We Two: Victoria and Albert (16 page)

Read We Two: Victoria and Albert Online

Authors: Gillian Gill

When the Queen drove out in state to open parliament for the first time, ordinary folk lined the streets to catch a glimpse of her. The assembled lords and commons listened reverently as the tiny young woman in her ermine and diamonds, now romantically slender and pale after her long ordeal, gave the speech from the throne without a waver. When the Queen held her

first official assemblies for male visitors, called levees, English notables and foreign diplomats attended in droves. In her journal Victoria proudly recorded that in one session three thousand men kissed her hand.

When the Queen announced that she intended to review the Household Cavalry on horseback as the young Queen Elizabeth had done, her mother was appalled, and the Duke of Wellington strongly advised against it. I know horses, pontificated the hero of Talavera and Waterloo, and no horse can be trusted to behave at a military parade with a woman in the saddle. But Victoria was not to be dissuaded. Perched sidesaddle on her great horse Leopold, dressed in a modified version of the Windsor uniform, the Star of the Order of the Garter on her breast, the Queen cantered up the lines and saluted the troops in perfect form. The massed bands played, the pride of England’s army fired and skirmished and dashed feverishly to and fro, but the Queen had her horse under complete control. “I felt for the first time like a man, as if I could fight myself at the head of my troops,” the Queen confided to her diary.

Victoria’s coronation in June 1838 cost only seventy thousand pounds, a fraction of her uncle George IV’s, but it was greeted with general rejoicing. The unprecedented crowds of people massed all along her route to and from Westminster Abbey made the Queen feel both proud and humble. When the crown was placed on her head, the Queen looked up into the gallery where her dearest friend, Baroness Lehzen, was sitting, and the two exchanged a smile. Together they had come through, and the victory was theirs. The Queen also found the presence of Lord Melbourne at her shoulder an immense comfort, although she worried that the ordeal of bearing the massive sword of state aloft during the processions would be too much for him. Suffering from an intestinal disorder, Melbourne had taken opium and brandy.

The coronation was a triumph for the young Queen, though not for the old men in charge of the arrangements. Both the Earl Marshall and the Archbishop of Canterbury had forgotten exactly what order the complicated ceremony should follow, didn’t bother to look it up, and didn’t believe in rehearsals. Rather to the Queen’s surprise, wine and sandwiches were laid out on the altar of a side chapel for the principal performers, but apart from that, nothing much got organized. At the Queen’s insistence, the massive state crown was made smaller and lighter to fit her head. She still got a headache when wearing it, but at least when peers lurched forward to touch the crown in their ritual sign of allegiance, they did not dislodge it from her head. When one old nobleman toppled backward down the stairs leading to the throne, the Queen charmingly came forward to offer him her

hand. When the archbishop insisted on jamming onto her fourth finger the coronation ring that had been made for the pinky, she did not shriek or faint. The weighty orb and scepter were put into her hands far too early but she managed not to drop them. She processed into and out of the abbey with grace and dignity despite the eight young lady trainbearers who kept getting their feet caught in their own trains.

When night fell, Victoria repaired to the Duchess of Kent’s rooms at the far side of Buckingham Palace, not because she wished to talk over the events of that extraordinary day with her mother but to get a better view of the fireworks. The Queen assured Lord Melbourne that she was not at all tired, and she wrote in her diary a long, detailed monarch’s-eye view of the coronation that is one of the most delightful documents in Victorian letters.

Charles Greville, the recording secretary to the Privy Council, who saw a good deal of Victoria in the months after her accession, noted in his diary how very much she was enjoying being Queen. “Everything is new and delightful to her. She is surrounded with the most exciting and interesting enjoyments; her occupations, her pleasures, her business, her Court, all present an unceasing round of gratifications. With all her prudence and discretion she has great animal spirits, and enters into the magnificent novelties of her position with the zest and curiosity of a child.”

Though assailed by new challenges at every turn, Victoria felt happier and healthier than ever in her life before. To her half sister, Feodora, in Germany, she wrote on October 23, 1837: “I am quite another person since I came to the throne. I look and am so well. I have such a pleasant life, just the sort of life I like. I have a great deal of business to do, and all that does me a world of good.” To her uncle King Leopold of the Belgians, she wrote how much she liked and trusted Lord Melbourne, adding: “I have seen almost all of my other Ministers, and do regular, hard, but to me

delightful

, work with them. It is to me the

greatest pleasure

to do my duty for my country and my people, and no fatigue, however great, will be burdensome to me if it is for the welfare of the nation.”

Over the years, Leopold and Baron Stockmar had received extravagant expressions of girlish affection from Victoria, and they assumed that she would take her cues from them, especially in foreign policy. They soon learned their mistake. The new Queen was ready to take advice but had no intention of being anyone’s puppet. When she smelled condescension or manipulation even from “Dearest Uncle,” she said no with gracious aplomb. Once Victoria had been lonely and snubbed, but now, with such seasoned and deferential statesmen as Lord Melbourne and Lord Palmerston constantly at her elbow, she felt more than ready to take on the worlds

of domestic politics and international diplomacy. The Queen not only held cabinet meetings with her ministers, she rode out in the afternoons with them on twenty-five-mile adventures that took her out of London, chatted vivaciously with them over dinner, and played her favorite parlor games with them.

IN HER PERSONAL

finances, Queen Victoria was determined from the beginning not to repeat the mistakes of her uncle George IV. The Queen was not the richest woman in England. That honor belonged to Angela Burdett-Coutts, a multimillionairess who inherited the Coutts banking fortune from her mother. A number of Englishmen—the dukes of Devonshire and Westminster, to name only the most prominent—were many times richer than the Queen. Nonetheless, Victoria was a very wealthy woman, and, having escaped the greedy clutches of Sir John Conroy, she took on the management of her own money.

This was unusual. Law and custom increasingly excluded English women from the world of business. Having no head for figures was considered an asset in the female citizen. But Victoria had inherited some financial

acumen from her paternal grandfather, George III, and her maternal grandmother, Duchess Augusta of Coburg. She was good at figures and diligent with paperwork. She had an exceptional memory; she was a shrewd judge of men even as a raw girl; she knew how to delegate; and she had an associate she trusted. Prime Minister Lord Melbourne offered advice to Her Majesty on her personal affairs when he was asked, but Victoria mainly relied on “dearest Daisy”—that is to say her former governess, Baroness Louise Lehzen. The lady in attendance on the Queen served not only as secretary in private correspondence, but also unofficially as the comptroller of Her Majesty’s household.

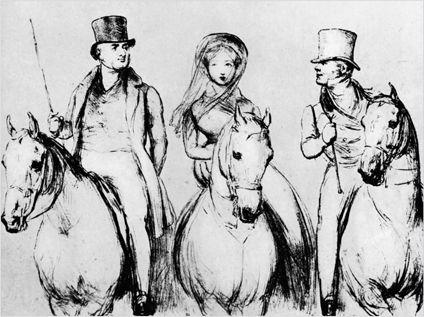

Queen Victoria riding out between Lord Melbourne and Lord John Russell

In money matters, as in so much else, Louise Lehzen had an admirable influence on the young Victoria. Forced to work for her living since girlhood, paid a miserable wage by her employer, the Duchess of Kent, Lehzen had always been frugal, but she had her own code of honor. She was honest in her dealings, and she did not prize money and possessions for themselves. Even when Victoria became Queen, the baroness made no demands for status or fortune: for her it was enough to be an acknowledged power behind the throne and to live constantly in her darling’s company. Unlike Sir John Conroy and his cronies during Victoria’s minority, Lehzen has never been charged with keeping false accounts or misappropriating funds.

Lehzen understood basic economic precepts: live within one’s income, keep an eye on the servants but pay their wages, check the tradesmen’s bills but settle them quickly, add up the pounds, shillings, and pence every month. These were things Victoria’s profligate German mother and debt-ridden English uncles could not teach her. The princess had a fierce love of honesty and truth and she loved and respected her governess; so the lessons fell on fertile soil.

In the days immediately after her accession, Victoria found herself very uncomfortably placed. Her mother had never allowed her any discretionary money, and the new Queen now found herself with vastly increased expenses, and her income from parliament had yet to be voted through. Coutts the banker obligingly loaned the Queen the money she needed to tide her over, and was both surprised and gratified when she paid it back as soon as her income from the civil list began to flow into her pocket.

Victoria than allocated fifty thousand pounds from her first year’s privy purse to pay the debts that her father had contracted before her birth, which her mother had left outstanding. When the Duchess of Kent told people that she was responsible for the debt repayment, Victoria was privately furious but publicly silent. She sent some welcome money to poor relatives,

notably her half sister, Feodora. She paid her personal servants generous wages and was a sympathetic and considerate mistress. She took time out of a busy life to scrutinize her milliner’s bills.

Given their lack of experience in the world of business, and the complexity of the royal financial situation, Victoria and Lehzen together did an honorable and competent job. They had a sense of fiscal responsibility and a horror of debt. This in itself was a revolution in royal affairs.

IN HER SOCIAL LIFE

, Queen Victoria kept close to the staid and virtuous model developed by her grandfather George III in his first years on the throne. She found her friends among the high aristocracy, as English kings always had, she took people very much as she found them, and had a strong appetite for fun, but she showed none of George IV’s precocious taste for vice.

During the period between Victoria’s accession and her marriage, Prime Minister Lord Melbourne was indisputably the person closest to the Queen. Such a close rapport between a monarch and a prime minister was not unprecedented, but it was rare. Melbourne saw the Queen almost every day, often several times a day at her urgent request, and there was a room reserved for him at Windsor Castle. Melbourne saw Victoria far more often and more often alone than did the Duchess of Kent, who, when she wished to speak to her daughter in private, was forced to request an appointment.

Melbourne could not have been more different from Sir John Conroy He never shouted; he sought the Queen’s company, encouraged her to talk, treasured her friendship, and was such a font of droll sayings and racy anecdotes that Victoria could hardly wait to commit them to her diary at the end of the evening. Melbourne slid effortlessly into the role of the doting father Victoria had never known. Within weeks of her accession, he was her dearest friend and indispensable companion as well as her chief adviser. King Leopold had fully expected to control his niece, both directly through his visits and letters, and indirectly by putting Baron Stockmar at the Queen’s side. Leopold and Stockmar were great political strategists, but they had failed to appreciate how much influence a handsome, sympathetic man of the world could have over an inexperienced young woman.