When the King Took Flight (24 page)

Read When the King Took Flight Online

Authors: Timothy Tackett

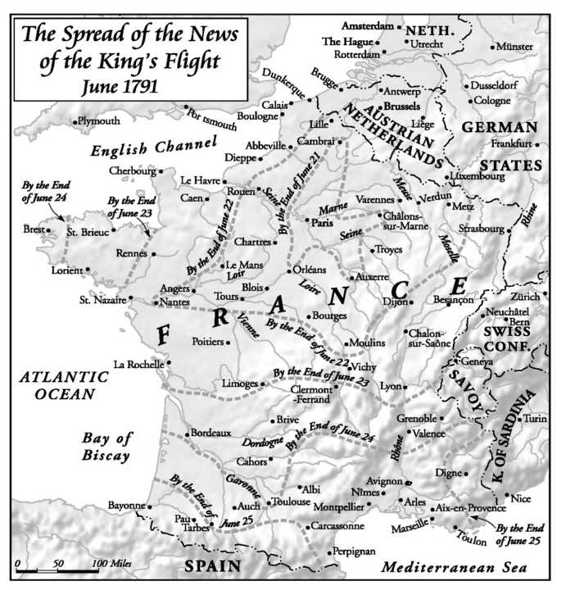

Once Louis and his party had been identified and halted, another wave of news spread out from Varennes in much the same

manner. The master barber Mangin, riding around the clock, had

brought his account to the National Assembly in less than twentyfour hours. But elsewhere the second surge of news often moved

slightly more slowly, perhaps because it first traveled primarily by

the chain of local messengers, until official notification could be relayed from the capital on June 23. It reached Bordeaux only on the

fifth day, Toulouse on the sixth, and Perpignan on the morning of

the seventh day after the king's arrest. In the confusion of currents

and crosscurrents, radiating from multiple sources, many towns

learned of Varennes only a few hours after-and in some cases before-hearing of the king's disappearance from the Tuileries.'

It was one of those events with such a powerful emotional impact that people would remember all their lives where they had been and what they had been doing when they were first informed. Depending on the day and the time when the various messengers arrived, the news caught people in their fields, or at work in their

shops, or marching in Corpus Christi processions, or asleep at

home, awakened by church bells in the middle of the night. In a

number of towns, citizens were in the midst of primary assemblies,

convoked to elect a new legislature, when "the deplorable event of

the king's disappearance threw everyone into turmoil."9 Almost everywhere, as citizens recounted in moving letters to the National Assembly, the unexpected news provoked intense grief, consternation, and stunned incredulity. In the southern town of Auch, "emotions have reached their peak"; in Beauvais, north of Paris, "everyone is filled with intense sorrow over this frightful event which has

afflicted the nation"; in Chateauroux, in central France, "people

sense an abyss of evil and suffer the torments of an agonizing situation." The Jacobins of Montmorillon must have described the feelings of a great many others when they recalled their hopes, on the

eve of Varennes, that the Revolution had at last come to an end,

that threats of counterrevolution had disappeared, that they might

now return to normal lives: "But the disappearance of the king has

crushed all our hopes, and has warned us not to count on such a

return.""

Confronting this unprecedented emergency throughout the country were the officials of the newly transformed regional government. The Revolution had brought a dramatic reorganization and

democratization of the administrative system, with the thirty-odd

intendants, the king's appointed governors under the Old Regime,

replaced by thousands of elected officials. It was they who staffed

the new bureaucratic system into which France was now divided:

the 83 departments, the Soo districts, and the 40,000 municipalities

large and small. With little or no experience in such positions, the

officials had been undergoing massive on-the-job training over the

previous year. At times they had struggled with the sheer number

of new laws and directives passed down to them by the National

Assembly on almost every aspect of economic, fiscal, religious, and

agrarian life. Yet for the most part-especially at the department

and district levels and in the larger towns-the new administrators

were drawn from the educated professional and merchant elites.

They had closely followed and embraced the Revolution from its

beginning, and they were ready, confident, and resolutely determined to perform their duties as best they could.

Jolted into action by the crisis, the officials quickly organized emergency committees, bringing together representatives from the

various power centers in their areas. In a typical regional capitalin Lyon or Beauvais or Auch-the departmental authorities summoned deputies from the district directory and the local municipal council, as well as from the principal law courts, the patriotic

clubs, the national guard, and the regular army. If a town was divided into neighborhood sections-as was the case in the largest

municipalities-or if the electoral assemblies happened to be meeting, these bodies, too, were invited to send representatives. Thus, in

the northeastern town of Thionville over a hundred people had

crowded within minutes into the mayor's office, the largest assembly space available, where many of them remained around the clock

for the next three days."

Whether or not this collective approach to crisis management

was the most efficient means available, it did provide a muchneeded sense of unity and solidarity. Especially in the larger communities, where multiple levels of authority existed side by side,

fierce rivalries had often arisen during the previous year-between

department and district, or district and town, or department and

town.12 But now, confronted with this stunningly unexpected emergency, officials everywhere made unity and cooperation their highest priorities. Numerous patriots attested their newfound sense of

harmony in letters to the National Assembly. "There exists in this

town," wrote the leaders of Dieppe, on the English Channel, "the

greatest possible unity between the different bodies holding power."

In Lyon patriots were convinced that their security depended on

"the rapid unification of all authority, and on the general confidence

which such power will inspire."" To reinforce the sense of common

purpose, the town of Saint-Quentin required all men and women to

wear specially manufactured ribbons with the words "Union! Live

free or die!" Indeed, in a number of towns local authorities ordered

all citizens to affirm their solidarity by displaying Revolutionary

cockades, the tricolor bull's-eye badge that had become one of the

symbols of the patriots in Paris.'

Even more dramatic emblems of unity were the emotion-filled oaths organized by people almost everywhere as soon as they

learned of the king's disappearance. Residents of the small town of

Juillac, in central France, meeting in their electoral assembly, vividly recalled the moment the news arrived. At first they all sat

stunned in "mournful silence." Suddenly the president of the assembly rose to his feet, raised his hand to heaven, and pronounced

an impassioned oath: "I swear to defend to my last drop of blood

the nation, the law, and the National Assembly. I swear to live free

or die!" Immediately all the others present stood, raised their hands,

and shouted in unison: "I, too, so swear." Everyone then filed out

of the room, sustained with a new sense of purpose, and walked to

the city hall, where members of the local Jacobin Club and the national guard took a similar oath.15

In town after town, civic leaders and common citizens, men and

women, old and young, national guardsmen, soldiers, and even a

scattering of patriot nobles and clergy-all clamored to enunciate

oaths of their own. They did so spontaneously, for the most part,

even before learning of the similar declarations sworn with such

fervor in Paris on June 23. And in most cases they replaced "king"

with "National Assembly" in the oath formula that had previously

been used. In Valenciennes, near the Austrian border, "we all swore

to shed our blood for the defense of freedom and the happiness of

the nation." In Tours the ceremony took place out of doors near

the Loire River, with "a thousand voices" uniting in a vow to sacrifice their lives for the preservation of the constitution. Beneath the

walls of Saint-Malo, on the Breton peninsula, 4,000 armed guards,

along with 2,000 women and children, swore their allegiance to the

nation and the constitution. In Cahors, in south-central France,

oaths were also pronounced by women as well as men, each occupying a separate space: "the women, standing nearby in the garden

imitated the men, repeating in a touching manner their affirmations

of fraternal and patriotic love.""

In their near obsession with oathtaking in a moment of crisis, the

French were using a symbolic language with which almost everyone

was familiar. They lived in a world in which solemn vows of this sort retained a religious character and remained requisite acts for

entry into the army, the clergy, or the law courts. Those with any

education were also familiar with the oathtaking tradition of classical Greece and Rome-a tradition given new immediacy by the

stirring oaths of the National Assembly at the beginning of the

Revolution. The oath of June 1'7, 1789-when the Assembly was

created-and the Tennis Court Oath three days later had been

widely publicized, inspiring the whole nation to excited emulation.

Even more pervasive had been the waves of oathtaking in February

and July 179o-the latter as part of the federation ceremonies celebrated throughout the country. But the earlier oaths had always

been somewhat abstract, pronounced in moments of general calm.

Now the French found themselves facing the very real danger of invasion and war. It was in this context, in a moment of great tension,

that they frequently attached the coda "to live free or die." For people who were now confronted with the prospect of living in a nation without a king, the one individual who had always represented

the unity of that nation, oathtaking held an additional relevance. It

was the visible symbol of patriotic union and a willingness to work

together and die together for the greater good of the national community. In this way, the great surge of oathtaking in June 1791

played a major role in easing anxiety and instilling a sense of common purpose." It was a signal moment in the emergence of French

nationalism.

But oaths of allegiance and a determination to die for the country

were hardly sufficient in themselves to confront the crisis. Emergency committees throughout France were faced with the need to

organize an immediate response to the various dangers their communities might encounter. The National Assembly's initial decrees

provided only the roughest outline for action. The printed proclamation sent out on June 22 ordered administrators to halt all movement across frontiers of people, arms, munitions, precious metals, and horses, and "to take all necessary steps for the maintenance of

law and order and the defense of the nation."18 But there would be

enormous variation from region to region in the ways in which local people interpreted and implemented those decrees.

For towns adjoining coastlines or foreign frontiers, the most immediate concern was the threat from abroad. For a great many people, both in Paris and in the provinces, the implications of the king's

flight seemed obvious. Whether Louis had left of his own will or

had been abducted, everyone expected him to leave the country.

And once the royal family had crossed out of France, war seemed

an inevitable consequence. For the town of Mezieres, only a few

miles from the frontier, the flight could only have been "assured

through the authority of the house of Austria, which now reveals

its clear intention of waging war on France." The town leaders of

Dole, close to the Swiss and German borders, generally agreed: "At

present, we should consider ourselves to be in a time of war and of

imminent peril." And they issued detailed instructions for the mobilization of the whole society, establishing procedures by which all

citizens were to contribute both time and money for the defense of

the nation."

Almost as soon as they learned of the crisis, leaders in frontier or

coastal areas sent out units of the national guard and the regular

army to establish lines of defense and brace for invasion. The city

of Strasbourg took the initiative in stationing guardsmen up and

down the Rhine. Longwy, on the northern frontier near Luxembourg, urged all border communities to arm themselves and prepare

for war. In Provence a protective cordon was set up along the

neighboring Italian states, and in Perpignan detachments were directed to guard both the passes of the Pyrenees and the Mediterranean coast near Spain. Similar steps were taken along the Atlantic

coast. Bordeaux and Dieppe temporarily closed their ports, going

well beyond the instructions from Paris. Rouen established observation posts on the English Channel from Le Havre to the department

border at Le Treport. A semaphore chain was prepared along the

south Breton coast to relay word quickly of suspicious sightings.20 But even in locations a considerable distance from coasts or frontiers, citizen militias were called up for service to patrol the streets

and guard city gates and bridges. Rusty cannons were dragged into

position to defend local stores of ammunition and strongboxes containing public funds. Barricades were established at central positions-the city hall, the courthouse, the offices of the department

and the district-to protect against the uncertain threats that everyone feared but no one could quite name.21

The situation was particularly tense in the northeastern sector of

France. This was the zone traversed by the king in his attempted escape, and it took no feat of genius to conclude that he had been

heading for the border of the Austrian Netherlands. Since General

Bouille and his entire general staff had deserted to the enemy, the

armed forces in the region had been left leaderless, and civilian authorities had to step in and improvise as best they could.22 All along

the frontier, from Metz to Givet and Rocroi, volunteer citizens' brigades and patriot soldiers rushed to shore up the frontier fortresses,

left in disrepair since the previous war thirty years earlier. In Sedan

city administrators even organized a special festival dedicated to the

defense of the fatherland, a festival that conveniently coincided

with the Corpus Christi ceremony. After the celebration some three

thousand citizens, joined by infantrymen garrisoned nearby, set to

work repairing the walls and moats protecting the town.23