Washington Deceased

Read Washington Deceased Online

Authors: Michael Bowen

Â

Washington Deceased

A Washington D.C. Mystery

Michael Bowen

Poisoned Pen Press

Â

Â

Â

Copyright © 1990, 2013 by Michael Bowen

First E-book Edition 2013

ISBN: 9781615954506 ebook

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

The historical characters and events portrayed in this book are inventions of the author or used fictitiously.

Poisoned Pen Press

6962 E. First Ave., Ste. 103

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

Contents

To R. L. in Bethesda, with many thanks

“Washington is full of famous men and the women they married when they were young.”

âFanny Holmes

“â¦.tous les combats politiques sont douteux. Ce n'est jamais la lutte entre le bien et le mal, c'est le préférable contre le détestable.”

(“â¦.all political battle is dubious. It is never a struggle between good and evil, but between the preferable and the detestable.”)

âRaymond Aron,

Le Spectateur Engagé

,

pp. 289â90 (Julliard, Paris 1981)

Â

The human body isn't designed to survive collision with eight grams of lead moving twenty-five hundred feet per second, and Sweet Tony Martinelli's body didn't. His extinction had both positive and negative implications for former United States Senator Desmond Gardner. On the plus side, it perceptibly improved the immediate quality of Gardner's life. On the other hand, Gardner thought it might interfere with his parole application.

Gardner had already gotten Richard Michaelson involved by the time Sweet Tony bought it, so the story has to start at a time when he was still alive.

***

About ten minutes before noon on the last full day of Martinelli's life, Wendy Gardner hurried down Connecticut toward Massachusetts Avenue where she would turn left and, she hoped, quickly find the Brookings Institution. Two or three undisciplined clusters of blond hair strayed over her forehead.

In her left arm she cradled a sack holding a thin, hardcover book she had just bought. Its title was

Bright Lines and Slippery Slopes: Nine Fallacies in Current Foreign Policy Discourse

. Richard Michaelson had written it. A true child of Washington, Wendy had stopped to buy the improbably named volume, even though she was running late and didn't have the slightest intention of ever reading it. She thought that she might ingratiate herself with Michaelson by having a copy of it with her when she met him.

Wendy Gardner was at this time a sophomore at the principal public university of the midwestern state that her father had served for eleven years in the United States Senate. She was five-and-a-half feet tall and would just have nudged into the featherweight class had she boxedâan activity for which she had the disposition but not the aptitude.

She had the virtues of her deficiencies. She was tolerant and open-minded, to the point of regarding “everything's relative” as a dogmatic, all-purpose moral judgment. Viewing recreational sex as immature and promiscuity as irresponsible, she thought that sexual intimacy should be confined to relationships involving love and commitment. She had been in love five times. Liberated from the stranglehold of juvenile idealism, she saw herself as an unflinching, hard-bitten realist, gazing cold-eyed and without comfort of illusion on the world as it was.

This was like viewing Sylvester Stallone as a commando: It was possible only until she met the real thing.

Which she was about to do.

Arriving too late to be introduced to Michaelson before the start of the Brookings colloquy where she was supposed to meet him, Wendy found herself sitting against the wall of a windowless conference room in a standard-issue Washington office suite, watching the confabulation itself proceed. Michaelson sat at the head of a long, blunted-oval table that dominated the room. He had snow-white hair and tight, chiseled features, as if in his long association with Washington his face had come to resemble the city's less derivative statuary. His fair skin, untanned and unburned, set off eyes so dark brown they seemed to Wendy to be black. Except for the pinkie on his left hand, half of which was missing, his fingers were long and elegant. Wendy correctly surmised from the fingers that Michaelson was tallâabout six-two, in factâand that when he stood his rather spare frame would make him seem even taller.

Fooled by the hair, Wendy guessed that Michaelson was near sixty-five. He had actually just turned fifty-seven. Had she seen him on the street, in his brown-tone tweed suit, white shirt and brown-and-mustard bow tie, she would have guessed that he was a professor at George Washington University or a lobbyist for the American Association of Retired Persons.

Around the rest of the table sat six men and three women. They seemed to Wendy incredibly youngâearly to middle twenties, all of themâand Wendy thought that they looked like wonks. When Michaelson spoke they took notes with the kind of bizarre intensity that Wendy associated with the tools in Survey of English Literature who really cared about whether John Donne was a better poet than Richard Lovelace.

She wouldn't have guessed that these people were all on campaign staffs. And she would never have imagined that, within thirty months or so, one or more of them would probably be helping a President elect of the United States pick a covey of senior advisors.

As she got settled, one of the wonks was finishing a question.

“âand so do you feel you have exposed the moral bankruptcy of the policy of constructive engagement toward South Africa?”

“No. What I have tried to expose is the logical incoherence of the stated rationale for that policy,” Michaelson said. His voice was low and resonant, his cadence unhurried, his tone dry and detached.

“The premise of your argument being, however, that the continued existence of apartheid is unacceptable.”

“The premise of my argument is that the continued existence of apartheid is unlikely. âUnacceptable' is a term that I wouldn't use in that context.”

“Why not?”

“Because when you are doing foreign policy I don't think that you should say something is unacceptable unless you mean it.”

“In the case of South Africa, some of us do mean it.”

“I doubt that very much.”

“Believe it,” the wonk persisted. “Some of us are prepared to recommend complete diplomatic isolation and full-scale trade sanctions.”

“Fair enough,” Michaelson nodded. “But if you take those steps and they don't put an end to apartheid and white minority rule in South Africa, what do you do then?”

“You've done all you can do.”

“I think not,” Michaelson replied. “There are certainly other things you

could

do: military aid to insurgents; U.S. air and naval blockade; invasion of South Africa by U.S. military forces; and so forth. The question is, are you really willing to do them?”

“Not all of them, certainly.”

“Nor am I. I take it then we can agree that apartheid and white minority rule are lamentable and reprehensible but not unacceptable since, under certain circumstances, you would accept them.”

“But in that sense there's nothing that's unacceptable, is there?” someone else asked.

“Nothing except impairment of the sovereignty, political independence or territorial integrity of the United States. But that's a rather critical exception, isn't it?”

It seemed to Wendy that Michaelson was being rather rude to his young interlocutors. She wondered why they all seemed not just respectful but actually rather taken with him. What Wendy saw as rudeness, however, was Michaelson's refusal to condescend to the people he was talking to. He knew exactly what they wanted to hear and he understood perfectly well how to say it and make it ring with conviction. Instead of doing that, he was telling them what he really thought.

Vaguely uncomfortable with what she was hearing, Wendy stopped paying attention to the conversation and sought distraction in Michaelson's book.

She turned first to the back flap of the dust jacket, where she saw a flattering halftone of Michaelson and a one-paragraph biography that emphasized the positions he had held before retiring after thirty-five years in the Foreign Service: consul, desk officer, commercial attaché, political counsellor, desk officer again but this time for a country she had heard of, deputy chief of mission and area director. None of them sounded like very exciting jobs. She didn't notice that there weren't quite enough of them to add up to thirty-five years of active duty in the Foreign Service.

She shrugged and opened at random to the text. “The oft-heard prescription that, âThe United States should prefer negotiation to military force,' ” she read, “exemplifies the fallacy of the false alternative. The use of force isn't an alternative to negotiation; it is a form of negotiation.”

Wendy blinked and shook her head. She closed the book and decided to pay more attention to the discussion.

“You described the premise of your position as being that the continued existence of apartheid is unlikely,” a wonk not heard from up to now was saying. “I take it then you believe that, eventually, majority rule in South Africa is inevitable.”

“If by majority rule you mean rule by a minority that is the same color as the majority of people in the country, then I think it is quite likely indeed.”

“In other words, since blacks are going to be running things in South Africa in the foreseeable future, the time to get on the winning side is now.”

“Yes. As Damon Runyon put it, the race may not be always to the swift, nor the battle to the strongâbut that's the way to bet.”

“Would you allow any role to

moral

value judgments in making foreign policy?”

“To one, at least.”

“Namely?”

“That in the struggle between freedom and tyranny, freedom should win.”

“That is, freedom should win globallyâeven at the cost of important values in particular places.”

“That is correct.”

“So that national interest excuses a multitude of sins.”

“Yes. But one sin national interest never excuses is believing your own propaganda.”

“That's really what you're saying is wrong with constructive engagement, isn't it?” Wonk 1 asked. “That it's based on believing our own propaganda.”

“Exactly,” Michaelson said, his voice suddenly quieter. “The present policy is sentimental, based on the fond but groundless hope that a choice implicating the knowing acceptance of evil will never have to be made. That isn't the way the world is. At the level of superpower rivalry, foreign policy is carried out in a pure, Hobbesian state of nature: a pitiless struggle of all against all, conducted without law, without faith, and without joy.”

Wendy Gardner sat unnoticed in an eerie stillness as the colloquy continued. She had walked into the room thinking that Richard Michaelson was probably a pedantic, curmudgeonly old fart. She no longer thought that. She now thought he was a cold, Machiavellian monster. Her gut churned at the thought of asking him for anything.

Notwithstanding which, as the conference wound down, she braced herself to do exactly that.

***

“Senator Gardner's daughter?” Michaelson asked a bit later when she had finally been able to make her way to him.

“Yes.”

“This is a delightful surprise, Ms. Gardner. I've known Desmond Gardner for many years. There are a couple of stories about us that I hear are still being told in the diplomatic and political worlds.”

Wendy's spirits sank a bit. Outside his state, where his name still held some magic, people had tended since Gardner's conviction and imprisonment to downplay or altogether forget their past associations with him. She concluded that Michaelson must have forgotten that her father was a convicted felon, and that any inclination Michaelson had to help would cool as soon as she brought that complicating detail up.

“Good,” Wendy said, forging ahead. “You seeâ”

“He's at Fritchieburg now, isn't he?”

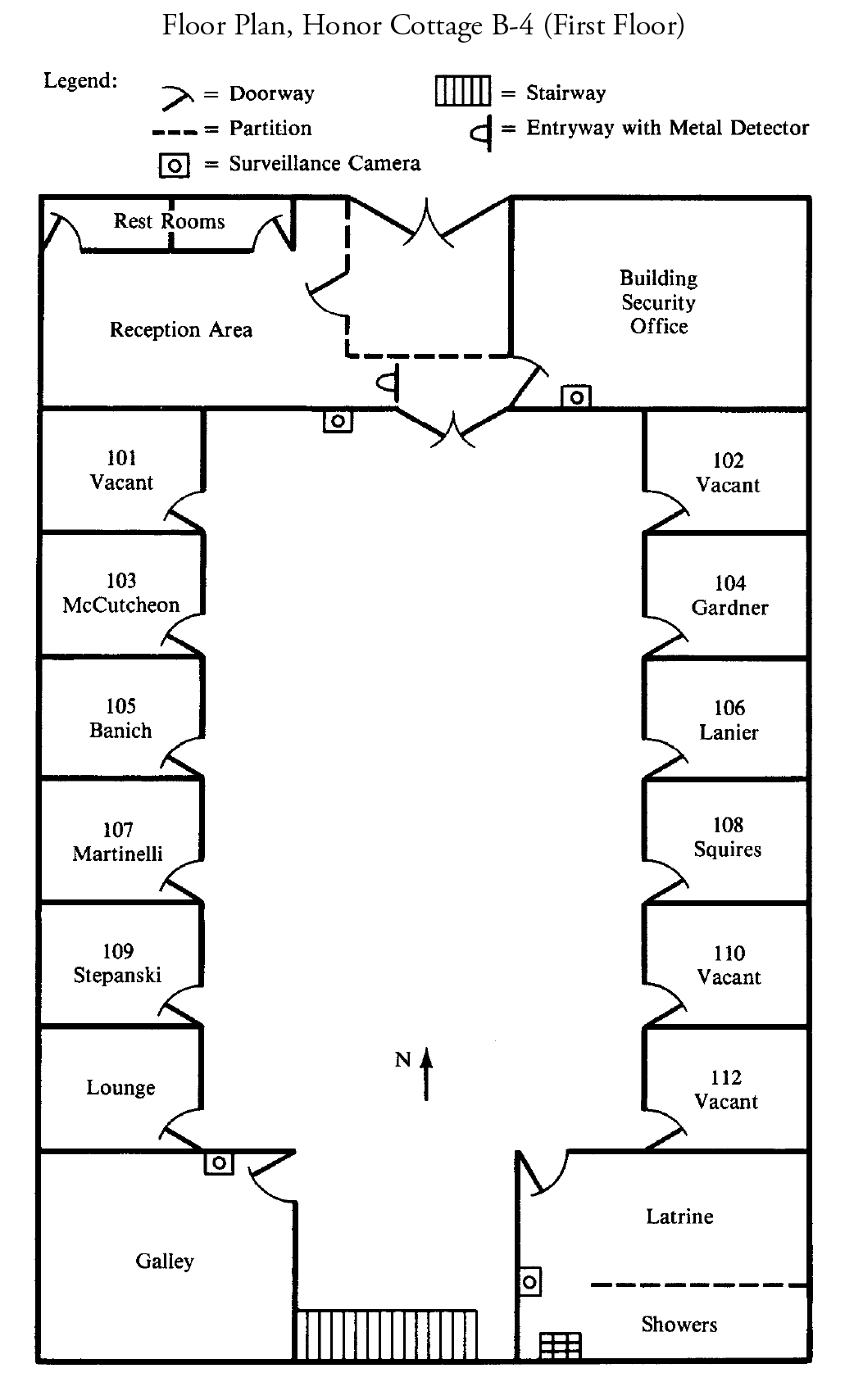

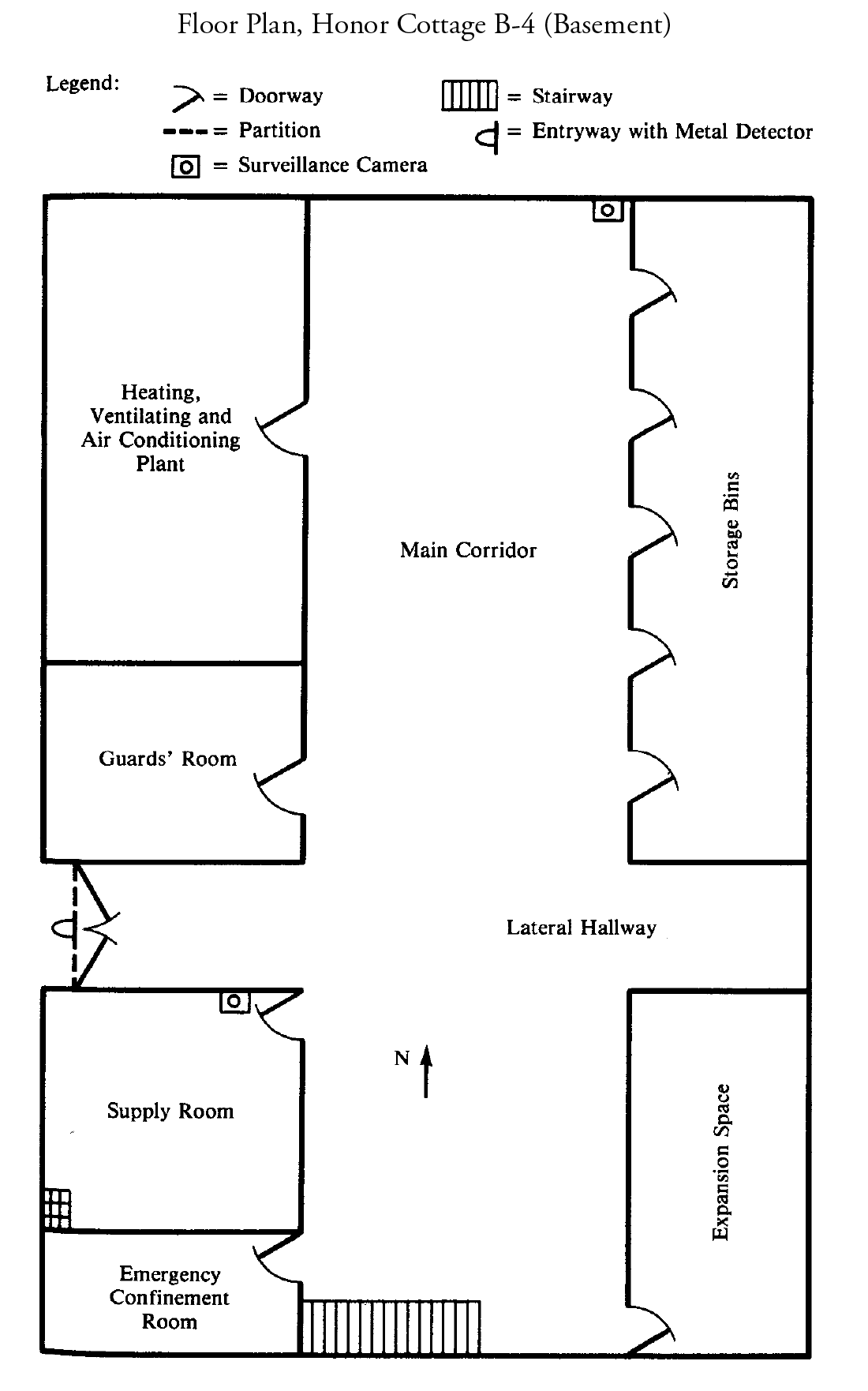

“Yes,” Wendy stammered, surprised at this colloquial reference to the Federal Minimum Security Correctional Facility outside Fritchieburg, Maryland, where her father was an inmate.

“Excuse me for interrupting. You were about to say something.”

Wendy took a deep breath and prepared to launch into the rapid but detailed explanation of her father's plight that she had gotten ready to try to keep Michaelson from telling her no before she could get the salient facts out.

“He sent me to ask for your help, so I'm cutting the last week of classes before spring break to come out here. You see, he's afraid that he's getting squeezed for some information that he doesn't have and that his parole could be jeopardized by something that's going on that he doesn't understand.”

“I'll be glad toâ”

“He's even afraid that he may be in physical danger,” Wendy continued. “I could tell over the phone that he was upset, and there seem to be a lot of people in Washington who can't remember who he was anymore. He told me to come to you and see, ahâ”

“I said yes,” Michaelson interjected gently as Wendy groped for her next word.

She managed to choke off the flow of sounds and look up. “Excuse me?”

“The answer is yes. I'll help Senator Gardner in any way that I can. As I said, he and I go back a long way.” Michaelson glanced at his watch. “Let's find a sandwich and talk this over in the sunshine.”