When Do Fish Sleep? (5 page)

Why

Are There More Holes in the Mouthpiece of a Telephone than in the Earpiece?

We just checked the telephone closest to us and were shocked. There are thirty-six holes on our mouthpiece, and a measly seven on the earpiece. What gives?

Tucked underneath the mouthpiece is a tiny transmitter that duplicates our voices, and underneath the earpiece is a receiver. Those old enough to remember telephones that constantly howled will appreciate the problems inherent in having a receiver and transmitter close together enough to produce audible transmission without creating feedback.

Before the handset, deskstand telephones were not portable, and the speaker had to talk into a stationary transmitter. Handsets added convenience to the user but potential pitfalls in transmission. While developing the telephone handset, engineers were aware that it was imperative for the lips of a speaker to be as close as possible to the transmitter. If a caller increases the distance between his lips and the transmitter from half an inch to one inch, the output volume will be reduced by three decibels. According to AT&T, in 1919 more than four thousand measurements of head dimensions were made to determine the proper dimensions of the handset. The goal, of course, was to design a headset that would best cup the ear and bring the transmitter close to the lips.

One of the realities that the Bell engineers faced was that there was no way to force customers to talk directly into the mouthpiece. Watch most people talking on the phone and you will see their ears virtually covered by the receiver. But most people do not hold their mouths as close to the transmitter. This is the real reason why there are usually more holes in the mouthpiece than in the earpiece. The more holes there are, the more sensitive to sound the transmitter is, and the more likely that a mumbled aside will be heard three thousand miles away.

Submitted by Tammy Madill of Millington, Tennessee

.

How

Do Fish Return to a Lake or Pond that Has Dried Up?

Our correspondent, Michael J. Catalana, rightfully wonders how even a small pond replenishes itself with fish after it has totally dried up. Is there a Johnny Fishseed who roams around the world restocking ponds and lakes with fish?

We contacted several experts on fish to solve this mystery, and they wouldn’t answer until we cross-examined you a little bit, Michael. “How carefully did you look at that supposedly dried-up pond?” they wanted to know. Many species, such as the appropriately named mudminnows, can survive in mud. R. Bruce Gebhardt, of the North American Native Fishes Association, suggested that perhaps your eyesight was misdirected: “If there are small pools, fish may be able to hide in mud or weeds while you’re standing there looking into the pool.” When you leave, they re-emerge. Some tropical fish lay eggs that develop while the pond is dry; when rain comes and the pond is refilled with water, the eggs hatch quickly.

For the sake of argument, Michael, we’ll assume that you communed with nature, getting down on your hands and knees to squeeze the mud searching for fish or eggs. You found no evidence of marine life. How can fish appear from out of thin air? We return to R. Bruce Gebhardt for the explanation:

There are ways in which fish can return to a pond after total elimination. The most common is that most ponds or lakes have outlets and inlets; fish just swim back into the formerly hostile area. They are able to traverse and circumvent small rivulets, waterfalls, and pollution sources with surprising efficiency. If they find a pond with no fish in it, they may stay just because there’s a lot of food with no competition for it.

Submitted by Michael J. Catalana of Ben Lomond, California

.

Why

Do We Call Our Numbering System “Arabic” When Arabs Don’t Use Arabic Numbers Themselves?

The first numbering system was probably developed by the Egyptians, but ancient Sumeria, Babylonia, and India used numerals in business transactions. All of the earliest number systems used some variation of 1 to denote one, probably because the numeral resembled a single finger. Historians suggest that our Arabic 2 and 3 are corruptions of two and three slash marks written hurriedly.

Most students in Europe, Australia, and the Americas learn to calculate with Arabic numbers, even though

these numerals were never used by Arabs

. Arabic numbers were actually developed in India, long before the invention of the printing press (probably in the tenth century), but were subsequently translated into Arabic. European merchants who brought back treatises to their continent mistakenly assumed that Arabs had invented the system, and proceeded to translate the texts from Arabic.

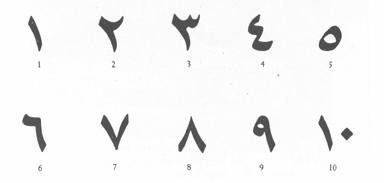

True Arabic numerals look little like ours. From one to ten, this is how they look:

Submitted by Dr. Bruce Carter of Fort Ord, California

.

If you, like every other literate human being, have read

Why Do Clocks Run Clockwise? and Other Imponderables

, then you know why the moon looks larger on the horizon than up in the sky, even though the moon remains the same size. Clearly, our eyes can play tricks on us.

Without reference points to guide us, the moon doesn’t seem to be far away. When you are driving on a highway, the objects closest to your car go whirring by. Barriers dividing the lanes become a blur. You can discern individual houses or trees by the side of the road, but, depending upon your speed, it might be painful to watch them go by. Distant trees and houses move by much more slowly, even though you are driving at the same speed. And distant mountains seem mammoth and motionless. Eventually, as you travel far enough down the highway, you will pass the mountains, and they will appear smaller.

If you think the mountain range off the highway is large or far away, consider the moon, which is 240,000 miles away and bigger than any mountain range (more than 2,100 miles in diameter). We already know that our eyes are playing tricks with our perception of how big and far away the moon is. You would have to be traveling awfully far to make the moon appear to move at all.

Astronomy

editor Jeff Kanipe concludes that without a highway or expanse of landscape to give us reference points “this illusion of nearness coupled with its actual size and distance makes the moon appear to follow us wherever we go.”

This phenomenon, much discussed in physics and astronomy textbooks, is called the parallax and is used to determine how the apparent change in the position of an object or heavenly body may be influenced by the changing position of the observer. Astronomers can determine the distance between a body in space and the observer by measuring the magnitude of the parallax effect.

And then again, Elizabeth, maybe the moon really is following you.

Submitted by Elizabeth Bogart of Glenview, Illinois

.

The calf’s equivalent of a bar mitzvah occurs after it stops nursing, usually at about seven to eight months of age. After they are weaned and/or when they reach twelve months, they are referred to as yearling bulls or yearling calves.

According to Richard L. Spader, executive vice president of the American Angus Association, “calves don’t achieve full-fledged bullhood or cowhood until they’re in production. We normally refer to a first calf heifer at, say, twenty-four months of age or older, as just that, and after her second calf as a three-year-old, she becomes a cow.”

Bulls don’t usually reach maturity until they are three. After they wean from their mothers, they are referred to as “yearling bulls,” or “two-year-old bulls.” Are we now all totally confused?

Submitted by Herbert Kraut of Forest Hills, New York

.

The shifting of clogged nostrils is a protective effort of your nasal reflex system. Although the nose was probably most important to prehistoric man as a smelling organ, modern humans’ sense of smell has steadily decreased over time. The nose is now much more important in respiration, breathing in O

2

to the nose, trachea, bronchi, lungs, heart, and blood, and ultimately the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide. As rhinologist Dr. Pat Barelli explains:

A fantastic system of reflexes which originate in the inner nose sends impulses to the heart and indirectly to every cell in the body. These reflexes, coupled with the resistance of the nose, increase the efficiency of the lungs and improve the effectiveness of the heart action.

The most common reason for congested nostril switching is the sleep process. When we sleep, our body functions at a greatly reduced rate. The heart beats slower and the lungs require less air. Rhinologist Dr. Zanzibar notes that patients

commonly complain that at night when they lie on one side, the dependent side of the nose becomes obstructed and they find it necessary to roll over in bed to make that side open. Then the other side becomes obstructed, and they roll over again.

When the head is turned to one side during sleep, the “upper nose” has the entire load of breathing and can become fatigued. According to Dr. Pat Barelli,

one nostril doing solo duty can fatigue in as little as one to three hours, and internal pressures cause the sleeper to change his head position to the opposite side. The body naturally follows this movement. In this way, the whole body, nose, chest, abdomen, neck, and extremities rest one side at a time.

Bet you did’t know your schnozz was so smart. Our motto is “One nostril stuffed is better than two.”

Submitted by Richard Aaron of Toronto, Ontario

.

Why

Do New Fathers Pass Out Cigars?

“What this country needs is a good five-cent cigar” might have been first uttered in the early twentieth century, but in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, cigars cost much more than five cents. According to Norman Sharp, of the Cigar Association of America, “cigars were so rare and treasured that they were sometimes used as currency.”

Two hundred years ago, a baby boy was considered a valuable commodity. He would work the fields all day and produce money for the father, whereas a baby girl was perceived as a financial drain. At first, precious cigars were handed out as a symbol of celebration only when a boy was born.

By the twentieth century, some feminist dads found it in their hearts to pass the stogies around even when, drat, a girl was born. Now the ritual remains a primitive but relatively less costly act of male bonding—a tribute to male fertility while the poor mother recovers alone in her hospital room.