When the King Took Flight (15 page)

Read When the King Took Flight Online

Authors: Timothy Tackett

Although the king liked to imagine that the unrest in Paris since

1789 was the work of a small minority of Jacobins and rabblerous-

ers, there is ample evidence of the Revolution's impact on all levels of Parisian society. Foreign tourists passing through the city in 1790

and 1791 invariably commented on the outward signs of this transformation: the political discussions taking place in the streets, even

among strangers; the tricolor patriot badges, or cockades, worn by

virtually all men and women; the Revolutionary newspapers and

brochures sold and distributed everywhere; and the patriotic songs

intoned during intermission at the popular theaters and the Opera.'

This politicization of Parisian daily life was part of a Revolutionary

process not unlike that which had affected the peasants and townsmen of Varennes over the previous two years. Almost everywhere,

the National Assembly's onslaught against Old Regime institutions

in the name of popular sovereignty and equality had encouraged

men and women to question authority and injustice more generally.

But in Paris the corrosive logic of democracy and equality had rapidly pushed some segments of the population toward near-millenarian expectations for a radical transformation of the world.

This exceptional radicalization was linked, first, to the city's

eighteenth-century experience as a veritable cultural battleground.

The political struggles of the French Parlements against the fiscal

and religious policies of the monarchy, the dissident movement of

Jansenism against the Catholic establishment, and the intellectual

struggles of Enlightened philosophers against clericalism and obscurantism in any form had all been more intense in Paris than

anywhere else in France or in Europe. Indeed, the city was the recognized capital of the Enlightenment, drawing intellectuals from

throughout the Atlantic world to its salons and cafes and editorial

houses. These complex and often contradictory movements affected

many elements of the unusually literate, highly educated Parisian

population, helping to create an atmosphere of critical and independent thought.

But the radicalization of Paris was also tied to more recent developments. By early 1791 Paris had been saturated with dozens of

daily newspapers and numerous other sporadic publications. Such

papers articulated almost every position on the political spectrum.

In many sections of the city the tone and content of debate were increasingly influenced by a group of exceptionally talented radical writers-like Camille Desmoulin, Jean-Paul Marat, Nicolas de

Bonneville, and Louise Keralio and her husband, Francois Robert-who advocated ever more expansive democratic and egalitarian principles.' Throughout most of France newspapers, radical or

otherwise, had little direct effect on the great majority of men and

women, who had only minimal access to the printed word. In Paris,

however, not only was functional literacy exceptionally high, but

there were other means by which even the illiterate had access to

the latest political commentary. Those who frequented any of the

seven-hundred-odd cafes in the city might hear papers and brochures read aloud and commented on nightly by one of the selfappointed "head orators" who held sway in such establishments.'

Others were informed-or misinformed-of the affairs of the day

by the hundreds of pamphlet and newspaper hawkers roaming the

streets. They continually shouted out the "headlines," or gave their

own sensationalist interpretations of those headlines, the better to

sell their copies. William Short, the protege of Thomas Jefferson

and the American representative in Paris, was amazed at the extraordinary influence of the popular newspapers: "These journals,"

he wrote to Jefferson, "are hawked about the streets, cried in every

quarter of Paris and sold cheap or given to the people who devour

them with astonishing avidity." Mercier was appalled by the potential influence of the paper sellers, many of them actually illiterate:

"Simple legislative proposals are transformed into formal decrees,

and whole neighborhoods are outraged by events that never took

place. Misled a thousand times previously by the false announcements of these peddlers, the common people continue nevertheless

to believe them."6

Finally, Parisian radicalism had been influenced since the beginning of the Revolution by an exceptional proliferation of political

associations. We have already seen the influence of the local patriotic club in Varennes and in the surrounding towns. In Paris, at the

moment of the king's flight, there were no less than fifty such societies.' A few of these groups-like the majority of clubs in the prov inces-were relatively elitist, with elevated dues limiting the membership to the middle or upper classes. Such was the case of the

celebrated Jacobin Club, which met on the Right Bank not far from

the National Assembly and the Tuileries palace, and which was the

mother society for a whole network of "Friends of the Constitution" throughout the kingdom. Yet many of the Parisian clubs had

been created specifically to attract the more humble elements of society, those "passive citizens" whom the National Assembly had excluded from voting and officeholding by means of property qualifications.

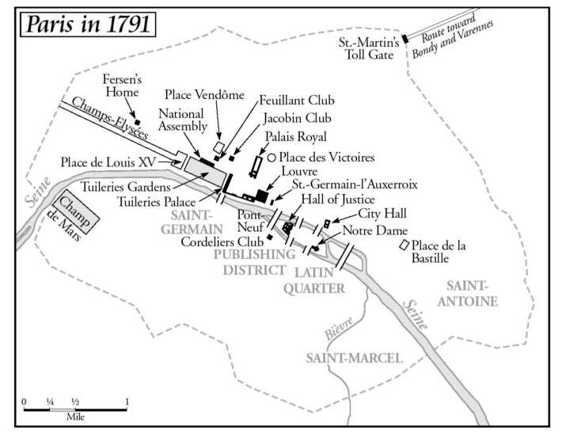

No Parisian group was more active in recruiting the lower classes

into political participation than the Society of Friends of the Rights

of Man, best known to history as the Cordeliers Club. Meeting

on the Left Bank, near the Latin Quarter and in the heart of the

publishing district, its members consisted of a group of radical

intellectuals-men like Desmoulins, Marat, Robert, and Georges

Danton-and a substantial contingent of local merchants and artisans, both men and women. From the beginning the Cordeliers pursued a dual agenda: on the one hand, to promote the expansion of

democracy and equality and to defend the rights of the common

people; and on the other, to root out the plots and conspiracies that

most members believed were threatening the Revolution.' But this

club was only the oldest and best-known of thirty-odd "fraternal societies," popular democratic associations that had emerged in

Paris in 1790 and 1791. Some of these had grown up around individuals with aspirations to leadership in particular neighborhoods

of the city. Others-like the Fraternal Society of the Indigenthad been promoted by the Cordeliers themselves in early 1791, with

the specific intention of mobilizing the masses in support of their

brand of egalitarian politics. All the fraternal societies sought to obtain the right to vote and to hold office for all men, not just for those

with property. Several also permitted participation by women, some

of whom were urging an increasing role for female patriots more

generally. By the spring of 1791 Francois Robert and the Cordeliers

were attempting to coordinate the activities of all such societies around a "Central Committee." The Friends of the Rights of Man

were thus well on the way to creating a Paris-based network of political clubs closely paralleling the national network of the Jacobins.'

A second set of urban associations had developed around the

forty-eight "sections" of Paris. Created in the spring of 1790 to replace the older "districts," the sections had been designed as electoral units for the periodic selection of officeholders. But by early

1791 they were meeting almost continuously, assuming control over

an array of neighborhood affairs, and frequently voicing opinions

on the political issues of the day. Although membership was limited

to "active" male citizens, the leadership cultivated close ties with

the local communities, lending them a certain grassroots character.

Indeed, many of the sections with large working-class constituencies adopted egalitarian and democratic positions not unlike those

of the Cordeliers Club and the fraternal societies. Their power and

influence grew even greater after they began communicating with

one another and holding joint meetings to coordinate policies. By

the spring of 1791 both the sections and the fraternal societies were

becoming organs of influence increasingly independent from the

National Assembly and the regular Paris municipal government.10

In the months preceding the king's flight, a series of developments had left the neighborhoods of Paris ever more nervous and

suspicious. A great wave of strikes and other collective actions by

workers kept the city in near-constant turmoil throughout the winter and spring. Working men and women were disturbed, in part, by

the rapidly rising prices, triggered by the great quantities of paper

money being printed by the government. Yet the unrest could also

be linked to the Revolutionary process itself, as journeymen workers applied the same egalitarian logic to the labor system that others

had used against the political and social systems. Many of these

workers had been encouraged in their struggles in March 1791,

when the National Assembly formally abolished the guild system,

an institution that had given so much authority to the master craftsmen. Only a few days before the king's flight, however, the Assem bly passed a decree far less favorable to the workers, the famous Le

Chapelier law, which outlawed worker associations and collective

bargaining."

Lower class and middle class alike were also unsettled by continuing rumors of counterrevolutionary plots. Fears had been aroused

by the blustering pronouncements of emigrant nobles, threatening

to invade from across the Rhine, and by the very real and well-publicized conspiracies hatched during the first two years of the Revolution. Such tensions were exacerbated by the large numbers of

aristocrats living in the city, many of them with their own reactionary clubs and publishing houses, closely attached to the conservative minority in the Assembly itself. The creation of a Monarchy

Club at the end of 1790, with a membership drawn largely from the

nobility and clergy, seemed tangible evidence of a conspiracy to reinstate all the abuses of the Old Regime. Perhaps even more disturbing was the religious schism set in motion by the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and the requirement of an ecclesiastical oath.

Some 34 percent of the parish clergy in the capital and its suburbs

had rejected the oath. For the Parisians, as for the people of Varennes, the "refractory" clergy became a visible symbol of the

counterrevolutionary forces lurking in their midst. The fear of conspiracy hatched by refractories or aristocrats was a primary cause of

numerous riots in Paris throughout the winter and spring."

The responsibility for reining in and controlling this tense and

turbulent city had fallen to two key figures in municipal politics,

both chosen from the National Assembly itself in July 1789: the

mayor, Jean-Sylvain Bailly; and the commander of the national

guard, the marquis de Lafayette. Renowned astronomer, member

of the prestigious French Academy, and onetime friend of Voltaire

and Benjamin Franklin, Bailly had made his political reputation as

the exceptionally able first president of the National Assembly.

The much younger marquis-only thirty-three at the time of Varennes-was well known not only for his exploits in the American

Revolution but also for his involvement in a variety of liberal

causes in France on the eve of the Revolution. In 1791 Bailly and Lafayette had at their disposal over 50,000 national guardsmen.

Some io,ooo of these forces-most of them former military menwere on permanent duty, paid and living in barracks. The remainder were volunteer citizen soldiers, serving only by rotation or in

moments of emergency. Because the volunteers were required to

provide their own uniforms and to have enough free time for a

smattering of drills, the majority came from the middle class." Although the total force seemed imposing, and was vastly greater than

anything existing under the Old Regime, it was not without its

problems. The same suspicion of authority that had beset the regular army was having its effect on the national guard. The refusal of

some contingents of the guard to allow the royal family to leave the

Tuileries on April 18-despite Lafayette's formal order-was revealing in this respect. But in the aftermath of the April 18 incident,

the general had been given a free hand to reform the corps, and

stronger discipline had been imposed with the dismissal of the insubordinate guardsmen.'

Throughout the first half of 1'791, the guard had been continually active, intervening almost daily in a variety of worker protests,

market brawls, and insurrections against clergymen or nobles rumored to be plotting counterrevolution and civil war. Both Parisian

observers and foreign visitors were obsessed by the incessant turmoil, the ever-present threat and reality of social violence besetting

the city, violence of which February 28 and April 18 were only the

most dramatic instances. "Tumults happen daily," wrote the British

secret agent William Miles: Lafayette and his subordinates were

"kept trotting about like so many penny-postmen." The English

ambassador, the earl George Granville Gower, reported on "the absolute anarchy under which this country labours." William Short

felt that the endless disturbances cast "a gloom and anxiety on the

society of Paris that renders its residence painful in the extreme."

The elderly Parisian Guittard de Floriban had much the same feeling: "Can't we ever be happy," he pleaded, "to simply live together

in peace with one another? All this violence leaves me overwhelmed

and depressed."15 On the eve of Varennes Paris was already in danger of exploding from one day to the next.