We That Are Left (59 page)

Authors: Clare Clark

âJubilee, of course, how clever you all are, my darlings. Well done, well done!'

The motley band of performers took a bow before wriggling through the audience to receive their kisses from their mother. Arthur pinched the lapels of his grimy gown between his thumbs and forefingers and grinned at Edward.

âAny wipers for me, my dear Dodger?' he asked.

Edward raised an eyebrow. âWhat a big nose you have, Grandmama.'

âPapier mâché. I fear the entire day nursery is now upholstered with the

Times

.'

âYou know, it's a great shame you don't go to more trouble with these things.'

Arthur laughed.

âThis was nothing. If Theo had had his way it would have been Buffalo Bill's Wild West. With real horses.'

Impatiently Kitty tugged on her father's sleeve.

âIs it our turn now, Papa?' she demanded.

âTomorrow, Kittycat,' Arthur said, lifting her into his arms. âPerhaps we might even persuade Mr Campbell Lowe to take a part.'

Edward shook his head.

âNot this time, I'm afraid. I have to be back in London by noon.'

âIsn't the House in recess?'

âI have meetings.'

âNo peace for the wicked, eh?'

âNot if I have anything to do with it.'

Behind them Theo and William had taken two of the sacks and were having a sack race between the piano and the window seat where Beatrice and Ursie quarrelled half-heartedly over a tangle-haired doll. A nursemaid came in and took Clovis for his bath. Charlotte kissed his toes as she handed him over, shaking her head at the black soles of his feet.

âHeavens,' she said. âDid your father rub you with coal?'

Clovis extended a starfish hand and she blew him a kiss. Then she reached over and touched Maribel's arm.

âWhere are you going?'

âTo my room. There's something I need to do.'

âIt can wait, surely? I've hardly seen you all day.'

Reluctantly Maribel settled back on the sofa.

âMust you go back tomorrow?' Charlotte asked. âI am not nearly done with you.'

âI must. Edward is to address some Fabian Society dinner tomorrow night and I have promised to go with him. It will be perfectly ghastly, of course.'

âI thought the Fabians were rather a spirited lot.'

âThey were once. Before they became Fabians and stopped reading novels and going to the theatre. Now they just wear solemn expressions and argue about strikes and slum clearances.'

âThe situation is so awful. I suppose at least they're doing something.'

âBut that's just it. They don't do. They talk and talk and talk while trying to exceed one another in glumness and the ugliness of their dresses. Oh, Charlotte, when did everyone get so political?'

âDearest, your husband is a Member of Parliament. They are supposed to be political.'

âIf it were only them I might be able to bear it. But it's all of London.'

âThen thank your lucky stars you are buried in the depths of the country where Socialism is yet to be invented. Forget the Fabians. Stay here and talk to me about poetry.'

It was a tempting offer. Though a great number of their friends were writers and artists and composers, nobody in London seemed to talk about poetry any more or painting or music. Instead promising playwrights and eminent poets exchanged grim stories of the sufferings of the match girls in Hackney and the coal miners in Yorkshire. Conversations, which had once drawn deeply upon intuition and imagination, had become lists of statistics: slum populations, mortality rates, hours of schooling, pence per hour or per gross. The Irish question, universal suffrage, free secular education, trade unions, prison reform, the minimum wage and the eight-hour working day. They lectured, protested, organised meetings, argued for revolution, and bemoaned the exasperating ignorance and passivity of the English working man.

Naturally Maribel did all of these things too. No one knew the arguments better than she did. She lectured and protested and organised and she tried to be glad, because the cause was just and good and it was what all their friends were doing. But for all that she couldn't help resenting it, just a little. There was no beauty in politics. It was all business.

âStay,' Charlotte coaxed. âThe Fabians will forgive you. One day. Or a week. I don't have to be back in London until next Monday.'

There was a loud shriek from the end of the room. Arthur was chasing the little ones with handfuls of straw that he threatened to stuff down their necks. Ursie, her crown askew, stood on a chair shouting encouragement while, by the fireplace, Edward tossed coins with George and Bertie, who called out their bets as the shillings spun in the air. In the corner behind the piano William and Theo held Matilda by her ankles and swung her backwards and forwards with such vigour that it seemed certain she would fly. The little girl screamed with delight.

Maribel smiled at Charlotte and shook her head.

âIf only I could,' she said.

Upstairs before dinner, while Edward played billiards with Arthur, Maribel took her writing case from the wardrobe and unlocked it. The envelope was thick, a rich creamy white, and slightly larger than was strictly conventional. The address was written in dark blue ink and placed, as it always had been, precisely in the centre of the envelope. The handwriting too was just the same, its letters slanted slightly to the right, the loops tucked neatly into themselves like hair ribbons.

She turned the envelope over, running her finger over its sealed edge.

Mrs Edward Campbell Lowe.

The last time they had seen one another, not one of those names had been hers. Very slowly she reached into the writing case, slid the silver letter opener from its leather pocket, and inserted it under the flap of the envelope. The paper sighed as she cut it. Inside was a single sheet of paper. Her fingers trembled as she drew it out.

My dear M

,I hope this letter finds you well

.

The letter was very short. Maribel read it through three times, holding the paper with the tips of her fingers as though she meant to tear it in two.

I shall be in London at the end of May and would be most grateful if you would consent to see me. I would not ask if it were not of the greatest importance. Naturally you may be assured of my utmost discretion. I shall write again when I know my arrangements.

Your affectionate mother

Maribel looked at the letter for a long time. Then, returning it to its envelope, she slid it once more beneath the unused envelopes in her writing case. On the mantelpiece the clock struck the hour. She should bathe or she would be late for dinner.

Instead she sat on the window seat, looking out over the garden. The rain had stopped at last and the evening light was as pale and new as the inside of a shell. Somewhere a pigeon cooed. She fumbled her cigarette case from her pocket and snapped it open. The symmetry of the white cylinders, the way in which they fitted precisely into the silver case, was soothing somehow, a refutation of human error. Maribel had her cigarettes rolled for her at Benson & Hedges in Old Bond Street and sent over in packages of one hundred. Mr Hedges boasted to his customers that his rollers were the most dextrous in London, that they could produce forty immaculate cigarettes in a single minute. Maribel had never been able to imagine that. Her fingers shook as she set a cigarette between her lips, struck a match. She smoked fiercely, her shoulders hunched, drawing the smoke into her skull. When the smouldering tobacco threatened her fingers she used the stub to light another.

She would have to tell Edward, of course. She could not meet her mother without telling Edward. And if she refused to meet her? She was not sure that she could make that decision without him either. She had told him a little of her family at the very beginning, of course, recounted foolish stories from her childhood as everyone did, but they were few and quickly forgotten. By that time the past was ancient history and dull history at that. It had nothing to do with her, with what she had become. She was a different person by then.

When other people enquired about her name or her family or remarked upon her unusual accent, she only shrugged and offered the briefest of explanations. Maria Isabel Constanza de la Flamandière was such a mouthful that she had always been known simply as Maribel. The only child of a French father and a Spanish mother, she had spent her girlhood in Chile where she had spoken both languages, French in conversation with her parents, a clumsy local version of her mother's tongue with the servants and shopkeepers. At the age of twelve she had been sent to live with her father's sister in Paris, where she attended a convent school which she disliked. In Paris she had met Edward. That was that, the extent of her history. Even the most persistent of questioners could not draw her further.

The story of her chance encounter with Edward was, by contrast, well known to everyone in their circle. One sunny May afternoon, aged only just eighteen, she had been walking in the Champs-Elysées when she was almost knocked off her feet by an unruly black horse. Its handsome rider had dismounted to beg her forgiveness and, in the sweet breathlessness of those first moments, their lives had been altered for ever. The daze of that Parisian afternoon had intensified into an impassioned courtship, conducted in secret, and then an elopement. Five weeks later in London she and Edward had been married.

They had honeymooned in Texas and in Mexico. Back in London with an eavesdropping servant to consider, they never talked of her family again. She had never confessed to Edward that, on their return from America, she had written a letter to her mother. She could think of no way to tell him, no explanation for her recklessness. At the time she had not concerned herself with reasons. When she had unpacked their boxes and discovered the notices of their wedding, cut from the London newspapers and sent to them by Edward's mother, she had folded them into a single sheet of writing paper on which she had scribbled a short note.

Mother

,Given the circumstances of our parting I thought you would be glad to know that, despite your steadfast belief that I would disgrace you, I am now married. We are currently resident at the above address in London, although we travel tomorrow to the family seat in Scotland. How provoking for you that you will not be able to boast about it. I would ask you not to reply to this letter but I should not wish you to worry unnecessarily.

M

She had posted the letter before she had had time to think better of it. That had been nearly ten years ago. Her mother had respected her wishes. She had not replied. Maribel had known that she would not. No doubt that was why she had risked writing in the first place, because there was no danger of the consequences. Her mother was a woman of irreproachable respectability whose abhorrence of scandal was as vital in her as blood. In ten years she had not written so much as a postcard.

And now, out of the blue, this. Her mother disliked travelling. She would not make the journey to London unless her business was urgent. As for her suggestion that they meet, it was frankly inexplicable. What was so important that it could not be said in a letter?

Visit

www.hmhco.com

or your favorite retailer to purchase the book in its entirety.

C

LARE

C

LARK

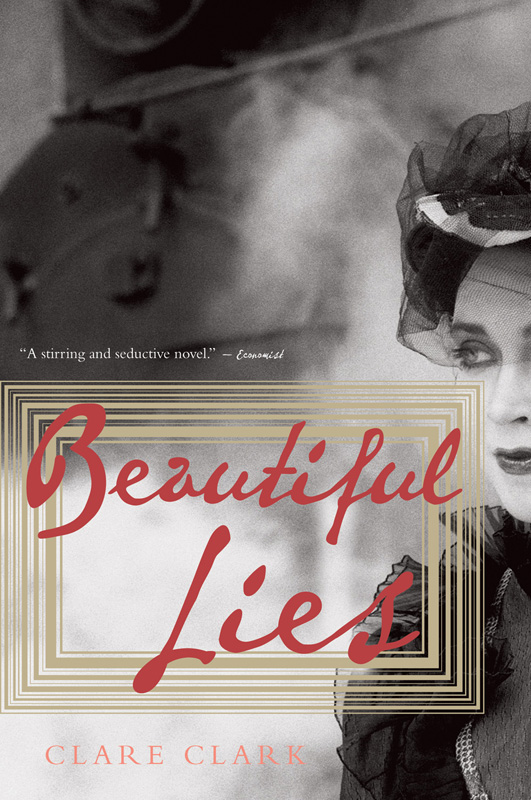

is the author of four novels, including

The Great Stink

, which was long-listed for the Orange Prize and named a

Washington Post

Best Book of the Year, and

Savage Lands

, also long-listed for the Orange Prize. Her work has been translated into six languages. She lives in London.