War: What is it good for? (44 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

But when the League of Nations took shape in 1919, it looked nothing like this. It had no coercive powers. Its achievements in bringing refugees home, stabilizing currencies, and gathering statistics were extraordinary, but it could not fill the vacuum left by the British globocop. Many critics suspected that not competing with Britain was in fact the whole point of the exercise; after all, they observed, when Lloyd George declared, “I am for a league of nations,” he had added, “In fact ⦠the British Empire

is

a league of nations.” The league's constitution was based largely on British proposals, and one of its first acts was to approve British and French “mandates”âin effect, coloniesâin much of the Arab world.

The U.S. Congress wanted nothing to do with it, seeing it as just one more entangling alliance; Jawaharlal Nehru, India's future prime minister, wrote from a British jail that “the League of Nations ⦠looks forward to a permanent dominance by these Powers over their empires”; and Lenin denounced it as a “stinking corpse” and “an alliance of world bandits.” The only real alternative to a globocop, the Soviets announced in 1919, was communism itself, which would “destroy the rule of capital, make war impossible, abolish state frontiers, [and] change the entire world into one cooperative community.”

The problem with the communist solution, however, was that the Bolsheviks had been killing from the moment they seized power, and seemed to relish it. “Comrade!” Lenin wrote to one commissar in August 1918. “Hang (and I mean hang so that the

people can see) not less than 100

known kulaks [prosperous peasants], rich men, bloodsuckers ⦠Do this so that for hundreds of miles around the people can see, tremble, know and cry: they are killing and will go on killing the bloodsucking kulaks â¦

“Yours, Lenin.

“P.S. Find tougher people.”

In March 1919, when Lenin called the League of Nations a stinking corpse, more than five million men were fighting a particularly horrible civil war in the new Soviet Union. This ultimately killed even more Russians (perhaps eight million, counting deaths from famine and disease) than the Germans had done. Britain and France had decided as early as May 1918 that they had to intervene, and serious fighting began on November 11, the very day that quiet fell on the Western Front. In 1919 a quarter of a million foreign troops (mostly British, Czech, Japanese, French, and American, but including Polish, Indian, Australian, Canadian, Estonian, Romanian, Serbian, Italian, Greek, and even Chinese contingents) served on Russian soil.

If the league really had been a capitalist conspiracy, Lenin and his henchmen would not have lasted long enough to condemn it. But as it was, with no globocop overseeing operations, the interventions in the Russian Civil War broke down in disorder. By mid-1920, all forces but the Japanese had withdrawn, and Soviet armies were bearing down on Warsaw. After gobbling up Poland, the Soviets planned to carry communism to Germany, which had just finished putting down its own Bolshevik revolution. For a few weeks in the summer of 1920 it looked as if Lenin's boast that the red flag would sweep away state frontiers might actually come true, but as the Red Army outran its supplies, the Poles rallied and hurled it back. At the

end of August, Polish horsemen even won Europe's last big cavalry battle, at Komarów. Twenty-five thousand men charged and countercharged, sabers drawn, much as mounted warriors had been doing for the previous two thousand years, but this time they did it with machine guns clattering and high explosive shells bursting all around them.

Over the next few years, the Soviets quietly dropped their talk of world revolution. Sporadic fighting continued over the carcasses of the empires cast down by World War I, but for a while at least, the world seemed to be getting along just fine without a globocop. International trade recovered, and by 1924 incomes in most places were back where they had been in 1914. The world was finally putting the horrors of the war behind it. Between 1921 and 1927, the Dow Jones index of American stocks quadrupled; between 1927 and 1929 it almost doubled again, peaking at 381.17 points on September 3, 1929.

Ten years later to the day, Britain and France once again declared war on Germany.

Death of a Globocop

The nineteenth-century world-system finally died over the last weekend of October 1929.

Despite eighty-five years of arguments, we still don't know exactly how it started. “The 1929 crisis is a substantial curiosity,” says the financial historian Harold James, “in that it was a major event, with truly world-historical consequences (the Great Depression, even perhaps the Second World War), but no obvious causes.” For whatever reason, Wall Street traders lost their heads on Wednesday, October 23. Four billion dollars of wealth (the equivalent of $53 billion today) evaporated. By Thursday lunchtime, another $9 billion of American riches had evaporated. Then the markets rallied, buoyed by an alliance of bankers buying up the shares no one wanted, but on Monday the roof really fell in. By Tuesday afternoon the Dow had lost almost a quarter of its value, and by the summer of 1932 a dollar of stock bought at the market's peak on September 3, 1929, was worth just eleven cents.

The decade between September 3, 1929, and September 3, 1939, saw global finance melt down, sweeping away what was left of the integration that had made the nineteenth-century world-system work. Into the 1870s and even beyond, Britain had regularly acted as the lender of last resort, accepting that being a globo-credit union was part of the globocop's job.

But now there was no globocop; it was every government for itself. One after another, they walled off their economies, raising barriers against competition and financial contagion. The United States alone introduced twenty-one thousand tariffs to keep out imports, and by the end of 1932 international trade had shrunk to one-third of what it had been in 1929.

It was this that killed Britain's last pretensions to playing globocop. Like everyone else, governments in London retreated behind tariffs. Defense spending fell even further, and in 1932 the chiefs of staff admitted that the navy could no longer defend the empire east of Suez. War, they conceded, would “expose to depredation, for an inestimable period, British possessions and dependencies, including those of India, Australia and New Zealand.”

Not surprisingly, the possessions and dependencies being so exposed reacted badly. The white settler dominions made it clear that London should not take their support for granted if another war came, and India, for so long a central pillar in the world-system, began going its own way. Britain opened negotiations with Gandhi's noncooperation movement in 1930, and in 1935 it made major concessions to Indian political parties.

The 1930s collapse shook the British ruling class to its core. “It is the virtue of the Englishman,” a Cambridge don had written in 1913, “that he never doubts,” but over the next twenty years this certainty faded fast. Even to its rulers, the whole globocop exercise was starting to seem just a little bit pointless. The most eloquent doubter was surely George Orwell, an Old Etonian whose five-year stint in the empire's police force in Burma turned him into one of Britannia's fiercest critics. However, he was hardly alone. “All over India,” he observed, “there are Englishmen who secretly loathe the system of which they are a part.” Once, he wrote, he had shared a compartment on an overnight train ride with an (English) officer of the Indian Education Service. “It was too hot to sleep,” he said, “and we spent the night in talking.”

Half an hour's cautious questioning decided each of us that the other was “safe”; and then for hours, while the train jolted slowly through the pitch-black night, sitting up in our bunks with bottles of beer handy, we damned the British Empireâdamned it from the inside, intelligently and intimately. It did us both good. But ⦠when the train crawled into Mandalay, we parted as guiltily as any adulterous couple.

The empire still had its boosters, of course. “There are Englishmen who reproach themselves with having governed [India] badly,” one of these

admirers wrote. “Why? Because the Indians show no enthusiasm for their rule. I claim that the English have governed India very well, but their error is to expect enthusiasm from the people they administer.”

This fan was Adolf Hitler. The solution to the world's uncertainties, he insisted, was force, not self-doubt, and as the democracies of the 1930s struggled with sluggish growth, faction-ridden ruling coalitions, unemployment, and social unrest, it began to look as if he might be right. Violent strongmen (some on the left, but most on the right) seized power in Europe, East Asia, and Latin America. All made the same bet: that without a globocop, force was the solution to their problems.

In many ways, the Soviet Union was the model for them all. Its leaders seemed to have discovered the secret of success in the uncertain postwar world: that more violence worked better than less violence. Stalin shot tens of thousands of his subjects, locked a million in gulags, shipped millions more around his empire, and confiscated so much grain that ten million starved, and as he did so, the closed, inward-turned, centrally planned Soviet economy grew by 80 percent between 1929 and 1939. This dwarfed the performance of the open-access, globally linked, capitalist economies. Britain expanded by a respectable 20 percent across the same decade, but France managed only 3 percent, and the United States just 2 percent.

Cheered by the success of internally directed violence, and undeterred by the fact that he had just had all the best officers in the Red Army shot, Stalin turned violence outward in 1939. He sent troops into Finland, the Baltic States, Poland, and Manchuria, and on the last of these fronts the Soviets clashed with an equally aggressive Japan, which, after prospering as a commercial power since the 1870s, had been hard-hit by the new barriers to trade in the 1930s. “Our nation seems to be at a dead-lock,” Lieutenant Colonel Ishiwara Kanji observed, “and there appears to be no solution for the important problems of population and food”âunless, that is, Japan adopted Ishiwara's solution: “the development of Manchuria and Mongolia [whose] natural resources will be sufficient to save [Japan] from the imminent crisis” (

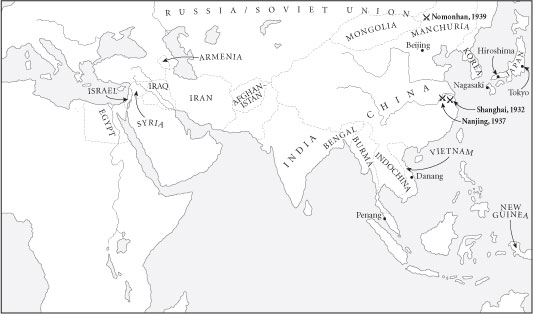

Figure 5.9

).

Figure 5.9. End of empire: the wars for Asia, 1931â83

Ishiwara and a gaggle of junior officers went rogue, invading Manchuria (then part of China) in 1931 without any orders to do so. Ishiwara half expected to be court-martialed, but when it became clear that the invasion was going well and that there was no invisible fist to punish them, politicians in Tokyoâthemselves drowning in unknown unknownsâalso embraced force. When the League of Nations insisted that they withdraw, they instead withdrew from the league.

British and American politicians fulminated but did nothing. A Japanese attack on Shanghai in 1932 did shock Britain into dropping the budgeting assumption (in place since 1919) that it would not have to fight a major war within the next decade, but still Britain hesitated to rearm, largely out of fear of stoking inflation.

Five years later, Japan struck again, overrunning northern China. Once more, violence paid. With newly conquered markets to sell in and burgeoning armies to provision, Japan saw its GDP grow more than 70 percent in the 1930s. “We really got busy,” one munitions worker remembered. “By the end of 1937, everybody in the country was working. For the first time, I was able to take care of my father. War's not bad at all, I thought” (

Figure 5.10

).

Figure 5.10. “War's not bad at all”: burned children in Shanghai's bombed-out railway station, 1937

Japan outdid the Soviets at externally directed violence. After storming Nanjing in southern China in December 1937, Japanese soldiers raped and murdered perhaps a quarter of a million people. “We took turns raping them,” one soldier confessed. “It would be all right if we only raped them. I shouldn't say all right. But we always stabbed and killed them.” When a Tokyo journalist recoiled at seeing men hanging by their tongues from hooks, an officer explained things to him. “You and I have diametrically different views of the Chinese. You may be dealing with them as human beings, but I regard them as swine. We can do anything to such creatures.”