When Computers Were Human (11 page)

Read When Computers Were Human Online

Authors: David Alan Grier

The almanac was shaped by two individuals, Lieutenant Charles Henry Davis (1807â1877) of the U.S. Navy and Harvard College professor Benjamin Peirce (1809â1880). The two were related by marriage and lived in neighboring houses in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

13

Their front

doors were just a few steps from Harvard Yard; their back windows looked across the fields to the distant ships at the docks of Cambridgeport. Davis's son recalled that children moved freely between the two homes and that their families “dwelt almost as one.”

14

Their friendship had begun some fifteen years before, when Davis had taken a house in Cambridge following an extended voyage. He had once been a student at Harvard College, but he had left without a degree in order to take an officer's commission. During his travels, he had retained an interest in learning. One of his commanders described him as “intelligent in his profession, energetic in his character, and devoted to the improvement of his mind.” While on an early voyage, he studied navigation, learned “French, Spanish and a good smattering of Italian,” and read the complete works of William Shakespeare.

15

In 1840, he had returned to Cambridge for a year of intensive mathematical study with Peirce. According to his son, Davis did not always “follow the transcendent flights of Peirce's genius” but persevered in his study and ultimately acquired “a

working familiarity with mathematical tools.” For his efforts, he received a Harvard degree, conveniently backdated to suggest that he had graduated with his original classmates.

16

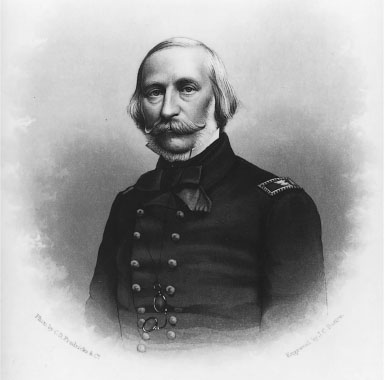

9. Lieutenant Charles Henry Davis of the American Nautical Almanac

By all appearances, Benjamin Peirce was an unlikely friend for Davis. Davis was a practical and disciplined officer from a privileged Boston family. No sign better captured his bearing than his prominent moustache, groomed with military precision. Peirce was one of the “bearded ancients” of Harvard College and sported an unruly head of hair. His lectures were rambling, difficult affairs that were often incomprehensible to students. The one quality that may have caught Davis's sympathy was Peirce's ability to maintain his intellectual bearings. In the 1840s, Cambridge was awash in the Transcendental movement, the philosophical current that saw in every aspect of nature “a symbol of some spiritual fact.”

17

Peirce befriended the leader of the Transcendentalists, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803â1882), and occasionally referred to God as the “Divine Geometer,” but he never lost sight of the theories of Newton or the mathematics of calculus.

18

When the American

Nautical Almanac

began operations in July 1849, the navy appointed Charles Henry Davis as the first superintendent. In turn, Davis selected Peirce as the chief mathematician and established the almanac office in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

19

When called to explain why he did not place the office in Washington, Davis wrote that Cambridge had “the best scientific libraries of the countryâan indispensable aid in laying the permanent foundation of a work of this magnitude and importance.”

20

Davis may have been rationalizing a decision that was convenient for himself and for Peirce, but he clearly wanted to create a superior publication with a staff of “first class computers.” There would be no former hairdressers on his staff and no boy computers like those found at Airy's observatory. He stated that his computers “must be gentlemen of liberal education and of special attainments in the science of astronomy.”

21

At the start, Davis tried to recruit mathematicians for the almanac staff. He wrote to professors at the University of Virginia, Princeton, Rutgers, Columbia, and the Military Academy at West Point, asking each to serve on the almanac staff.

22

To this list he added the name of one foreigner, the French astronomer Urban Jean Joseph Le Verrier (1811â1877). In 1849, Le Verrier was basking in the fame of having discovered the planet Neptune, an event that dominated the public imagination of the 1840s. He was a mathematical astronomer, not an observer, and his discovery was an event of “pure calculation,” “the grand triumph of celestial mechanics as founded on Newton's law of gravitation.”

23

Le Verrier had estimated the location of the planet by analyzing variations in the motion of Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus and by hypothesizing the existence

of an undetected body in orbit around the Sun. He had projected the possible location of this planet and sent his estimate to the observatory at Berlin. The German observers had found the planet with a single night of searching. They waited a second night in order to confirm their observation and then wrote to Le Verrier, “Monsieur, the planet, of which you indicated the position, really exists.”

24

The discovery immediately pushed Le Verrier into public view. Many urged that the planet should be named Le Verrier, just as the comet of 1682 had been named for Edmund Halley. Observers spent their nights studying the barely perceptible motion of the planet and looking for evidence of moons. The news penetrated so deeply into public consciousness that it even reached the backwoods of Massachusetts, where it received a disparaging response from Henry David Thoreau (1817â1862) at Walden Pond. In the manuscript of

Walden

, Thoreau dismissed the mathematics that might allow an astronomer “to discover new satellites to Neptune” but “not detect the motes in his eyes, or to what vagabond he is a satellite himself.”

25

Such words failed to touch Le Verrier's reputation. Had he been willing to join the American almanac staff, Le Verrier would have brought substantial fame and prestige to the periodical, but he declined Davis's request. Davis was ultimately rejected by all of the mathematics professors on his list, save for Benjamin Peirce.

26

To build his computing staff, Davis turned to students, independent astronomers, and skilled amateurs. These individuals were not true members of the country's small scientific community, but each of them had the promise of a successful future. Most of them were either friends or former students of Benjamin Peirce. The list included a young mathematical prodigy from Vermont, Henry Safford (1836â1901); a future president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, John Runkle (1822â1902); and a professor, Joseph Winlock (1826â1875) of Shelby College in Kentucky. Though Davis had not been able to convince the discoverer of Neptune to join the almanac staff, he was at least able to recruit an astronomer who had achieved some fame by computing Neptune's orbit, Sears Cook Walker (1805â1853).

27

In the fall of 1846, the fall when Le Verrier announced the existence of Neptune, Walker was an assistant astronomer at the newly opened Naval Observatory in Washington. This was not a job that he had intended to take, but he had little choice in the matter. For nearly twenty years, he had worked for the Pennsylvania Company for Insurances on Lives and Granting Annuities. By day, he was an actuary, a mathematician responsible for estimating the risk and profit of insurance policies. By night, he was an amateur astronomer, using the telescopes of the Philadelphia High School to study the moon as it passed in front of stars.

28

At the time, the high school observatory was the best equipped in the nation. Most of

the instruments had been donated by Walker, who was making a substantial fortune in his actuarial practice. This life had come to an end in 1845, when a “series of unfortunate investments and commercial operations led to most disastrous results.” According to a friend, this disaster left Walker “at the age of forty years utterly without means.”

29

Under the best of circumstances, Sears Cook Walker could be difficult. “I have had some differences with him,” wrote Benjamin Peirce, “but they have not blinded me to his great merits.”

30

At the Naval Observatory, Walker showed his great skill and his wayward nature. In the fall of 1846, he turned from his observatory duties to consider the planet Neptune. The observatory had been the recipient of small packets of data from the European astronomers, sealed with wax and addressed to the new “National Observatory.” By late fall, he had a substantial collection of data that showed the planet's slow march across the celestial sphere. Walker decided that he might get a better calculation of the orbit if he could find an earlier observation of the planet, an observation that had been falsely recorded as a star. Using the data he had collected, he spent about three months computing the motion of the planet backwards from its location in 1846. He finally found his prediscovery observation in a 1795 star catalog that had been compiled by Joseph Lalande. The catalog showed a star where Neptune should have been. Using the navy's telescopes, Walker sought in vain for the star and concluded that Lalande had seen the moving planet instead of a fixed star. With Lalande's observation, Walker was able to make a refined calculation and show that the planet moved in an orbit that was nearly circular.

31

The navy treated Walker's work as a major triumph, the first important accomplishment of its observatory. “The theory of Neptune belongs, by the right of precedent, to American science,” bragged the observatory director.

32

Ironically, the most well-known of the first computers for the American

Nautical Almanac

was the sole woman, Maria Mitchell (1818â1889). When Charles Henry Davis appointed her to his staff, he presented her credentials to the secretary of the navy as “the lady who lately received from the King of Denmark a medal for the discovery of a new comet.”

33

As an astronomical discovery, the comet was small and unimpressive. It was not even a periodic comet like Halley's. Once it vanished from the night sky, it was gone forever. Still, the discovery caught the public's attention as “one of the first additions to science” made in the United States.

34

Mitchell was an extraordinary scientific talent, and she lived in one of the few communities that acknowledged a public role for women in nineteenth-century America. There were no other female scientists in the United States and few women in any other field of endeavor. She had discovered her comet in 1847, the year before the 1848 Seneca Falls Conference on the Rights of Women, the event that has often been

identified as the start of the American feminist movement. Behind the Seneca Falls Conference lay the Quaker Church, the only religious denomination of the time that allowed women to preach to its congregations. Four of the five conference organizers were Quakers, as were Maria Mitchell and her father, William Mitchell (1791â1869). William Mitchell supported and pushed his daughter in her career, demonstrating what the early feminist Margaret Fuller (1810â1850) called the “chance of liberality” that a father might show to his daughter but a “man of the world” might never show toward his wife.

35

William Mitchell was a banker on Nantucket Island and an amateur astronomer. Maria Mitchell recalled that her interest in astronomy was “seconded by my sympathy with my father's love for astronomical observation.”

36

He taught her how to use a telescope, how to reduce data, and how to compute time from the position of the moon. He was a friend of the scientists at Cambridge, including Benjamin Peirce, Charles Henry Davis, and the director of the Harvard Observatory. When his daughter told him that she had identified a comet, he encouraged her to notify the observatory. When she resisted the idea, William Mitchell communicated the discovery himself. “Maria discovered a telescopic comet at half past ten on the evening of the first instant,” he wrote. “Pray tell me whether it is one of George's [Airy of the Greenwich Observatory]. ⦠Maria's supposed it may be an old story.” The observatory confirmed that the comet was new and initiated an energetic effort to ensure that Maria Mitchell was given credit for the discovery. The object of their effort was King Christian VIII of Denmark. The king awarded a medal to the discoverer of any comet. In the early winter of 1848, he was preparing to give his medal for Mitchell's comet to an Italian astronomer. The director of the Harvard Observatory did everything he could to convince the king to change his mind. He enlisted the aid of the Harvard president and the American consul in Copenhagen. Eventually, the king relented and recognized Mitchell as the first to see the comet.

37

Charles Henry Davis recruited computers through the end of 1849 and began operations that winter. He organized the staff after the pattern that Nevil Maskelyne had established some eighty years before. Each computer took responsibility for one or two tables. Sears Cook Walker took the computations for Neptune. Benjamin Peirce handled the ephemeris of Mars and the apparent movement of the Sun. Without a trace of irony, Davis asked Mitchell to handle the computations for the planet Venus. “As it is âVenus who brings everything that's

fair

,'” he wrote, “I therefore assign you the ephemeris of Venus, you being my only

fair

assistant.”

38

John Runkle, the future president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, prepared part of the calculations of lunar motion, splitting the task with another computer, just as Maskelyne's computers had done.