West of Here (60 page)

And Jared really was proud, profusely and unexpectedly. So much so, that for a brief moment, looking out over the colorful wash of people toward the lip of the dam, he felt himself misting over. Center stage and three rows deep in the assembly, pressed between a fat lady in an Old Navy sweatshirt and skinny guy in a Stihl chainsaw cap, Krig, too, swelled with pride for J-man.

“Proud not only,” Jared continued, “to be commemorating our long and rich history but to usher in a whole new chapter in our history — the Elwha River Restoration. The inconceivable has come to pass, the dam is coming down, slowly but surely. And I know everyone isn’t happy about it. We’ve been hanging our hat on this dam for over a hundred years.”

A smattering of applause mixed with a few boos rose from the crowd, and when it died back down the hum of the turbines filled the ensuing silence.

“I think it’s important to remember, Port Bonitans, that we have a long history of overcoming adversity, stretching all the way back to the Bucket Brigades of 1890.”

“Hell yes!” Jared heard someone yell. He thought it sounded like Krig.

“And I might add that most of those men and women who fought to save Port Bonita the first time may not have dams and mills and streets named after them, but they’re every bit as much a part of the fabric of our history as the captains of industry.”

Meriwether, near the back of the assembly, could feel the first raindrops on the brim of his white cowboy hat, and he nudged Curtis with an elbow.

Krig felt the first drops on his bare forearm.

Jared could hear the rain tapping on the canopy high above his head.

As the showers came harder, Rita’s cotton candy began to wilt.

Hillary and her mother began making their way to the car.

Jared forged ahead as the crowd began to disperse. “Once again, Port Bonitans, we’ve been presented with the opportunity to rewrite our history.”

“Hell yes!” yelled Krig, determined to stick it out until the very end, even as puddles formed around him and the vendors began closing their hatches, and the band huddled beneath the canopy at the back of the stage. “Tell it like it is, J-man!”

Looking across the vacant muddy flat, Krig noticed that Jerry Rhinehalter had stuck it out, too, leaning against a light standard at the very edge of what used to be the crowd, cupping his cigarette from the rain. His kids were nowhere to be seen.

“For as long as anybody can remember, this dam has been the heart and soul of Port Bonita. It was the Thornburgh Dam that put us on the map, that brought light to our fledgling town, the Thornburgh Dam that powered the mills that fueled our economy for a hundred years. And even as the twentieth century passed it by, the dam remained an unshakable part of our identity. And with the dawn of a new century, the debate surrounding this dam remained at the forefront of our consciousness as a town and, ironically, put us on the map all over again. But” — here J-man paused for dramatic effect — “sometimes we must leave part of ourselves behind in order to move on. And for Port Bonita that means the Thornburgh Dam. But as my great grandfather Ethan Thornburgh said on christening this dam —even as Port Bonita was rising again from the ashes: Port Bonita is not a place, but a spirit, an essence, a pulse; a future still unfolding. So I say to you, Port Bonita: Onward! There

is

a future, and it begins right now.”

WHEN THE RAIN

started falling in torrents, Timmon and Franklin aborted their search for ribs and commenced searching for the Taurus among the sea of automobiles. Up and down three aisles they searched the slab until at last Franklin spotted it, a sopping, inkmottled parking infraction adorning its windshield. Franklin peeled the pink ticket off disgustedly, then fished the keys from his pocket.

Timmon stood at the passenger door, waiting impatiently for Franklin to unlock the car. Tossing his sodden gym bag heavily in the back-seat, Franklin climbed behind the wheel and slapped the ticket on the dash, where it clung like a slice of baloney. He reached across and unlocked the passenger door.

Timmon climbed in and fastened his seat belt. “Better pay that,” he said, registering Franklin’s disgust. “It’s the little shit that will catch up with you if you’re not careful.”

LINGERING AT THE

edge of the gorge, Krig let the rain wash over him, feeling strangely as though he’d lived this moment before. Working the fingers of his left hand over the raw knuckle, then over the pale and unfamiliar flesh the ring had covered for twenty-two years, he wondered how long the imprint would last, whether the hair would grow back on his knuckle, whether the P.B. Varsity Boys would ever make it back to state. If they did, Krig hoped they won it all, even if it meant Port Bonita forgot all about that ’84 squad. P.B. could use a champion. Crossing the muddy clearing, Krig discovered that already the rain was washing away his footprints.

Wending his way through the muddy fairgrounds past the first-aid station and the Speed Pitch, Krig arrived at the north entrance. It was tough not to feel a little wistful stepping over the rope. How many summers had Krig left behind with this very step? How many autumns has he ushered in? Was this the last?

In the distance, Krig saw J-man and Janis climbing into their Lexus. He could see the stain on Janis’s ass from fifty yards. He saw Jerry Rhinehalter two cars in front of J-man, the old station wagon riding low under the massive weight of the Rhinehalter brood. The windows were fogging up in back. In the adjacent row, Krig spotted the Monte Carlo nosing into traffic and felt a bittersweet pang to see Curtis smiling in the passenger seat. Rita had wrestled her wet hair into a ponytail, and Krig thought he knew exactly how it would smell with his lips pressed softly against the nape of her neck.

But there were too many ifs. Too many buts. Too much waiting

around. For the first time in his life, Krig felt that he couldn’t afford to drive in circles anymore; even at forty-two grand a year, he’d still be repeating himself. Even if golfing with Don Buford might be better than watching the Raiders by himself on Sunday afternoons. Even if Rita might change her mind, eventually. J-man had it right: sometimes you gotta leave a part of yourself behind in order to move on. And though he was resolved to his new course of action, intent upon his unfolding future, Krig ached all the more for the past, for the familiarity and convenience and timeless consolation of Port Bonita. And more than ever, he ached to possess Rita, as he watched her inch herself into the fray, as one by one, they all inched themselves into the fray and wound their way down the mountain toward home.

January 14, 2007

Dear J-man,

Aberdeen is cool, but it ain’t P.B. I miss the mountains, the weather kind of sucks, and nobody has Kilt Lifter on tap. But the truth is, I’m not drinking as much these days, anyway — and I stopped smoking weed altogether. It’s funny how much more time I spend looking forward now than back. Most nights I just stay home and read if I don’t have practice. I started coaching Pee-Wee hoops in November. We’re in last place, but since we switched from man-up to a zone, we’re 3–0, and I think we’re just hitting our stride. The kids are really excited. Funny, I didn’t even know I liked kids.

Bad news of sorts: the Goat finally gave up the ghost a couple of weeks ago. The block is shot. Hated to see her go, but I got two grand for the body, and at least I managed to save the furry dash cover — why, I don’t know. I drive a little Geo Metro now, and I’m actually okay with that, even if it’s not exactly a chick magnet. In some ways, it beats that old gas hog.

Thanks for the Christmas card, and congrats again on the baby! He looks just like you! Say hi to the gang at High Tide — and tell Hoffstetter he still owes me twenty bucks for that AFC Championship game. And if you happen to see Rita around, tell her I said “Hey.”

Take ’er easy,

Krig

P.S. I read on the SFRO database yesterday that a guy reported a couple of class B sightings behind his cabin last week, out near Lost Creek, which is in the hills just west of here. I know you think I’m crazy, but I still want to believe. I’m thinking of heading out that way.

I owe a great debt to many sources, texts, and individuals, without whom this book would not exist. If I’ve forgotten to list anybody here, let it be a testament to the scope of my debt.

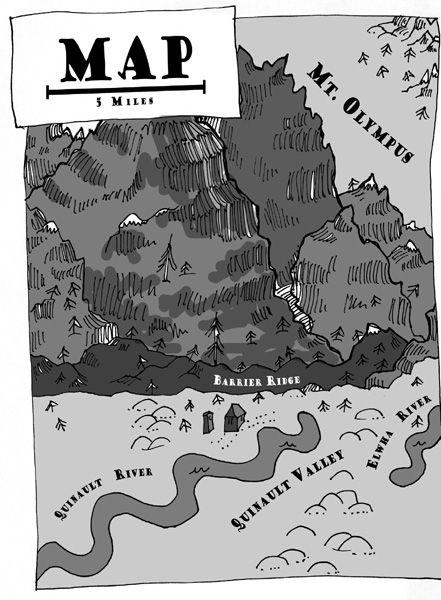

First, Nick Belardes for his super-cool maps; Michael O’Conner for his killer cartoons, though they didn’t quite work, to no fault of his own; and also Shannon Gentry for her work on the early maps.

My wife, Lauren, gets her own line for the patience and diligence it takes to survive a novelist (even on a good day).

Though

West of Here

is very much a work of fiction, much of the “historical” material was inspired by my eighteen months of research, which owes a huge debt to many sources. Robert L. Wood’s wonderful treatment of the Press expedition in

Across the Olympic Mountains, The Press Expedition, 1889–90,

was nothing short of indispensable to my research (not to mention a great read), as well as James H. Christie’s original account of the Press expedition from the

Seattle Press

(July 16, 1890), and Charles A. Barnes’s narrative account of said expedition. Also indespensible to my research was Thomas Aldwell’s

Conquering the Last Frontier,

Paul J. Martin’s

Port Angeles, Washington: A History,

along with

Shadows of Our Ancestors, Readings in the History of Klallam–White Relations,

edited by Jerry Gorsoline, with contributors Lewis L. Langness, Joyce Mordon, Kent D. Richards, Peter Simpson, and Marian Taylor. William W. Elmendorf’s

Twana Narratives

was another invaluable resource, and James G. McCurdy’s

By Juan de Fuca’s Strait

another. Also, Philip Johnson’s

Historic Assessment of Elwha River Fisheries

was extremely helpful, and thanks to Steve Todd for tracking it down for me.

Watershed: The Undamming of America,

by Elizabeth Grossman, was another great resource. An acknowledgment is also due to Murray Morgan, who has contributed so very much toward preserving Washington state’s rich history, which I have so thoroughly turned on its ear herein. A thin book this would be without the wealth of knowledge and insight provided by all of the aforementioned texts.

I would also like to acknowledge the entire staff of the North Olympic and Bainbridge Island Libraries, the Klallam Tribal Center, the Jamestown Tribal Center, Port Angeles Seafood, the Bushwhacker, the Klallam County Historical Society, Olympic National Park, and the guy who invented beer.

Also, a huge thanks to the following individuals for their editorial and critical insight: Mark Boquist (and Pete Droge and Dave Ellis and Sean Mugrage, too) for first coming up with the title

West of Here

with the 1990

Ramadillo release of the same name. Thanks are due to David Rogers, Michael Meachen, Hugh Schulze, Shelby Rogers, David Liss, Margaret Walsh, Gina Rho, and Matthew Comito for their invaluable readings of the manuscript at various early stages and also to Jerry Brady for his inspiring tales of towniehood in Bowie, Maryland (and for the name Krig), Jessica Regel, Jackie Luskey, Stephanie Adou, Ian Dlrymple, Richard Nash, Mom, Dad, Jim, Jan, Davey, Dan, my nephews (Bob, Buddy, Danny, Matthew), my niece (Angie), Carl (you are dearly missed), Lydia, Tup, Brooks, Justin, Tomasovich, my blogging compadres J.R., D.H., J.C., and the rest of my trusty companions, as well as all my brilliant, colorful, and inspiring comrades from the Fiction Files.

A huge thanks to my brilliant editor and advocate Chuck Adams, who pushed me to do my best work at every juncture. Also, big thanks to Elisabeth Scharlatt, Ina Stern, Craig Popelars, Michael Taeckens, Jude Grant, Brunson Hoole, Katie Ford, Michael Rockliff, and everyone top to bottom at Algonquin. And lastly, my friend, agent, and trusted reader, Mollie Glick.