West with the Night (34 page)

Read West with the Night Online

Authors: Beryl Markham

Success breeds confidence. But who has a right to confidence except the Gods? I had a following wind, my last tank of petrol was more than three-quarters full, and the world was as bright to me as if it were a new world, never touched. If I had been wiser, I might have known that such moments are, like innocence, short-lived. My engine began to shudder before I saw the land. It died, it spluttered, it started again and limped along. It coughed and spat black exhaust toward the sea.

There are words for everything. There was a word for this — airlock, I thought. This had to be an airlock because there was petrol enough. I thought I might clear it by turning on and turning off all the empty tanks, and so I did that. The handles of the petcocks were sharp little pins of metal, and when I had opened and closed them a dozen times, I saw that my hands were bleeding and that the blood was dropping on my maps and on my clothes, but the effort wasn’t any good. I coasted along on a sick and halting engine. The oil pressure and the oil temperature gauges were normal, the magnetos working, and yet I lost altitude slowly while the realization of failure seeped into my heart. If I made the land, I should have been the first to fly the North Atlantic from England, but from my point of view, from a pilot’s point of view, a forced landing was failure because New York was my goal. If only I could land and then take off, I would make it still … if only, if only …

The engine cuts again, and then catches, and each time it spurts to life I climb as high as I can get, and then it splutters and stops and I glide once more toward the water, to rise again and descend again, like a hunting sea bird.

I find the land. Visibility is perfect now and I see land forty or fifty miles ahead. If I am on my course, that will be Cape Breton. Minute after minute goes by. The minutes almost materialize; they pass before my eyes like links in a long slow-moving chain, and each time the engine cuts, I see a broken link in the chain and catch my breath until it passes.

The land is under me. I snatch my map and stare at it to confirm my whereabouts. I am, even at my present crippled speed, only twelve minutes from Sydney Airport, where I can land for repairs and then go on.

The engine cuts once more and I begin to glide, but now I am not worried; she will start again, as she has done, and I will gain altitude and fly into Sydney.

But she doesn’t start. This time she’s dead as death; the Gull settles earthward and it isn’t any earth I know. It is black earth stuck with boulders and I hang above it, on hope and on a motionless propeller. Only I cannot hang above it long. The earth hurries to meet me, I bank, turn, and sideslip to dodge the boulders, my wheels touch, and I feel them submerge. The nose of the plane is engulfed in mud, and I go forward striking my head on the glass of the cabin front, hearing it shatter, feeling blood pour over my face.

I stumble out of the plane and sink to my knees in muck and stand there foolishly staring, not at the lifeless land, but at my watch.

Twenty-one hours and twenty-five minutes.

Atlantic flight. Abingdon, England, to a nameless swamp — nonstop.

A Cape Breton Islander found me — a fisherman trudging over the bog saw the Gull with her tail in the air and her nose buried, and then he saw me floundering in the embracing soil of his native land. I had been wandering for an hour and the black mud had got up to my waist and the blood from the cut in my head had met the mud halfway.

From a distance, the fisherman directed me with his arms and with shouts toward the firm places in the bog, and for another hour I walked on them and came toward him like a citizen of Hades blinded by the sun, but it wasn’t the sun; I hadn’t slept for forty hours.

He took me to his hut on the edge of the coast and I found that built upon the rocks there was a little cubicle that housed an ancient telephone — put there in case of shipwrecks.

I telephoned to Sydney Airport to say that I was safe and to prevent a needless search being made. On the following morning I did step out of a plane at Floyd Bennett Field and there was a crowd of people still waiting there to greet me, but the plane I stepped from was not the Gull, and for days while I was in New York I kept thinking about that and wishing over and over again that it had been the Gull, until the wish lost its significance, and time moved on, overcoming many things it met on the way.

The Sea Will Take Small Pride

L

IKE ALL OCEANS, THE

Indian Ocean seems never to end, and the ships that sail on it are small and slow. They have no speed, nor any sense of urgency; they do not cross the water, they live on it until the land comes home.

I can’t remember her name any more, but the little freighter I sailed on, from Australia to South Africa, appeared not to move for nearly a month, and during the voyage I sat on the deck and read books, or thought about past things, or talked with the few other dwellers in our bobbing cloister.

I was going back to Africa to see my father, after an interval too long, too crowded, and now complete; it was the end of a phase that I felt had grown and rounded out and tapered to its full design, inevitably, like a leaf. I might have started from any place on the earth, I thought, from whatever point — but in the end I should still have been there, on that toy boat, measuring the time.

I carried with me the paper treasure I had gathered — cablegrams about my Atlantic flight from everywhere, a few newspaper clippings culled out of many, a picture of the Vega Gull, nose down in the Nova Scotia bog — and some of the things that had been written about Tom.

Tom was dead. He had been killed at the controls of his plane, and I had got the news a long time ago in New York. It had been telephoned to me from London while I sat, still dazed, in the midst of ringing bells and telegrams and eager people telling me what a fine thing I had done to have almost made Floyd Bennett Field — and would I sign an autograph? There was even a letter in my file, purporting to have been written by a dog, signed ‘Jojo.’ I was deeply grateful for the warmth and unending kindness of America, but I had no complaint about the transitory nature of my fame.

Tom had been killed simply, and avoidably — on the ground. While he was taxi-ing to a take-off position on the Liverpool Aerodrome, an incoming plane had struck his plane, and that was all. No one else had been injured, but Tom had been killed. I suppose it was no more than chance that he had died with the blade of a propeller buried under his heart.

The Gull too was dead. I had been unable to buy her after my flight, and so J. C. had shipped her to Seramai and sold her to a wealthy Indian who might have understood many things, but not the beauty, nor the needs, of a plane. He left her exposed to the weather on the airport at Dar es Salaam until her engine rusted and her wings peeled and she was forgotten by everyone, I think, except myself. Perhaps, by now, some official with an eye for immaculacy, has had her skeleton dragged to the sea and buried in it, but the sea will take small pride in that. The Gull had not failed me. When she was checked, after my flight, it was learned that somewhere off the coast of Newfoundland ice had lodged in the air intake of the last petrol tank, partially choking fuel flow to the carburetor. I had wondered since how, so handicapped, the Gull had flown so long.

All this had happened, and if some of it was hard for me to believe, I had my logbooks and my pound of scraps and papers to prove it to myself — memory in ink. It was only needed that someone should say, ‘You ought to write about it, you know. You really ought!’

And so the little freighter sat upon the sea, and, though Africa came closer day by day, the freighter never moved. She was old and weather-weary, and she had learned to let the world come round to her.

Markham in 1931, shortly after she learned to fly.

“We began every morning at that same hour, using what we were pleased to call the Nairobi Aerodrome, climbing away from it with decisive clamour, while the burghers of the town twitched in their beds and dreamed perhaps of all unpleasant things that drone—of wings and strings, and corridors in Bedlam.”

Margaret Elkington and her mother, “Mrs. Jim” Elkington, with Paddy, the pet lion who attacked Markham when she was a child.

“So Paddy ate, slept, and roared, and perhaps he sometimes dreamed, but he never left Elkington’s. He was a tame lion, Paddy was. He was deaf to the call of the wild.”

C. B. Clutterbuck, Markham’s father. She kept this photograph (inscribed “Daddy, 1946”) by her side throughout her life.

“My father was, and is, a law-abiding citizen of the realm, but if ever he wanders off the path of righteousness, it will not be gold or silver that enticed him, but, more likely, I think, the irresistible contours of a fine but elusive horse.”

The house in Njoro, Kenya, that Markham’s father built when she was fourteen.

“The farm at Njoro was endless, but it was no farm at all until my father made it . . . He was no farmer. He bought the land because it was cheap and fertile, and because East Africa was new and you could feel the future of it under your feet.”

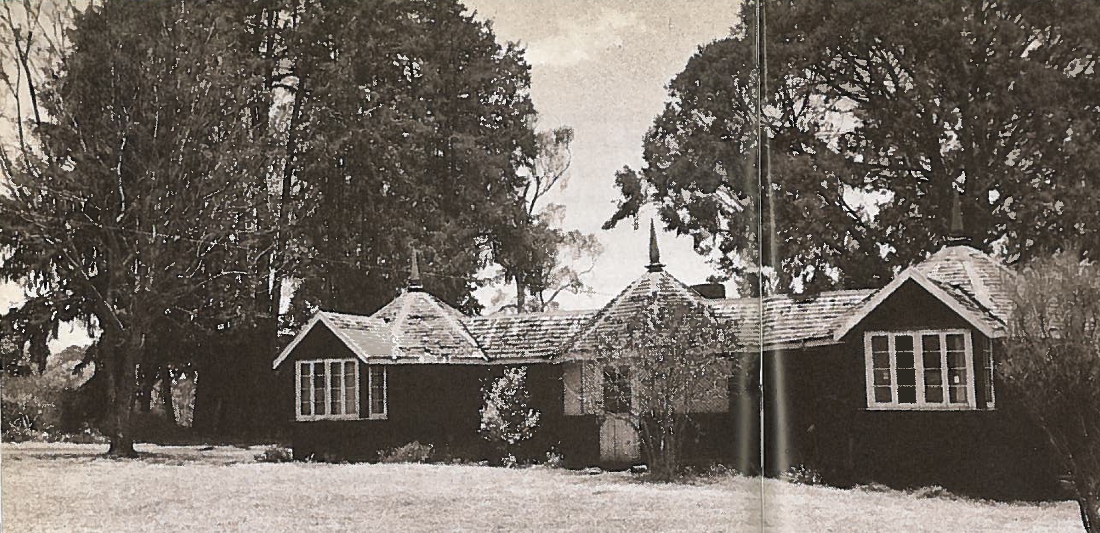

The house where Markham stayed when she returned to Kenya in 1948.

“‘The world is a big place,’ he said . . . ‘But everywhere a man goes there is still more of the world at his shoulder, or behind his back, or in front of his eyes, so that it is useless to go on.’”