What Stays in Vegas (30 page)

Read What Stays in Vegas Online

Authors: Adam Tanner

Gary Loveman embraces tailored cell phone messages based on knowing where you are, provided the marketing does not cross certain boundaries. “For example, when I am carrying this stupid thing around and when I land in Hong Kong I immediately get an offer of different types of services in Hong Kong through SMS [text message]. Usually it's a ferry service or a trip to a sightseeing venue or something like that,” he says. “And the worst case is that you just delete it. I don't think anybody finds that too troubling. And we're not using that to call their spouses and tell them they are in Las Vegas at the moment, which I suspect might be disturbing.”

Yvette Monet, a spokeswoman for MGM Resorts International, says her company does not target based on very precise location, although such ability exists. The casino chain's technology notes what ZIP code users are in, not exactly where they are. Thus it might send an offer to everyone in 89109 around the Strip, not just to people in a rival casino. “We are in the process of expanding our property Wi-Fi

capabilities so that we can send to people within our properties some offers, but we're not there,” she says. “With Wi-Fi, for example, if I go to the swimming pool and then leave the swimming pool to go somewhere else in the hotel, the hotel knows I've been at the pool and they'll send me an offer to lure me back to the pool.” Or perhaps the hotel would send a message about a restaurant special or casino tournament, all aimed at keeping customers engaged and spending at the hotel. Joshua Kanter says Caesars have similar plans and adds that every self-respecting marketing company will do the same.

From a business perspective, knowing more about clients can only help, whether from smart phone GPS information or commercial profiles bought from data brokers. Yet such data gathering raises privacy sensitivities. Unlike the loyalty card data, which customers willingly exchange for rewards, mobile technology allows companies to collect a lot of data about customers without their active knowledge.

Rich Mirman helped fine-tune what was then Harrah's data collection on its clients. But tracking consumer location through mobile phones makes him uneasy. “Now, to me it seems a little bit unethical in terms of watching their movements without them knowing that you are watching their movements,” he says. “There is a big difference in me pulling a card out of my wallet, either handing it to the pit boss, handing it to the waitress, or putting it in the slot machineâthat's a deliberate act that says I want you to know something about me.”

Walter Salmon, the former Harrah's board member who is now in his eighties, also has concerns. He says he'd rather that a competitive company not know the very moment that he is shopping in Best Buy, even if the rival is sending a promotion for a better offer. “I think there is a line there because I think it's disturbing my privacy,” he says. “What if someone went to a house of prostitution?”

As with many areas on the frontier of the business of personal data, Caesars are struggling to find the right mix of advancing their business interests and giving clients something of value in return. “We don't want customers to feel that we are Big Brother, but there is value in having access to that kind of information, so we are trying to find the right balance,” Kanter says. As for Salmon's comment that companies

could know that someone had visited a house of ill repute, Kanter replied curtly: “That would be useless information to us because it is so unrelated to our business.”

Making real-time use of data from clients' smart phones remains difficult, but businesses are moving in that direction. Caesars are now beginning to think about how to collect that data at vast scale and interpret it in real time.

Personalizing the Slot Machine

Some insiders believe that the real long-term problem facing casinos is not marketing but demographics: many people weaned on video games and the Internet are not as interested in today's casino games as their parents or grandparents. Kanter, part of a demographic of players in their thirties and forties vital to the future of casinos, admits it took him a while to understand the appeal of slot machines, the big money makers at American casinos today. When he first started at Caesars he just did not see why anyone liked them. “The odds are against you, you're going to lose, why would you do that stupid thing?” he thought. Then he started playing Slotomania, an online slot game Caesars own and market widely across the Internet, Facebook, and iTunes. He began to appreciate the rhythm: long lulls of losses punctuated by thrills of big wins. “It's restful and entertaining at the same time,” he says. “There is something Zen-like about being there.”

15

Slot developers hope their games of the future will not be an acquired taste but a compelling pleasure. Adding personal data to the mix may help. Patti Hart, CEO at International Game Technology, a leading slot machine manufacturer, says her machines may one day make more use of personal data, welcoming regulars through retinal scans, face or voice recognition, or fingerprints. “I can personalize this slot machine to be the Patti slot machine,” she says. “It has my family pictures, it has my music, it has, you know, my friends and whatever. I can send a Facebook notification to my family that I just won $300 at the Elvis machine.”

“The only impediment for us is not technology; it's regulation.”

Hart says she is sensitive to privacy concerns, although she believes the issue will fade over time. Some people will not want to be tracked, she says, but she expects such sentiment to diminish. “I think the world has moved to a place where people are saying, âI want personalization and in order to get personalization I have to give you data,'” she says.

John Acres, the innovator who devised the first slot player tracking systems in 1983, says slot machines of the future must incorporate far more personal data and involve friends to make them more social. He wants to take data he can instantly glean from third-party sources, such as income level, age, gender, and club memberships, and adapt the machine to suit the player's profile. The overall plan is to change the machine characteristics based on what it perceives about the user.

16

Acres has done well as an entrepreneur over the years. He says he sold his last business for $143 million. His share was about $50 million. He has spent $23 million, about a third of that from his own pocket, in recent years trying to revolutionize casinos. His slot machines of the future would introduce bonus rounds and winnings based on who the player is. So the basic cycle of spins would still have the same odds as before and would not turn a winning spin into a loss. But he would supplement the natural cycle with player-specific bonus winnings built into the natural cycle of the game. “Gary Loveman is going to mail you $100 in free play. So I'm saying, âWhy do we have to pay homage to the postal service? Why don't I just give it to you right here?'” he says. Both cases constitute marketing costs by the casino; Acres thinks his scenario will engage gamblers more.

Authorities would have to change the rules for Acres to realize his vision. He fully realizes he may fall completely flat on his face. “I claim that I can see the future. The difference between being a visionary and being delusional is impossible to tell without seeing how the future unfolds. It could be absolutely delusional,” he says.

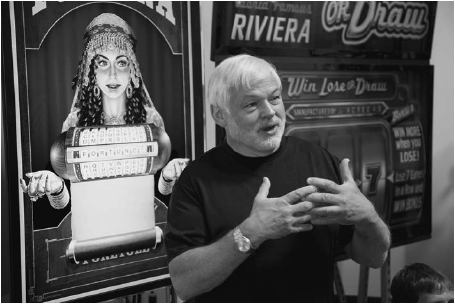

Acres's vision of the future is intriguing. With white hair, white beard, and powerful biceps, he has the aura of a prophetâa data prophet. He wants to learn even more about customers by purchasing large amounts of information from data brokers. Might gathering all that data to operate a casino game appear a bit creepy? “It's

absolutely creepy. It depends on how you use it,” he says. “If I creep you out or discourage you from a relationship with me, I've crossed the line. If I have encouraged you or improved the relationship with me, I haven't. . . . We will never have the anonymity that we once had. That is part of the price of living in modern society. It's not an option,” he continues. “Creepiness changes with time. Over time you will come to accept it. It's not going away.”

John Acres at his Las Vegas office in front of some of his casino innovations, including Madame Fortuna. Source: Author photo.

Casino Adventures in Three Cities

Your Casino Dossier in Real Time

The day before Christmas is another busy day for Tom Cook, manager of Harrah's in North Kansas City. Unlike in Las Vegas, where people journey specifically to gamble, casinos in smaller cities rely on locals to fill the seats at slot machines and gaming tables. Keeping regulars happy is vital to Cook's business on the banks of the Missouri River.

He scoops a smart phone out of his pocket and launches an app called RTCMâreal-time casino marketing. A stream of emails starts arriving, telling him intimate details about his best customers playing at that moment, including exactly where they are sitting scattered among 1,600 slot machines in the cavernous casino.

The first email updates the manager about Richard. The gambler has gathered 165,000 loyalty points for the yearâequivalent to roughly $82,500 in annual spending. He is one of just three hundred or so top-level Seven Stars members in the Kansas City area. Such players make up the top 0.5 percent of gamblers at the world's largest casino company, but they account for $1.3 billion of Caesars Entertainment's more than $8 billion in annual revenue. The company rewards such top-tier members every year with a complimentary dinner worth $500 and a cruise ship voyage, along with access to elite lounges.

On this day so far, Richard has cycled $4,940 through the machines. Since Harrah's Kansas City sets the machine to keep an average of 10 percent of slot bets, he should have lost $494 by now. However, the email tells Cook that as of 12:05 p.m., Richard is down $688. On

his last visit four days before, he lost $1,390. The update also reminds the manager of Richard's birth date and year, and notes he lives in the Kansas City area.

Cook navigates toward Richard between the long banks of slot machines. An orchestra of sound pours forth, a chorus of

ka-ching

and excitement emitting from the bellies of the machines. Themes and catch phrases from old television shows and movies compete for attention. The manager arrives before an unusually complex series of spinning video images called Li'l Red. There he greets a solidly built man sporting a white mustache and a long-sleeve T-shirt. The two chat amiably, although Richard keeps playing most of the time. He says he has lost about $200 so farâa far rosier assessment than his real loss. Cook does not correct him. They trade stories of gym routines, diets, and a new food delivery service. Richard jokes that he likes the Li'l Red machine because the female cartoon character on top has larger-than-average breasts.

Management wants to keep a balance between showing special friendliness to big spenders and not bothering them too often. So after the conversation, the casino manager sends a quick email to the system noting that he has spoken with Richard. The rest of the staff will now wait at least a week before singling him out again for a special greeting. Cook then moves to say hello to Janet, playing at machine CC02. She typically loses $600 a day, but today she is up $286. Her profile also says she has accumulated $455 of freebiesâfor items such as show tickets or meals, to which casino hosts can throw in another $33 at their discretion. By the time he arrives, Janet has moved to machine GD03. Although the machines are all wired, they transmit data on a low-speed network, so it can take a few minutes for the email to arrive in Cook's phone. Another email soon shows her latest location, but by the time Cook arrives she has risen from her seat and is briskly walking away. Rather than stop her midstride, he says nothing.

The next email gives a profile on John at slot machine UB01. He has to accrue just a few thousand more points to remain a Seven Stars elite member for the following year. “I'm sure that's why he's here,” Cook thinks.

When the manager arrives to say hello, John barely glances away from his slot machine. They exchange few words; the manager moves on. Cook knows that many players just want to zone out and escape into their favorite machine. He carefully gauges who is talkative, who loves bawdy jokes, who prefers a quick hello. He knows John is a man of few words, and besides that, he knows John is enjoying a good streak: he is up $59 although the odds suggest he should be down $145 by then. And he is enjoying an especially good day compared to his last outing, five days before, when he lost $772. A three-letter “behavior segment” code in the email also shows that John has been coming less frequently than he had in the past and has been spending less.