

. . .

it was Friday, and it was Date Night. If it had been a federal law instead of a married couple’s custom, the Friday pattern could not

have been followed more rigorously.

For Max and Frieda Abraham, Date Night followed a pattern

that had, over the five years of their marriage, slowly evolved from a way to keep the relationship fresh into a numbing routine. They

would dress and be out the door of their Park Avenue apartment—

too expensive for their struggling budget, and too far uptown to be fashionable—no later than 6:30. They would indulge themselves

with a cab, when they could find one, and travel to a movie theater somewhere north of Forty-second Street, the demarcation line at

which they felt a cab ride would become cost prohibitive. They

12

R o b B y r n e s

would almost always catch a movie, followed by a late dinner. And, after dinner, they would cab back to the apartment, arriving home

no later than midnight. Frieda would go straight to bed, and Max

would join her an hour or so later, first stopping to pore over the work he inevitably brought home in his briefcase, preparing for another long Saturday in the law office.

After almost 280 Date Nights, they both knew it was growing

stale. Now, on most Date Nights, they barely spoke, except to re-

view the movie they had just seen, or to review the food they were eating. Frequently, they both thought that they should tell the

other that the routine-breaker had become a routine, but then

they thought better of it, under the mistaken impression that their spouse still needed the break and that Date Night somehow continued to keep their relationship fresh and romantic.

Date Night on the third Friday of September 1970 started with a

cab ride through rain-slicked streets to a theater near the Plaza

Hotel, where they watched the colorful Kitty Randolph musical,

When the Stars Come Out

. For a new film, Max thought, it was already dated; a lavish Technicolor musical in 1970 seemed passé by a dozen years or so. American society had been transformed by Vietnam,

Woodstock, rock ’n’ roll, and marijuana. Even the gays were becom-

ing visible in the wake of the previous year’s Stonewall riot. The American musical had transitioned from

Oklahoma

to

Hair

.

But on the screen, girl-next-door Kitty Randolph was still being

romanced by blandly handsome leading man Quinn Scott in a col-

orful, imaginary world devoid of real-world concerns. She was the

new-to-the-big-city ingénue, bravely fighting the corporate struc-

ture in a San Francisco advertising agency and struggling to be

taken seriously as a woman

and

a professional; he was the chauvin-istic ad man won over by her charms and talent. They met, fought,

flirted, fell in love, and, of course, sang unmemorable songs to

each other.

The minor nod to female empowerment aside—already done

better and more effectively by real life—the movie was an anachro-

nistic crowd pleaser. And Kitty Randolph was no longer the fresh-

faced child-woman of her early career. Now somewhere in the gray

area between thirty and forty, her youthful appearance came

largely courtesy of soft focus. All in all,

When the Stars Come Out

had the feel of desperation to it, as if the producers felt they could hold W H E N T H E S T A R S C O M E O U T

13

on to a past that was quickly fading away

. . .

if it had not already disappeared.

Or at least that was how Max reviewed the movie over dinner.

“Not a bad movie, but it feels like it comes from another era.”

Frieda focused on her salad, gently poking the tines of her fork

into iceberg lettuce. It annoyed Max when she did that.

“They’re getting divorced, you know,” she said finally, as she hu-

manely speared a leaf at its corner and dipped it in the salad dressing pooled at the side of her plate.

“Who?”

“Kitty Randolph and Quinn Scott.”

Max had not even known they were married in real life. For that

matter, he had not even cared. Still, Kitty Randolph was America’s girl-next-door, the kind of woman who did

not

get divorced. Even in racy, tumultuous 1970.

“Where did you hear that?”

“I read it,” said Frieda, again gently poking her lettuce leaves.

“In one of my magazines.”

Max sighed. Her damn celebrity magazines, cluttering up the

apartment. He hated them almost as much as he hated watching

her poke the lettuce, and almost as much as he was growing to hate Date Night . . . but, of course, he would not say a word.

Frieda continued. “It’s all very mysterious. No scandal, like Eliza-beth Taylor and Eddie Fisher and that poor Debbie Reynolds. They

just . . . split up. One day they were together, and the next, he was gone.”

“He walked out on her?”

“He walked out. Or so they say. I read that he’s quitting the movies and moving to Long Island or something. I think he has a house out there.”

Max immediately decided that Quinn Scott was his hero. Any

man who could just walk away had to be heroic, because most

men—even hard-driving fourth-year associates at major law firms,

like Max—were trained to just sit back and endure it for the rest of their lives. Like Max, they would marry at twenty-six, decide it was a boring mistake at thirty, and live silently with that mistake for another forty or fifty years.

True, Quinn Scott was not just any man. He was, like his wife, an

actor, although not nearly as accomplished. He was that guy who

14

R o b B y r n e s

you sort of thought you knew from supporting roles in John Wayne

movies or insipid comedies, which, while not superstardom, put

him leagues ahead of all the actors you

didn’t

sort of think you knew. And for three years in the ’60s he had played the lead in television’s moderately popular crime drama

Philly Cop

, which certainly counted for something, if not quite immortality.

So quitting the acting business? Max would believe it when he

saw it. He was probably just diminishing expectations, to better

make a graceful transition back to television. And anyway, there

were worse ways for a man to spend those last forty or fifty years.