Weird Tales volume 24 number 03 (8 page)

Read Weird Tales volume 24 number 03 Online

Authors: 1888-1940 Farnsworth Wright

Tags: #pulp; pulps; pulp magazine; horror; fantasy; weird fiction; weird tales

Mrs. Van Orton has a figure that looks well m anything, but its effectiveness increases in inverse ratio with the amount of clothing she wears; hence, to some extent, Venice and the Lido. When she walks along the beach, this summer, the women will turn away and the men will turn toward her. The women will say, "Who is that doll-faced American in the daring bathing-costume?" The men are discreet on the Lido—they will say nothing. But they will look.

And spring has come to Washington . Square. The old trees are beginning to think about their Easter clothing. Probably they will decide that the well-dressed tree will wear a very light and delicate chartreuse. Feathers, too, may be worn.

Michael Bonze looked up from his painting. "Darling," he said, "you're the best work I've ever done. And you're just about finished."

"Thank goodness!" said Gilda Ran-some. "May I move, now?"

"Go ahead," he said. "Get up and we'll make some coffee."

He put down his palette and brushes

and helped her into her kimono, kissing, as he did so, the back of her neck.

"I wonder," he said, "if I could have done such a good portrait if I hadn't fallen in love with you. I owe a lot to old Van Orton. If it hadn't been for him—and for Pierre Vanneau "

"Why Pierre Vanneau?" she asked.

Michael smiled in memory of his annoyance. "It was he who first suggested that I paint beautiful women. I was furious."

"So shall I be," said Gilda, "if you dare to paint any woman but me."

"Never fear!" he laughed. "There will be no one but you. I'll paint you as everything from Medusa to the Virgin Mary."

"I might make a Medusa," said Gilda.

Later in the day, the picture was finished to the immense satisfaction of both artist and model.

The next morning Michael arose before Gilda was awake. He wanted to look at the portrait in the cold light of dawn. Without, he told himself, undue self-praise, he found it good—very good. Maybe it wasn't modern, maybe the style wasn't original, perhaps it wasn't spontaneous. But the draftsmanship, the color, the texture, the composition—that was all perfect. ,No one could deny it. It would take no violent stretch of the imagination to conceive the beautiful creature rising from her couch and stepping lightly down from the canvas to the floor.

Bonze thought it wasn't fair that this, his best work, was destined to be hung in a dark, lonely house, among a lot of gloomy Flemish paintings, for the exclusive pleasure of a solitary old Dutchman. After all, Art was for the masses. If Meyergold could see this, he'd sing a different tune. If it weren't for the money. he'd never let Van Orton have the picture

NAKED LADY

323

—the insulting old idiot! He wouldn't appreciate it, anyway. It wouldn't have made any difference to him if the picture had been good or bad. All he wanted was a likeness.

On the heels of this reflection, Bonze realized in a flash of inspiration how he could keep his picture. He would make a copy and give that to Van Orton. Naturally, it wouldn't be so good as the original, but what of that? He hadn't promised to deliver a masterpiece. Of course, there was the matter of those little packets of powder—he'd used it all in the original—but—well, it was silly, anyway.

He woke Gilda with a shout and told her his plan. "I'll have the thing finished by the end of the week. Then I'll get my check and we'll go right down to the City Hall and be married."

Gilda looked at the clock on the bed table. "Is this a nice hour to propose to a girl?" she groaned and pulled the covers over her head.

Whistling loudly and cheerfully, Michael started to work.

Jeremiah van orton crouched before the likeness of his wife lying nude upon a chaise-longue. He had never seen her so. She had always kept him at arm's length. But now she was near—near enough to touch with the finger tips, or a long pin, or a keen-edged knife.

Though never for a moment did he take his mad gaze from the portrait, he did not neglect the task at which he worked. Methodically, he sharpened on a whetstone a number of efficient-looking probes and knives. The scrape of the steel and his panting breath v/ere the only sounds in the darkened room. Incessantly, he moistened his opened lips with his tongue. His heart pounded in his ears.

Jeremiah knew that the excitement of

the execution was killing him, that he must hurry. He got to his feet and addressed the painting in a high, cracked voice.

"Marion," he said, "I hold your life in this image by virtue of your skin and blood. Do you understand? This is you!"

He tried the point of a blue steel probe against his thumb. His voice rose to a shriek.

"You are going to die, Marion, my love, wherever you are!"

His bloodshot eyes fixed themselves in a hypnotic stare as he approached the portrait. Great veins throbbed in his shriveled neck and temples.

"TT^xcellent!" said Mr. Meyergold. Xl/ "Really excellent! I must say, my dear Bonze, you surprize me!"

He looked around with an expression frequently worn by owners of dogs that are able to sit up or shake hands. He assumed an air of patronizing pride. He reasoned that he had played an important part in the development of this young artist by his stern and uncompromising rejection, until now, of everything he had done. He turned again to the picture and nodded. Bonze was a good dog and it was no more than fair to throw him a bone—he had earned it. "Excellent!" he repeated. "What do you call it?"

"I call it," said Michael, racking his brain for a likely name, "I call it 'Naked Lady."

Mr. Meyergold glanced up sharply. "Naked Lady." He rolled it around on his tongue. "Good! Oh, very good! A fine distinction. This is no ordinary nude; no allegorical Grecian goddess to whom a yard of drapery more or less makes no difference." He thought that an awfully good line for a review and decided to make a note of it the instant

WEIRD TALES

he left. He laughed in appreciation of his wit. "Oh, no, this young lady is shy and embarrassed without her clothing." He went on enlarging the idea in the hope that he would hit upon another useful line. "Here you've caught a lady in a most undignified situation. I get the impression that your 'Naked Lady' is very much annoyed with us for looking at her."

IN her cabin on the beach, Marion Van Orton was changing from her bathing-suit to an elaborate pair of pajamas. Suddenly she had a distinct impression that she was being observed. She jerked a bath-towel up to her chest and swung around. Apparently there was nothing to account for her fear. But she knew that someone was minutely examining her. Hurriedly, she pulled on her pajamas and ran from the cabin, fully expecting to surprize some rude man in the act of staring through a chink in the wall. There was no one near.

In spite of the heat of the day, she went back-into the cabin and wrapped a heavy cloak tightly about her. Still the miserable feeling persisted.

"My goodness!" she said to herself, "I feel positively naked!"

A month later, Marion Van Orton had - cause to remember that day on the Lido. She was sitting in the Excelsior Bar, reading a New York Times, two weeks old. She had really been looking through it to see if there were any more news of the death of her husband. For a few days the papers had been full of "Millionaire Husband of Actress Found Dead." When she had first heard of it she had wondered which of the paintings

it was that had been found slashed to rags and tatters, and she wondered what had happened before his heart failed that had made him want to ruin one of the pictures of which he had always been so proud.

There was nothing more in the Times. The story had been squeezed dry and dropped in favor of an expedition to the South Pole. Finishing a rather dull announcement of the forthcoming exhibit of paintings by an artist who had just married his model, Marion turned to her handsome companion.

"Some people insist," she said, "that more important things happen in New York than here, or anywhere else. But look at this paper; there isn't an interesting or important thing in it. It's all too, too boring for words."

And then, quite suddenly, that awful nightmarish feeling returned to her. She was entirely naked and people were looking at her, criticizing her, appraising her. As she crossed her arms at her throat, here eyes darted about the room, searching for the guilty Peeping Tom. She could detect no one, but she knew, she knew that to someone her clothing was perfectly transparent.

Without excusing herself to her startled friend, Mrs. Van Orton jumped up and rushed to her room in the hotel. She locked and bolted the door. The sensation was growing stronger every moment. She pulled down the shades and turned off the light. But it was no better. She ran into the clothes closet and shut the door. Even there, there was no escape from the certain knowledge that she was bare and defenseless before a crowd. She drew the hanging dresses tightly around her and shrank into a corner of the closet. She felt she was going mad.

(2/inister Pamtinj

By GREYE LA SPINA

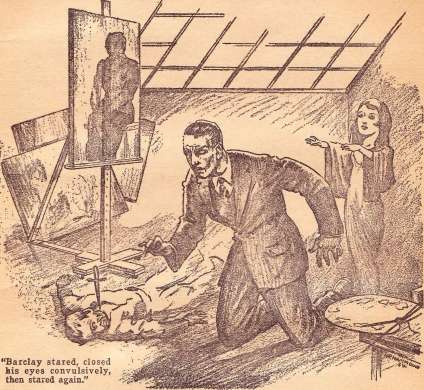

•'Barclay stared, closed his eyes convulsively, then stared again."

An eery story of a fiendish murder and a midget psychic investigator — by the author of "Invaders From the Dark" and "The Devil's Pool"

THE taxi drove off, leaving Funk on the Hoddeston lawn, surrounded by valises. Funk was thinking it more than merely odd that Barclay, for whose coaching he had come prepared to spend a month, had not met him as planned. He tried the screen door; it was hooked inside.

"Hello, in there!" he hailed hopefully. There was no response. The Hoddes-

ton farm lay drenched in a torpid lethargy for which it was obvious more than the July heat must be responsible. Within the house, no one stirred. On the surrounding fields, no one was abroad. Even the usual sounds of the farm animals were hushed.

Funk was unpleasantly affected. Surely the entire household had not gone to meet his train and somehow missed it.

WEIRD TALES

He carried his traps to the stoop, crossed the yard to the barnyard, and halloed again. He knew of old where Barclay's studio was, so he set off down the path toward the grateful shade of the woods.

The gray stone walls of the old building soon glinted through the tree trunks and heavy foliage. A strong conviction possessed Funk that Barclay was not within. In fact, he found the studio door padlocked. He noted that the west window was rudely boarded up. He walked around the studio to the north.

Here the trees had been cut down, and the studio wall was entirely of glass. He peered in with deepening curiosity, but apart from the usual litter of easels, painting paraphernalia and accessories, canvases in serried rows against the walls, his attention was almost immediately drawn to a painting propped against the south wall where the full light from the opposite windows poured in revealingly.

"Rum go!" Funk muttered, puzzled. "That never is Barclay's work. And he would never have let a student perpetrate such a monstrosity of line and crude color."

He pressed his face to the glass, cupping it against the outside light.

"That old man," Funk said aloud, amazed, "may be crudely done, but he's also absolutely horrible. His hands— ugh, they're dead hands. Bloodless— waxen—aaarrrgh! Something about the way he's sitting there—drooping as if he hadn't the strength of himself to sit erect, and was being held by something—something without, that you can't see. ... I don't like the thing. It's ugly. There's —something wrong with it."

He said this last with conviction, and as he exclaimed became aware of another gaze fixed upon himself. He snapped upright and wheeled quickly. Waiting

patiently for him to finish his examination of the studio's interior stood a man in patched, stained blue overalls.

"Well?" snapped Funk sharply, a bit taken aback.

"Mr. Barclay's at the house, sor. You're Mr. Funk? I'm Mulcahy, Hoddeston's hired man."

Funk nodded. "All right. I'm coming. How did Mr. Barclay come to miss my train?"

"We was all down to the police station, sor." Mulcahy fell in behind him.

"Police station?" echoed Funk. "What's been going on here?"

"I found Mr. Oakey dead in the studio this mornin', sor."

"What!" Funk whirled and confronted the Irishman.

"There's somethin' wrong in there, sor. I saw blood on the ould divil's beard." The man's voice quavered.

"Snap out of it, Mulcahy. Are you referring to that—picture?"

"I am that, sor." .

"Blood on the old man's beard? Ridiculous! I saw none."

Mulcahy insisted stubbornly: "Blood it was, sor. An' the poor young man's was all drained out av him, sor."

Funk stiffened to deep attention. "Ha! This sounds intriguing. Blood on the old man's beard?"

"An' drippin' from his dead fingers, sor. An' not wan dhrop left in the corpse, sor. Blood—all over the dommed ould divil's whiskers, an' his dead fingers, sor. Mary Mother!" Mulcahy crossed himself with pious haste.

"Who did that painting?" Funk demanded, turning again toward the house.

"A mon be the name av Silva, sor. He's afther bein' a cabinet-maker, but he got to thinkin' he cud paint, so he made that beauty back there, divil fly away wid him!"