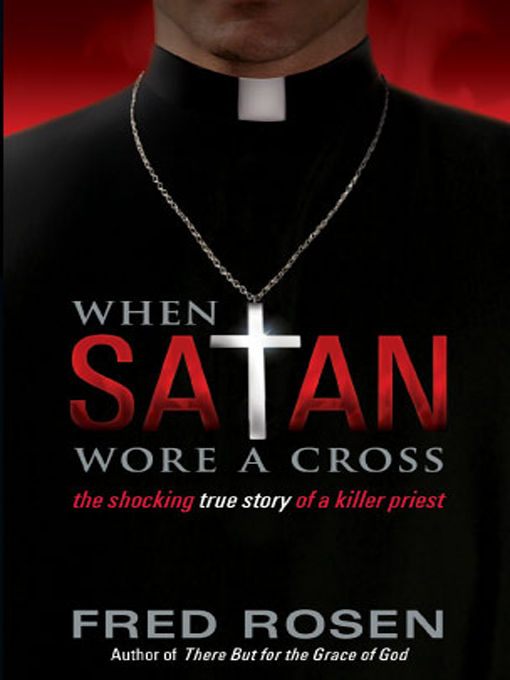

When Satan Wore a Cross

Fred Rosen

For Greg Rose for his support,

Allison Hock for her inspiration,

and both for their friendship.

…sooner or later, somewhere, somehow, we must settle with the world and make payment for what we have taken.

F

RAN

S

TRIKER

From the cowardice that shrinks from new truth, From the laziness that is content with half truths, From the arrogance that thinks it knows all truth, O God of truth, deliver us.

H

UGH

B. B

ROWN

This book is based upon on-the-spot reporting and interviewing in Toledo, Ohio, follow-up interviews, official court and police documents, and other background research materials, including published news accounts.

Dialogue has been reconstructed on the basis of the participants’ recollections, as well as the official record of the case. In a few instances, the names of people, and some background information in their lives, were changed to protect anonymity. Where public documents have been reprinted, personal and identifiable information have been deleted.

June 4, 2006

They threw my bag off the train about dawn.

It was the headline a month earlier that had gotten to me: “Priest Kills Nun.” If it was true, it was a first in American criminal history.

Reverend Father Gerald Robinson, sixty-eight years old, had been accused of murdering seventy-one-year-old nun Sister Margaret Ann Pahl twenty-six years earlier in 1980. It was a cold case, the cable channels trumpeted, solved by modern forensic science. The prosecution had approached trial with great confidence, the defense with great diffidence.

Every day, national TV covered the day’s events in the courtroom. The prosecution alleged that Father Robinson murdered Sister Pahl because there was “bad blood” between them. Pushed to the breaking point, he strangled and stabbed her more than thirty times. That’s a lot of anger. The trial included testimony from an exorcist—yes, an exorcist—who told the jury that the killer carved an inverted crucifix into Sister Pahl’s chest.

The inverted cross is a satanic symbol used in the Black Mass of the Middle Ages. A parody of the Catholic Mass in which the supplicant worships Satan or one of his demons, the Black Mass is celebrated

backwards

, with the last ritual practiced first and so forth. The ritual of how to blaspheme the cross is left up to the supplicant. One way is to spit on it, another to invert it. Even after conviction, it wasn’t clear if Father Robinson was indeed a Satanist who had practiced the Black Mass.

None it of it made any sense.

I had boarded in Albany the afternoon before and settled into my seat for the eleven-hour ride on the Lake Shore Limited to Toledo. Outside the window, the forests of the upper Catskills rushed by, seeming to bloom dark green before my eyes. Late afternoon sunshine waned into the blue light of dusk. The train passed over a river that became a black sea stretching into impenetrable darkness. Passengers dozed into the night, awakened only by the conductor announcing upcoming stations.

Toledo is in the upper northwest corner of Ohio. Its access to the Maumee River, which connects to the commercially vital Lake Erie, made the city a major economic prize to the state that possessed it. In the nineteenth century, Michigan and Ohio put in bids for ownership; Ohio won.

“Toledo, next!” the conductor’s harsh voice cut into the early morning darkness.

The train passed a crossing. A moment later, the engineer applied the brake and the train glided on silent rails into the Amtrak station. Jumping down, I grabbed my bag and picked my way gently across two sets of tracks set in gravel before reaching the station platform and, beyond it, the empty waiting room. There were no cabs at the curb, but the station agent, behind a long faux marble plastic counter lit from above by unearthly fluorescents, readily volunteered to call one.

“Alex can use the fare,” she said, referring to the local cabdriver on duty.

“That’s awfully nice of you to call. They wouldn’t do that in New York.”

She laughed.

“You’re in the Midwest.”

Alex pulled his cab up a ramp and into a gray twilight that brightened over a strange urban landscape. On the shores of the Maumee River were the colorful, architecturally futuristic headquarters of the Dow Corning company. On the other side of this huge boulevard was some sort of combination of old brick buildings saved from the wrecker’s ball because someone had rented them, and empty lots.

The cabbie turned into Erie Boulevard. Despite extensive renovations meant to make them attractive to merchants, most of the storefronts were vacant. I wondered if Ohio might want to sell the place back to Michigan.

“The murder trial of the priest got things going a little,” said the clerk behind the counter of the Radisson. “The cable TV people were here a long time and everyone else. Now it’s quieted down ever since the verdict.”

What the clerk didn’t know was that since the trial, a new accuser had come forward. Identified in court documents as “Jane Doe,” she claimed that Robinson raped, sodomized, and did all kinds of unspeakable acts to her during satanic ceremonies for a number of years when she was a child. Jane Doe’s case was coming before the court tomorrow.

It was a Sunday, which just made the downtown deader than usual. There was no diner to go to for coffee, no place for a sandwich, nothing within a half-mile trek across hostile territory. Toledo’s homicide rate is one murder per 10,042 people, more than 30 percent higher than New York City’s. From my tenth-floor room, I looked out as the daylight quickly overtook the decrepit buildings, giving it all a slight glow, like there was something there worth killing over.

I pulled heavy drapes, blocked out the new day, and got into bed, wondering how Sister Margaret Ann Pahl had come to be the unluckiest of the Toledo 10,042.

1909

Long before the medical examiner’s knife enters her thorax, a female murder victim starts out as somebody’s daughter.

President Taft had just installed his jumbo girth in the White House. Back in his home state of Ohio, the rural hamlet of Edgerton had not yet been completely wired for electricity. It was in Edgerton that Margaret Ann Pahl came into the world on April 6, 1909. Margaret Ann was the fourth of nine children born to farmers Frank and Catherine Pahl.

Devout Catholics, the Pahls followed all the precepts of the Catholic Church and believed faithfully in the seven sacraments within which Christ dwells: baptism, confession, the Eucharist, confirmation, marriage, holy orders (ordination to the ministry), and extreme unction (anointing the sick, dying, and dead). The Pahls believed in passing on these beliefs and values to their children.

As Margaret Ann grew older, she attended Catholic school, where she learned that of the seven sacraments, the most important was the Eucharist. At first glance, the Eucharist is simply a wafer and some wine. But during the third part of the Catholic Mass, the Liturgy of the Eucharist,

transubstantiation

takes place. When the priest says the Eucharistic Prayer over the wafer and wine, they transubstantiate, or change literally into the body and blood of Christ, which are then ingested by the parishioners who come forward to take Communio.

During her growing-up years, Margaret Ann took Communion many times. She discovered that after Mass, the consecrated hosts were placed for 363 days in the tabernacle. The tabernacle is a fixed lock box usually placed on the main altar of the church. It was there almost all year for parishioners to venerate. Only on Good Friday, the day Christ was crucified, and on Holy Saturday, the day before his Resurrection, was the Eucharist stored in the sacristy, the dressing room adjacent to the church chapel. Such detail fascinated Margaret Ann and made her feel part of something greater than herself.

Margaret Ann finished high school shortly after her eighteenth birthday in 1927. While America blithely danced the Charleston away into the Great Depression, and Calvin Coolidge made less money than Babe Ruth precisely because of that, Margaret Ann had decided to serve her Lord. It is hard to say exactly when, but by the time she finished high school, it was clear to family and friends alike that she had been touched by God’s vision for her life.

Margaret Ann would serve him by becoming a novitiate in the Sisters of Mercy, the order founded by Catherine McAuley in Dublin, Ireland, a century earlier. Margaret Ann had been divinely inspired by no less a person than the nineteenth century’s Mother Teresa.

Such is Catherine McAuley’s continued popularity that her image graces the most recent Irish five-pound note. The painting on the bill shows a woman with piercing black eyes, a long aquiline nose, thin lips, and a strong, resolute chin. Catherine is wearing the traditional Sisters of Mercy black and white headdress that would become their trademark.

There was gentleness to Catherine, but behind that piercing gaze was a clear, steely resolve she inherited from her father. Catherine was born September 29, 1787, at Stormanstown House, a private estate in Dublin, Ireland. The first of three children born to James McAuley, Catherine realized early that her father came from an old and distinguished Irish Catholic family that had managed to survive when Catholicism had been all but crushed in Ireland. James McAuley spent more than he could afford to help the poor and infirm. The example was not lost on the young Catherine.

After McAuley died in 1794, his widow couldn’t get her financial affairs in order. Forced to sell Stormanstown House, she moved with her brood to Dublin. There, the

Catholic Encyclopedia

says, “the family came so completely under the influence of Protestant fashionable society that all, with the exception of Catherine, became Protestants. She revered the memory of her father too greatly to embrace a religion he abhorred.”

Tragedy struck the McAuley family yet again when the Widow McAuley suddenly died. The three orphaned McAuley children were passed along to a distant family member who squandered their inheritance. As they were passed along again and again like so much human detritus, each “guardian” did the best he could to drum the Protestant Reformation into their heads.

At first, Catherine flat-out refused—a perilous position for a female orphan without tuppence to her name. A single woman without money or prospects in early nineteenth-century Dublin had no rights. Some of Catherine’s good friends emphatically tried to convince her to support an arranged marriage. Catherine, of course, declined. She was dogged in refusing to be told how to think, let alone what to do.

Finally, in the interests of family peace, she agreed to experience Protestantism before totally condemning it. Her researches only served to reinforce her Catholic beliefs. She didn’t like the Protestant “dissensions and contradictions, the coldness and the barrenness of its spiritual life.” It is at this point that Catherine McAuley should have disappeared into the pages of history. But she didn’t.

A wealthy relative of Catherine’s mother, Simon T. Callahan, suddenly returned from India in 1803. He bought Coolock House a few kilometers outside Dublin, and adopted Catherine. She came to live with her second father on his estate. Soon Catherine showed that she had not forgotten the lessons of James McAuley’s charity.

For the next two decades, Catherine spent some of Callahan’s fortune in the service of the Catholic sick and poor. The compromise was that Callahan, a Protestant, would not allow any Church icons into his home. It was a fair bargain, but Catherine worked on him. On his deathbed in 1822, Callahan’s hard Protestant heart finally melted. Baptized a Catholic, Callahan took his first Communion and then died, leaving his entire fortune to Catherine.

The sudden turn in her circumstances was not lost on Catherine.

Suddenly presented with the financial means to make a difference, she used the rest of Callahan’s money to finance her vision of extreme unction. It took five years, but in 1827, Catherine and two female friends founded a new institution for destitute women and orphans, as well as a school for the poor. While the institution was not directly affiliated with the Church, it was decidedly Catholic in its approach and took its marching orders from the archbishop.

Catherine decided that she and her friends would wear a nunlike uniform—simple black dress and cape flowing to the belt, white collar, lace cap, and veil. Watching the congregation that Catherine had put together, the archbishop could see that the day was coming when it would be part of the Church. How could it not be? The archbishop asked Catherine for a name by which her group could be called.

Given her vision and its success, Catherine must have known that this moment would come. She had evidently thought hard on the matter because she quickly replied, “The Sisters of Mercy.” Catherine decided to adopt the roll-up-the-sleeve-and-get-something-done practicality of the Sisters of Charity with the existential dedication and silent prayers of the Carmelites. She knew that her mission now was to undertake works of mercy for the rest of her life.

The Church, however, felt threatened by Catherine’s continued independence. She looked and acted like a Catholic nun without being one. More importantly, neither Catherine nor her institution was under the archdiocese’s direct control. The archbishop decided that it was time for Catherine to declare her intentions—was hers a Catholic institution or not? The pressure was put on.

Catherine held a meeting with her associates, who now numbered twelve. They voted unanimously to become a Catholic religious congregation. Hewing closely to Catherine’s independent streak, the Sisters of Mercy would be unaffiliated with any existing community of nuns. But now the Sisters of Mercy’s would be part of the Church.

Like other Catholic nunneries, the Sisters of Mercy would lead an ordered and regimented life of prayer, choir, chastity, and poverty. Catherine decided, however, that the Sisters of Mercy would specifically tend to the poor, the destitute, the infirm, and also provide education for those who could not afford it, at a time when most couldn’t.

In 1829, two years after the Sisters of Mercy had opened their doors, the archbishop said a prayer and blessed the chapel, dedicating it to Our Lady of Mercy. Being a nun, though, was a lot more than just saying you were one. You had to become a novitiate at a nunnery and receive the proper religious training. Catherine decided she and two other Sisters of Mercy, Elizabeth Harley and Anna Maria Doyle, would begin their novitiate at George’s Hill, Dublin, on September 8, 1830.

A little more than one year later on December, 12, 1831, they took their formal vows. Thus did Catherine McAuley become Sister Mary Catherine. Appointed first superior of the Sisters of Mercy, she held the post for the rest of her life, until her death at age fifty-four in 1841. By then, the Sisters of Mercy had spread out across the British Isles, into the Commonwealth, including Australia, New Zealand, Scotland, and Canada. At every stop, they became known for their tender kindnesses and good works.

Bishop Michael O’Connor of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, saw how effective the sisters were at helping the poor and sick. He asked for and received help from the Sisters of Mercy. A group of sisters was dispatched from Ireland to Pittsburgh. On December 22, 1843, the Sisters of Mercy opened their first congregation in the United States. By 1847, they took over the management of the first hospital in western Pennsylvania. Eighty years later in 1927, Catherine McAuley’s vision inspired eighteen-year-old Margaret Ann Pahl to get into the backseat of her parents’ Buick touring car to serve God.

Since Edgerton was in the far western part of the state directly abutting Indiana, the trip was a good seventy-five miles east on rutted dirt roads, passing Bowling Green until taking a direct dogleg south. Then it was another thirty miles of spine-jarring “roadway” before getting to the outskirts of Tiffin, Ohio. It was here in the early 1920s that the Sisters of Mercy opened their Ohio novitiate, Our Lady of the Pines. It was Margaret Ann’s final destination.

After dropping Margaret Ann off and seeing her settled into the nunnery, her family turned around and trudged back home. After another bone-jarring hundred-mile trip, they arrived back in Edgerton to find that Margaret Ann had left behind all her material belongings. Patiently and neatly, she had attached notes to everything indicating which sibling got what.

For her part, Margaret Ann never looked back.

As America careened through the twentieth century, the Sisters of Mercy were not far behind, picking up the human detritus that “progress” cast aside. They established a hospital system that they administered across the United States. Trained as a registered nurse, Margaret Ann stayed in Ohio, working within what would become known as the Mercy Healthcare system.

Showing a talent for administration, she became the director of the Sisters of Mercy’s nursing school. Further along in her career, she became administrator at St. Charles Hospital in Oregon, Ohio, right across the Maumee River from Toledo, and Mercy Hospital back in Tiffin. In between, Margaret Ann had a lively social life, visiting nuns throughout the northeast and family back in Edgerton, and taking trips throughout the northeast. She particularly loved Niagara Falls. Margaret Ann loved listening to opera. It was a passion.

During her long career, Margaret Ann, a trained nurse, would have noted that alcoholism was a problem for some priests, and that those who couldn’t control their drinking wound up reconciled to backwater parishes and assignments. In Toledo, Mercy Hospital was one of those backwater parishes. Of the two hospital priests, Jerome Swiatecki was a known alcoholic. Staffers talked of Gerald Robinson being more of a private drinker. As for the venue, Catherine McCauley’s spiritual heirs had their work cut out for them.

Mercy Hospital was located in a high-crime area, serving a predominantly low-income African-American population. On Friday and Saturday nights you had to take a ticket to get into the emergency room. Gunshot and knife wounds came first. The place served a desperate, disenfranchised community. In the middle of it all were the Sisters of Mercy who administered the hospital.

The one place to get away from this emotionally charged atmosphere was the hospital chapel, a small affair, set up in traditional Catholic style. Four rows, of two wooden chairs each, faced the altar up front, the tabernacle to the side and behind, and on the right, the sacristy. The chapel had two entrances, one behind the altar and one inside the room itself. The one in the room, Margaret Ann soon discovered, took you through a clean, sterile white corridor that led to a stairwell. The stairwell connected to the dormitory area, where many of the people who worked in the hospital, including the Sisters of Mercy, lived.

In the nuns’ dormitory, there were no private showers or bathrooms. Everything was shared by the sisters. None of the rooms had TVs or phones, except that of Sister Phyllis Ann, the hospital director. It was here, at Mercy Hospital, that Margaret Ann found herself assigned in the twilight of her career.

As she approached her seventy-first birthday in April 1980, Margaret Ann’s hearing had faded. Now partially deaf, she was too proud to wear a hearing aid, and was considering retirement. Her assignments had been reduced to making certain the chapel was in readiness for the priests when they gave their services and making certain the nuns’ dormitory rooms were cleaned.

Shirley Ann Lucas, forty-four years old, was the Mercy Hospital housekeeper, whose job it was to clean the rooms. Sister Margaret would leave open the doors to the rooms to be cleaned. By prior agreement, if any room had the door closed, Lucas would not enter. The only personal rooms she cleaned were those of any guests who occupied the convent and Sister Phyllis Ann’s room.

On Good Friday, April 4, 1980, Lucas was cleaning a guest’s room, when Sister Margaret walked by. They stopped to chat. Lucas had always found Sister Margaret to be a fussy individual who liked things her own way, a very strict and devoted Catholic.