What to expect when you're expecting (145 page)

Read What to expect when you're expecting Online

Authors: Heidi Murkoff,Sharon Mazel

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Postnatal care, #General, #Family & Relationships, #Pregnancy & Childbirth, #Pregnancy, #Childbirth, #Prenatal care

If neither the prostaglandin nor the stripping or rupturing of the membranes has brought on regular contractions, your practitioner will slowly administer intravenous Pitocin, a synthetic form of the hormone oxytocin (which is produced naturally by the body throughout pregnancy and also plays an important role in labor), until contractions are well established. The drug misoprostol, given through the vagina, might be used as an alternative to other ripening and induction techniques. Some research shows giving misoprostol decreases the amount of oxytocin needed and shortens labor.

Your baby will be continuously monitored to assess how he or she is dealing with labor. You’ll also be monitored to make sure the drug isn’t overstimulating your uterus, triggering contractions that are too long or powerful. If that happens, the rate of infusion can be reduced or the process can be discontinued entirely. Once your contractions are in full swing, the oxytocin may be stopped or the dose decreased, and your labor should progress just as a noninduced labor does.

Eating and Drinking During Labor

If, after 8 to 12 hours of oxytocin administration, labor hasn’t begun or progressed, your practitioner might stop the induction process to give you a chance to rest before trying again or, depending on the circumstances, the procedure may be stopped in favor of a cesarean delivery.

“I’ve heard conflicting stories about whether it’s okay to eat and drink during labor.”

Should eating be on the agenda when you’re in labor? That depends on who you’re talking to. Some practitioners red-light all food and drink during labor, on the theory that food in the digestive tract might be aspirated, or “breathed in,” should emergency general anesthesia be necessary. These practitioners usually okay ice chips only, supplemented as needed by intravenous fluids. Many other practitioners (and ACOG guidelines) do allow liquids and light solids (read: no stuffed-crust pizza) during a low-risk labor, reasoning that a woman in labor needs both fluids and calories to stay strong and do her best work, and that the risk of aspiration (which only exists if general anesthesia is used, and it rarely is except in emergency situations) is extremely low: 7 in 10 million births. Their position has even been backed up by research, which shows that women who are allowed to eat and drink during labor have shorter labors by an average of 90 minutes, are less likely to need oxytocin to speed up labor, require fewer pain medications, and have babies with higher Apgar scores than women who fast. Check with your practitioner to find out what will and won’t be on the menu for you during labor.

Emergency Delivery: Tips for the Coach

At Home or in the Office

1.

Try to remain calm while at the same time comforting and reassuring the mother. Remember, even if you don’t know the first thing about delivering a baby, a mother’s body and her baby can do most of the job on their own.

2.

Call 911 (or your local emergency number) for the emergency medical service; ask them to call the practitioner.

3.

Have the mother start panting, to keep from pushing.

4.

If there’s time, wash your hands and the vaginal area with soap and water (use an antibacterial product, if you have one handy).

5.

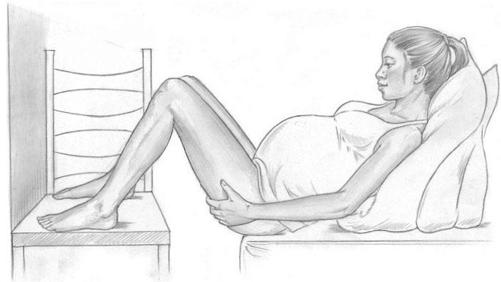

If there is time, place the mother on the bed (or desk or table) so her buttocks are slightly hanging off, her hands under her thighs to keep them elevated. If available, a couple of chairs can support her feet. A few pillows or cushions under her shoulders and head will help to raise her to a semi-sitting position, which can aid delivery. If you are awaiting emergency help and the baby’s head hasn’t appeared, having the mother lie flat may slow delivery until help arrives.

Protect delivery surfaces, if possible, with a plastic tablecloth, shower curtain, newspapers, towels, or similar material. A dishpan or basin can be placed under the mother’s vagina to catch the amniotic fluid and blood.

6.

If there’s no time to get to a bed or table, place newspapers or clean towels or folded clothing under the mother’s buttocks. Protect delivery surfaces, if possible, as described in number 5.

7.

As the top of the baby’s head begins to appear, instruct the mother to pant or blow (not push), and apply very gentle counterpressure to her perineum (the area between the vagina and the anus) to keep the head from popping out suddenly. Let the head emerge gradually—never pull it out. If there is a loop of umbilical cord around the baby’s neck, hook a finger under it and gently work it over the baby’s head.

8.

Next, take the head gently in two hands and press it very slightly downward (do not pull), asking the mother to push at the same time, to deliver the front shoulder. As the upper arm appears, lift the head carefully, watching for the rear shoulder to deliver. Once the shoulders are free, the rest of the baby should slip out easily.

9.

Place the baby on the mother’s abdomen or, if the cord is long enough (don’t tug at it), on her chest. Quickly wrap the baby in blankets, towels, or anything else that’s clean.

Even if your practitioner gives you the go-ahead on eating, chances are you won’t be in the market for a major meal once the contractions begin in earnest (and besides, you’ll be pretty distracted). After all, labor can really spoil your appetite. Still, an occasional light, easy-to-digest snack during the early hours of labor—Popsicles, Jell-O, applesauce, cooked fruit, plain pasta, toast with jam, or clear broth are ideal choices—may help keep your energy up at a time when you need it most (you probably won’t be able to, or won’t want to, eat during the later parts of active labor). When deciding—with your practitioner’s help—what to eat and when, also keep in mind that labor can make you feel pretty nauseous. Some women throw up as labor progresses, even if they haven’t been eating.

10.

Wipe baby’s mouth and nose with a clean cloth. If help hasn’t arrived and the baby isn’t breathing or crying, rub his or her back, keeping the head lower than the feet. If breathing still hasn’t started, clear out the mouth some more with a clean finger, and give two quick and extremely gentle puffs of air into his or her nose and mouth.

11.

Don’t try to pull the placenta out. But if it emerges on its own before emergency assistance arrives, wrap it in towels or newspaper, and keep it elevated above the level of the baby, if possible. There is no need to try to cut the cord.

12.

Keep both mother and baby warm and comfortable until help arrives.

En Route to the Hospital

If you’re in your car and delivery is imminent, pull over to a safe area. If you have a cell phone with you, call for help. If not, turn on your hazard warning lights or turn signal. If someone stops to help, ask him or her to call 911 or the local emergency medical service. If you’re in a cab, ask the driver to radio or use his cell phone to call for help.

If possible, help the mother into the back of the car. Place a coat, jacket, or blanket under her. Then, if help has not arrived, proceed as for a home delivery. As soon as the baby is born, proceed to the nearest hospital.

Whether you can chow down or not during labor, your coach definitely can—and should (you don’t want him weak from hunger when you need him most). Remind him to have a meal before you head off to the hospital or birthing center (his mind’s probably on your belly, not his) and to pack a bunch of snacks to take along so he won’t have to leave your side when his stomach starts growling.

“Is it true that I’ll be hooked up to an IV as soon as I’m admitted into the hospital when I’m in labor?”

That depends a lot on the policies of the hospital you’ll be delivering in. In some hospitals, it’s routine to give all women in labor an IV, a flexible catheter placed in your vein (usually in the back of your hand or lower arm) to drip in fluids and medication. The reason is precautionary—to prevent dehydration, as well as to save a step later on in case an emergency arises that necessitates medication (there’s already a line in place to administer drugs—no extra poking or prodding required). Other hospitals and practitioners omit routine IVs and instead wait until there is a clear need before hooking you up. Check your practitioner’s policy in advance, and if you strongly object to having a routine IV, say so. It may be possible to hold off until the need, if any, comes up.

You’ll definitely get an IV if an epidural is on the agenda. IV fluids are routinely administered before and during the placement of an epidural to reduce the chance of a drop in blood pressure, a common side effect of this pain relief route. The IV also allows for easier administration of Pitocin should labor need to be augmented.

If you end up with a routine IV or an IV with epidural that you were hoping to avoid, you’ll probably find it’s not all that intrusive. The IV is only slightly uncomfortable as the needle is inserted and after that should barely be noticed. When it’s hung on a movable stand, you can take it with you to the bathroom or on a stroll down the hall. If you very strongly don’t want an IV but hospital policy dictates that you receive one, ask your practitioner whether a heparin lock might be an option for you.

With a heparin lock, a catheter is placed in the vein, a drop of the blood-thinning medication heparin is added to prevent clotting, and the catheter is locked off. This option gives the hospital staff access to an open vein should an emergency arise but doesn’t hook you up to an IV pole unnecessarily—a good compromise in certain situations.