War: What is it good for? (37 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Steam power smashed the last barriers to European commerce. For centuries, the vast distances separating Europe from East Asia had kept Western trade to a mere trickle, while the interiors of Africa and Asia had been

beyond the merchants' reach altogether. Steam changed that. Engineers immediately saw that steam engines could be mounted on wheels and that these wheels could paddle ships across oceans and carry trains down tracks. Steam could do the work of the winds and waves in transport, much as it was doing the work of muscles in manufacturing. Steam could swallow space.

The British led the way. “The earth was made for Dombey and Son to trade in,” announced Charles Dickens in his great novelâ

Dombey and Sonâof

pride, prejudice, and global commerce. “The sun and moon were made to give them light. Rivers and seas were formed to float their ships; rainbows gave them promise of fair weather; winds blew for or against their enterprises; stars and planets circled in their orbits, to preserve inviolate a system of which they were the centre â¦

A.D.

had no concern with anno Domini, but stood for anno Dombeiâand Son.”

Dickens wrote these words in 1846 (anno Domini, that is). In 1838 a British steamship had crossed the Atlantic in fifteen days, ignoring headwinds and currents to average an unheard-of ten miles per hour. The next year, an even more extraordinary ship sailed from England for China: the

Nemesis,

an all-iron steamship, armed with cannons and rockets. So odd did this boat seem that even its captain conceded that just “as the

floating

property of wood ⦠rendered it the most natural material for the construction of ships, so did the

sinking

property of iron make it appear, at first sight, very ill adapted for a similar purpose.”

The

Nemesis

was on its way to East Asia because of an extraordinarily sordid quarrel. Chinese governments, deeply suspicious of Western traders, had for generations penned them into tiny enclaves in Macao and Guangzhou and limited what they could buy and sell. The merchants, however, found that whatever the Chinese government might say, Chinese customers were eager for their goods, especially opium. Since the world's best opium grew in British-controlled India, business was goodâuntil, in 1839, Beijing declared a war on drugs.

Chinese officials confiscated a fortune in opium from British drug dealers. After some dubious lobbying, the dealers persuaded the government in London to demand compensation, plus a base at Hong Kong, and the right for traders and merchants (including drug dealers) to enter other ports. The Chineseâunderstandablyârefused, confident that distance would protect them, but the

Nemesis

and a small British fleet quickly showed that this assumption no longer held.

The technological gap between the two sides in this Opium War was

just astonishing. Chinese junks, one British officer observed, looked “exactly as if the subjects of [medieval] prints had assumed life and substance and colour, and were moving and acting before me unconscious of the march of the world through centuries, and of all modern usage, invention, or improvement.” Chinese forts crumbled under the intruders' guns, and in 1842 Beijing gave Britain what it demanded.

Steamships now flooded China's coastal cities with Western goods, and in 1853 an American flotilla, looking for coaling stations, steamed boldly into Tokyo Bay. It cowed the Japanese government without even firing a shot. Back in Washington, the president ignored his commodore's suggestion that he now annex Taiwan, but the lesson was clear: no country with a coastline was now safe from the West.

Nor, for that matter, were countries without coastlines. What steamships did at sea and up rivers, railroads did in the interior. Here, though, aggression was spearheaded less by Europeans than by their settlers overseas. Europe's governments had discovered early on that colonists separated from home by thousands of miles felt little need to follow orders. Since the sixteenth century, Lisbon, Madrid, London, and Paris had issued rafts of regulations on trade, tea, slaves, and stamps, but Brazil, Mexico, Massachusetts, and Quebec had ignored them. Even when kings' demands were quite mildâthat colonists pay for their own defense, for instanceâwhite settlers regularly refused and fought back against efforts to coerce them. After Britain lost the United States, it only held on to Canada, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand by giving them most of what the American rebels had demanded. France sold off its last North American holdings in 1803; by 1825, Spain had lost all its American holdings except Cuba and Puerto Rico, and at that point Portugal's stake had been wiped out altogether.

European governments had hesitated to push inland, worrying about the costs of conquest, and sometimes even about the rights of local people. The white settlers, however, had fewer qualms. Americans were streaming across the Appalachians even before the ink was dry on the Declaration of Independence, and the Chickamauga Wars (1776â94) began a century of attacks on natives. In the 1820s white Australians followed the same path, conquering Tasmania and breaking into their continent's interior. In the 1830s, South African Boers struck out on their own to escape British regulation and at the Battle of Blood River shot dead three thousand Zulus for a loss of just three wounded Afrikaners. In the 1840s New Zealanders went to war with the Maori and the United States reached the Pacific, finally stretching from sea to shining sea.

A great native retreat was under way, but what turned it into a rout was the railroad. In the 1830s Americans laid down twice as much track as the whole of Europe combined, then doubled this in the 1840s and tripled it again in the 1850s. The iron horse moved millions of migrants westward and carried the supplies the army needed as it herded Native Americans into ever-more-remote reservations. By the 1880s, railroads were also bringing miners from Cape Town to dig up gold and diamonds in Transvaal and taking Russian settlers and soldiers to Samarkand. In 1896 a British army striking into Sudan to crush an Islamist uprising even built a railway as it went.

The last barrier to Western expansionâdiseaseâcollapsed between 1880 and 1920. In the space of a single lifetime, doctors isolated and conquered cholera, typhoid, malaria, sleeping sickness, and the Black Death. Only yellow fever (responsible for thirteen out of every fourteen deaths in the Spanish-American War of 1898) held out until the 1930s.

The consequences were felt all over the tropics, but most powerfully in Africa. As late as 1870, hardly any Europeans had gone more than a day or two's walk from the coast, but by 1890 steamships and railroads were moving thousands of them inland, and medicine was keeping them alive when they got there. For centuries, the only way to get ivory, gold, slaves, and anything else Europeans wanted had been by cutting deals with long chains of African chiefs, each of them taking a slice of the profits, but now the Europeans could take charge themselves.

As often happens, solving one problem just created another. Quinine and vaccines worked just as well on French and Belgians as on English and Americans, with the result that traders who braved deserts, jungles, and hostile natives kept finding that other Europeans had got there ahead of them. In a rerun of what had happened in America and India centuries earlier, the men on the ground lobbied their governments to take over great slices of Africa and keep other westerners out.

Annexation often needed only a few hundred Western soldiers. Africans and Asians had worked hard at catching up with European firepower since the 1750s (after a particularly hard-fought battle in India in 1803, the British commander confessed, “I never was in so severe a business in my life or anything like it, and pray to God, I never may be in such a situation again”), but Western firepower just kept getting better. In the 1850s, proper riflesâthat is, guns with grooves inside the barrel to make bullets spin, increasing their range and accuracyâcame into general use, with devastating results.

Steam-powered factories churned out rifles by the ten thousands, each one perfectly machined and far less likely to misfire than preindustrial muskets. Americans particularly shone at this mass production; British observers were astonished in 1854 when a workman at the Springfield Armory in Massachusetts randomly chose ten muskets made at the factory across the previous decade, disassembled them, threw the parts into a box, and reassembled them into ten perfectly working guns. The British immediately bought American machinery and founded the Enfield Armoury. “There is nothing that cannot be produced by machines,” Samuel Colt told them.

When both sides had rifles and knew how to use them, as in the American Civil War, thousands of men could be mowed down in minutes. September 17, 1862, remains the single bloodiest day in the history of American armies, with nearly twenty-three thousand men killed or wounded at the Battle of Antietam (usually called Sharpsburg in the South). In Africa and Asia, though, Europeans rarely faced much return fire from rifles. General Henry Havelock's comment in 1857 after annihilating a huge Indian army that ambushed his tiny British columnâ“In ten minutes the affair was decided”âcould be applied to dozens of mid-century slaughters, from Senegal to Siam. The Gatling gun (patented 1861), Carnehan and Dravot's beloved Martini-Henry rifle (introduced 1871), and the fully automatic Maxim gun (patented 1884) made the firepower gap between the West and the rest so wide (

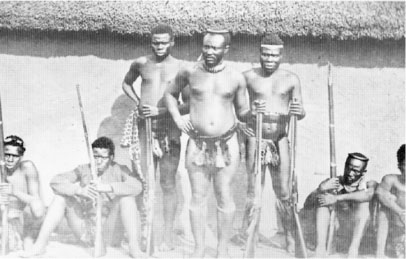

Figure 4.12

) that only rank incompetence, of the kind British officers exhibited against the Zulus at Isandlwana in 1879 and Italians against Ethiopians at Adwa in 1896, could close it.

Figure 4.12. Mind the gap: by 1879, when this photograph was taken, the firepower gap between Western and non-Western armies was enormous. Here, the Zulu prince Dabulamanzi kaMpande (center) and his men display their motley collection of shotguns, hunting rifles, and antique muskets. Dabulamanzi would soon be repulsed from Rorke's Drift, despite outnumbering the defenders ten to one. Only when Western officers were extremely incompetent could non-Western armies win.

By the nineteenth century's end, Western armies went more or less wherever they wanted, and Western navies had even more freedom. European ships had had no serious rivals since the seventeenth century, but the nineteenth-century introduction of steel-plated steamships and explosive shells made resistance futile. The first clash of ironclads, the point-blank shoot-out between the

Monitor

and the

Merrimack

3

during the American Civil War, had amazed onlookers, but by the 1890s battleships were displacing fifteen thousand to seventeen thousand tons, steaming at sixteen knots, carrying four twelve-inch guns, and fighting duels at five miles' range. European governments spent fortunes on these ships, only for them to become

instantly obsolete in 1906, when Britain launched HMS

Dreadnought,

complete with turbine engines, eleven-inch armor, and ten twelve-inch guns. Five years later British battleships switched from coal to oil, and by then, with a single exception that I will return to in

Chapter 5

, the maritime gap between the West and the rest was absolutely unbridgeable.

When I was a little boy, my grandmother had a battered globe that must have been made right around this time. Its paper surface was bubbled and peeling, but it fascinated me. British newspapers in the 1960s were full of stories of national humiliation and the retreat from empire, but here, in this little time capsule, everything was different. Two-fifths of the planet was colored pink, for the British Empire. “On her dominions the sun never sets,” Scotland's oldest newspaper had rejoiced as early as 1821. “While sinking from the waters of Lake Superior, his eye opens upon the Mouth of the Ganges” (

Figure 4.13

).

Figure 4.13. The scale of victory: by 1900, Europeans had conquered 84 percent of the earth's surface (shown in light gray; British Empire shown in dark gray).

Altogether, Europeans or their former colonists ruled five-sixths of the world, but not even Granny's globe captured the full magnitude of Europe's victory in the Five Hundred Years' War. Western dominion was so profound that historians regularly suggest that the word “empire” does not

really do it justice. Rather, they propose, we should think of a nineteenth-century “world-system,” in which formal empires ruled from European capitals were just oneâand not necessarily the most importantâpart of a wider web of connections binding the entire earth.