War: What is it good for? (15 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

The consequence of the brutality, though, was that fewer cities came to rule over more people, and by 3100

B.C.

, when it built its six-mile wall, Uruk seems to have exercised some kind of control over much of Sumer. As far north as what is now Syria, some sitesâespecially Tell Brak, the scene of heavy fighting around 3800

B.C.

, and Habuba Kabiraâlook as if they were conquered or colonized from Uruk.

This larger Uruk society was developing more complex internal structures. It had genuine cities, with populations running into the tens of thousands, and kings who claimed descent from gods. Eventually, stationary bandits drew up law codes, commanded bureaucracies that kept written records, extracted taxes, and, they liked to say, acted as shepherds to their people.

The first Leviathans oversaw societies that were less equal than those of earlier times but richer and probably safer. In the absence of statistics, we are of course largely guessing about this, but in the highly caged Nile Valley, where deserts trapped farmers into a narrow strip of land, it seems undeniable. After several centuries of fighting, three small states emerged in the upper Nile Valley by 3300

B.C.

By 3100 only one still stood, and its king, Narmer, became the first pharaoh to rule the whole of Egypt. He and his successors stamped out war in their five-hundred-mile-long kingdom and took stationary banditry to a whole new level. Where other kings of the third millennium

B.C.

claimed to be like gods, the pharaohs claimed to

be

gods, and where other kings built ziggurats, pharaohs built pyramids (the Great Pyramid at Giza, weighing in at a million tons, is still the heaviest building on earth).

Megalomaniacal as it now seems, divine kingship worked well to centralize power. So far as we can tell, Egypt's aristocrats began concentrating so hard on competing for royal favor that they largely gave up violent competition with one another, in more or less the same pattern that Elias saw happening in Europe forty-five centuries later. The art and literature that survive from the third millennium

B.C.

only allow us to form very general impressions, but the overwhelming implication is that Old Kingdom Egypt was, by ancient standards, a very peaceful place. Leviathan was outrunning the Red Queen.

Stand Your Ground

Southwest Asia and Egypt (which archaeologists usually lump together as the Fertile Crescent) led the way in bringing forth Leviathans, but over the centuries that followed, other farming societies around the lucky latitudes moved along much the same path. As we might expect, there is generally a good fit between the date when farming began and the date when cities, Leviathans, and fortifications began. The denser the availability of domesticable plants and animals at the end of the Ice Age, the sooner people took up farming, and the sooner they took up farming, the sooner caging turned their wars productive.

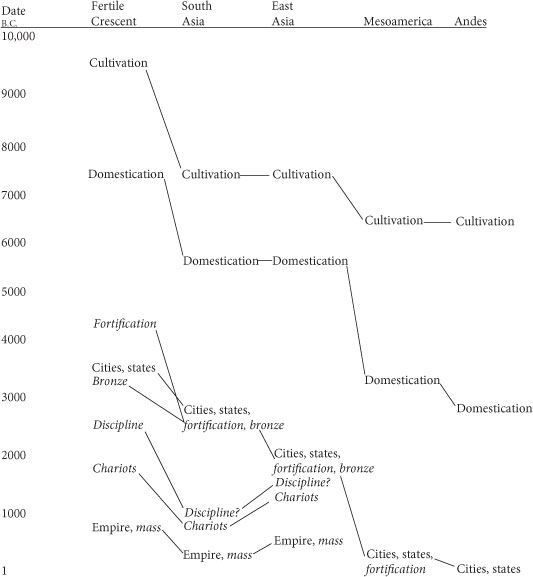

I find that nothing brings out patterns quite like a good chart, and I think that

Table 2.1

shows nicely how the story played out across the lucky latitudes. Domestication of plants and animals typically began in a region two to three thousand years after cultivation had begun, and walled cities, godlike kings, pyramid-shaped monuments, writing, and bureaucracy typically made their appearance three to four thousand years after domestication (around 2800

B.C.

in what is now Pakistan, 1900

B.C.

in China, and 200

B.C.

in Peru and Mexico).

Table 2.1. Caging and the evolution of military affairs, 10,000â1

B.C.

Military developments are in italics and social ones in roman type. The lines linking development are there purely to make the stages clearer, not to imply links between areas.

Table 2.1

also reveals that developments tended to cluster, showing up in packages. Within the Old World, that was very much the case with the invention of bronze arms and armor. This, the second revolutionary change within the broader evolution of military affairs, generally arrived at roughly the same time as fortifications, cities, and governments. Craftsmen in southwest Asia had begun tinkering with copper, making pretty ornaments, as early as 7000

B.C.

(just five hundred years after domestication really got going), although it was not until about 3300

B.C.

that they learned to make real bronze, mixing copper with tin or arsenic to produce metal hard enough to be useful for arms and armor. Bronzeworking took off in the Fertile Crescent right around the time Leviathan really got going in Uruk. There was probably a connection: bronze also appears in South and East Asia right at the same time as cities and states. (The story was rather different in the Americas, and I will come back to it in

Chapter 3

.)

Using metal on the battlefield seems to have led directly into a third revolution, which once again happened earliest in the Fertile Crescent. It is one thing to have a spear with a bronze point, but it is another altogether to have the intestinal fortitude to walk right up to someone and stick it in him, especially while he and hundreds of his friends are trying to stick their spears into you. Getting the most out of metal called for the invention of military discipline, the art of persuading soldiers to stand their ground and follow orders.

This was arguably the most important of all the ancient revolutions in military affairs. A disciplined army is as different from an undisciplined rabble as the Thrilla in Manila

8

is from two drunks mauling each other in a bar. Soldiers who will close and kill when told to or storm high walls despite boiling oil, falling rocks, and showers of arrows will usually beat those who will not. The evolution of somewhat-reliable command and control, formations that would maneuver more or less as ordered, and men who would usually do what they were told changed everything.

Unfortunately, archaeologists cannot dig discipline up. But even though actual evidence for disciplined troops only appears several centuries later, it seems logical to suspect that they in fact began appearing around the same time as centralized governments and that it was at this point (around

3300

B.C.

in the Fertile Crescent, 2800

B.C.

in the Indus Valley, and 1900

B.C.

in China) that wars began to be settled by pitched battles as much as by raids and sieges. Persuading young men to follow orders in life-threatening situations was one of Leviathan's first great achievementsâeven if, thanks to the lack of hard data, just how prehistoric chiefs did it remains among the least-understood questions in archaeology.

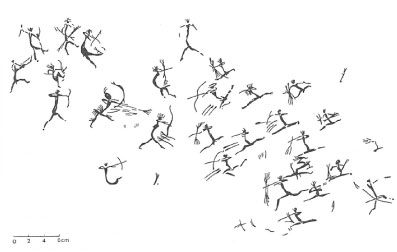

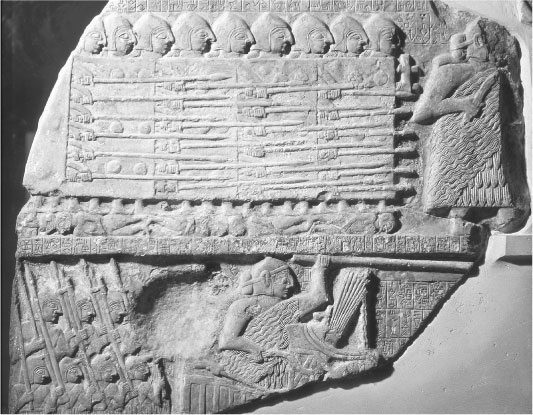

The first tangible evidence comes from art. Stone Age cave paintings, some of them as much as ten thousand years old, regularly represent gaggles of men firing arrows and tossing spears at each other (

Figure 2.5

), but the Vulture Stele (

Figure 2.6

), a Sumerian limestone relief carved around 2450

B.C.

, is very different. It shows dense, apparently disciplined ranks of infantrymen with helmets, spears, and large shields, led by King Eannatum of Lagash. The men of Lagash are trampling on dead enemies, and an accompanying inscription says that Eannatum had won a pitched battle against the city of Umma, which had occupied some of Lagash's farmland. Eannatum subsequently incorporated Umma and much of the rest of Sumer into his kingdom.

Figure 2.5. Crying havoc: chaotic fighting in a prehistoric cave painting from Los Dogues rock shelter in Spain, dating between 10,000 and 5000

B.C.

Figure 2.6. The birth of discipline: this relief carving, known as the Vulture Stele and made at Lagash (in what is now Iraq) around 2450

B.C.

, is the oldest known representation of soldiers drawn up in regular ranks.

Sumerians apparently instilled enough discipline and esprit de corps into their fighting men to settle wars with decisive battles, getting up close regardless of the risk, rather than raiding and running away in the time-honored tradition. In the 2330s, King Sargon of Akkad could even boast of the “5,400 men I made to eat before me each day,” apparently referring to a standing army. His subjects provided food, wool, and weapons so his troops could train full-time.

Wild warriors were being turned into disciplined soldiers. Modern

military professionals have elevated loyalty, honor, and duty into cardinal virtues, far removed from the humdrum selfishness of civilian life, and while the discipline of Sargon's soldiers would probably not have impressed Caesar's centurions, the kind of man who would die before disgracing his regiment probably made his first tentative appearance in third-millennium Sumer and Akkad.

The results are very clear. Akkad conquered most of what is now Iraq, winning battles against Lagash, Ur, and Umma and pulling down their walls. Sargon set up governors, fortified Syria, and campaigned as far as the Caucasus and the Mediterranean. His grandson even crossed the Persian Gulf, where, an inscription says, “the cities on the other side of the sea, thirty-two, combined for the battle. But he was victorious and conquered their cities, kill[ing] their princes.”

Like Rome two thousand years later, Sargon's city of Akkad went on to grow rich trading with India, and if the Indus Valley did not have armies with some kind of discipline before 2300

B.C.

, it probably learned of them

now. It has proved particularly difficult, though, to document the rise of such armies in third-millennium South Asia. In fact, the bottom of

Table 2.1

reveals that something rather more complicated was going on here. In the third millennium

B.C.

, the Indus Valley had been the second region in the world to come up with cities, governments, fortifications, and bronze weapons, several centuries behind the Fertile Crescent but several centuries ahead of East Asia. By the first millennium

B.C.

, though, South Asia had fallen into third place, well behind East Asia.

In a superficial sense, we know what happened: Indus Valley civilization collapsed around 1900

B.C.

Its cities were abandoned, and people turned their backs on Leviathan, shattering the apparently smooth progression in

Table 2.1

. Nearly a thousand years would pass before cities and governments would reappear in South Asia, this time in the plains of the Ganges rather than the Indus, and by then China, which experienced no such collapse, had pulled ahead.

What we don't know is

why

Indus civilization collapsed. We cannot (yet) read the few texts that have survived, and given the continuing challenges involved in excavating in Pakistan, the evidence remains thin. In the late 1940s, when former military men ruled the archaeological roost, it was generally agreed that Aryan invaders, described in later Indian epics, had destroyed the Indus cities. By the 1980s, at the height of

Coming of

Age-ism, the general agreement was that they had not, and new culpritsâclimate change, internal rebellions, economic breakdownâwere fingered. In the enlightened 2010s, we have to admit that we simply do not know.