War of the Whales (27 page)

Authors: Joshua Horwitz

14

Acoustic Storm

There was a big unspoken X factor in the Secretary’s decision to temporarily shut down deep-water sonar exercises. What everyone on the conference call knew—that didn’t even bear mentioning because it was so obvious—was that for the past six years, Joel Reynolds had been hounding the Navy over its planned deployment of Low Frequency Active (LFA) sonar. Ever since the ship shock trial, he’ d been digging into the Navy’s underwater sound projects, including its classified low-frequency sonar program.

The Bahamas stranding couldn’t have come at a worse time for the team at ONR, led by Bob Gisiner, that had been shepherding the long-range, low-frequency sonar system through its permit application with Fisheries. Low Frequency Active sonar wasn’t being tested in the Bahamas, by either ONR or the fleet. But the publicity surrounding the mass stranding of whales might plant unwelcome doubts about the system’s safety in the minds of the public, of regulators at Fisheries, and of any judge who might hear a lawsuit to block its deployment.

No one on the conference call had more invested in Low Frequency Active sonar than Admiral Dick Pittenger. He’ d been its godfather back in the late 1980s, and ever since, he’ d tracked its growing pains and troubled adolescence. Now that it was finally ready for deployment—and just when the Navy needed to make the case that LFA sonar posed no threat to marine mammals—17 whales had washed ashore in the Bahamas during exercises.

Some had argued, both inside and outside the Navy, that ten years after the end of the Cold War, LFA sonar had outlived its original purpose of detecting Soviet submarines at long range. But Pittenger knew from a naval career devoted to antisubmarine warfare that the race for technological advantage has no finish line. You always have to be innovating and training for the next war, the next enemy. He’ d been right there in the thick of it the last time the US Navy got caught napping.

• • •

As soon as the SOSUS listening network had been installed in the Pacific and Atlantic basins, in the early 1960s, naval strategists began worrying about its inevitable obsolescence. Soviet submarines were still noisy enough to detect with passive listening sonar. But someday they would become quiet enough to render SOSUS useless and America defenseless against submarine-launched missiles.

By the mid-1960s, even before Balcomb was tracking Soviet subs from the Pacific Beach SOSUS station, the Office of Naval Research had conceived of a countermeasure. When the day arrived that Soviet submarines became too quiet to be heard by wiretapping the deep sound channel, the US Navy would echolocate them with

active

sonar.

active

sonar.

The first attempt at a long-range, active sonar system—code-named Project Artemis—ended in failure.

1

The massive array of underwater sound transmitters and receivers that the Navy anchored in the waters off Bermuda was doomed by the primitive state of signal processing in the 1960s, which severely limited Artemis’ ability to identify objects hundreds of miles from its sound source. The physical and biological clutter between the transmitters and their distant target made it impossible to read an echo cleanly. After six years of pummeling the oceans with high-intensity sound, the Navy dismantled Artemis and went back to the drawing board.

1

The massive array of underwater sound transmitters and receivers that the Navy anchored in the waters off Bermuda was doomed by the primitive state of signal processing in the 1960s, which severely limited Artemis’ ability to identify objects hundreds of miles from its sound source. The physical and biological clutter between the transmitters and their distant target made it impossible to read an echo cleanly. After six years of pummeling the oceans with high-intensity sound, the Navy dismantled Artemis and went back to the drawing board.

By the mid-1970s, the Navy faced a genuine crisis in long-range submarine detection. As each generation of Soviet submarines became progressively quieter, the US acoustic advantage gradually eroded. Soon Soviet submarines would be silent to SOSUS. In 1974 the Navy convened its first “Workshop on Low-Frequency Sound” at Woods Hole with the express mission of replacing the passive sonar surveillance of SOSUS with a long-distance

active

system. Since low-frequency sound waves traveled much farther through the ocean, low frequency was the starting point for the development of long-range, “over-the-horizon” submarine detection.

active

system. Since low-frequency sound waves traveled much farther through the ocean, low frequency was the starting point for the development of long-range, “over-the-horizon” submarine detection.

It wasn’t until the autumn of 1985 that the Navy finally figured out how the Soviets had been able to build submarines quiet enough to test the limits of SOSUS detection. Two low-ranking Navy communications officers—John Walker Jr. and Jerry Whitworth—were arrested and convicted of having sold top-secret naval intelligence to the Soviets over an 18-year period, compromising both the SOSUS listening system and the US Navy’s submarine-quieting technology. The Walker-Whitworth case proved to be America’s most damaging intelligence breach of the Cold War and its highest-profile espionage trial since Ethel and Julius Rosenberg’s convictions and executions in the early 1950s.

2

2

A few months after the trial, the Soviet navy launched its new Akula-class nuclear-powered attack submarines. The aptly named Akula, Russian for “shark,” was the quietest Soviet hunter-killer sub to ever roam the oceans—and it was undetectable by SOSUS. Three decades of SOSUS-enabled domination in antisubmarine warfare had ended. The era of active sonar was at hand.

In the wake of the Walker-Whitworth trial, Admiral Dick Pittenger was promoted from chief of staff of the US Naval Forces in Europe to director of the Antisubmarine Warfare Division at the Pentagon. His urgent mission was to transform the acoustic storm of high-intensity active sonar into a precise tool for long-range submarine detection. For help, he turned to the Navy’s foremost stormcaster: a playful pixie of a man with an incalculably high IQ.

• • •

Walter Munk had earned his reputation as a wizard of underwater weather forecasting during World War II. Having recently emigrated from Vienna, Austria, Munk was a 24-year-old graduate student at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla when America joined the war in 1941. Toiling in a bunker beneath the Pentagon with only weather maps, sea charts, and a slide rule as his guides, Munk was able to track storm-driven waves across the entire Atlantic Ocean and accurately forecast surf conditions weeks in advance of the Allies’ amphibious landings on the beaches of North Africa and Sicily.

3

3

Munk’s highest-stakes prediction of the war was forecasting a 16-hour lull in an Atlantic Ocean storm between June 5 and 7, 1944. At 6:30 a.m. on June 6, the supreme commander of the Allied forces, US general Dwight D. Eisenhower, launched the D-day landing along the beaches of Normandy, France, in maneuverable two- to three-foot surf. The assault caught the Germans by surprise, and the liberation of Europe had begun. Munk went on to successfully forecast surf conditions for American landings on the Pacific islands of Saipan, Guam, Tinian, Palau, the Philippines, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa.

Though Munk’s contributions to the war effort went unheralded in public,

4

the Navy was determined to keep its brightest young oceanographer under contract. In 1946 the Office of Naval Research sent Munk on a world tour of Navy-funded research voyages: first aboard a Navy icebreaker to study submarine operations in the Arctic, and then to the South Pacific to observe the underwater impact of the atom and hydrogen bomb tests.

4

the Navy was determined to keep its brightest young oceanographer under contract. In 1946 the Office of Naval Research sent Munk on a world tour of Navy-funded research voyages: first aboard a Navy icebreaker to study submarine operations in the Arctic, and then to the South Pacific to observe the underwater impact of the atom and hydrogen bomb tests.

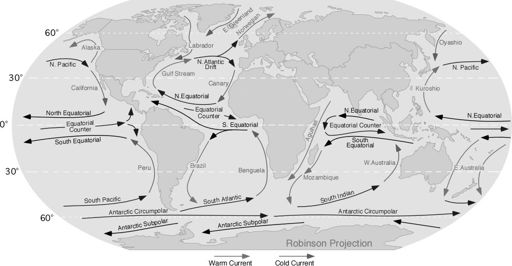

Over the course of the Cold War, Munk divided his time between conducting his own research at Scripps and problem solving for the Navy. Like all inveterate explorers, Munk was drawn to virgin territory, and the ONR was happy to let him follow his curiosity into uncharted waters. Munk’s genius lay in seeing the order amid the complexity and seeming chaos of the oceans. He was the first oceanographer to recognize that the interlocking network of internal ocean currents that circulated throughout the globe’s oceans were driven by the wind’s force against the countless tiny surface ripples. He called them “wind-driven gyres.”

5

And when he delved beneath the ocean surface, Munk discovered underwater storm systems directly analogous to those in the atmosphere. His insights turned oceanography on its head and reframed the Navy’s thinking about how best to track Soviet submarines.

5

And when he delved beneath the ocean surface, Munk discovered underwater storm systems directly analogous to those in the atmosphere. His insights turned oceanography on its head and reframed the Navy’s thinking about how best to track Soviet submarines.

In 1961 Munk was invited to become the first nonphysicist member of “the Jasons,” the Pentagon’s newly formed, top-secret think tank.

6

Conceived as the Cold War’s equivalent of the Manhattan Project, the Jasons were a fraternity of academic scientists who spent their summers working in small groups to crack puzzles posed by American military strategists.

*

The group was christened by Mildred Goldberger, the wife of one of its founding physicists, to evoke Jason and the Argonauts in search of the Golden Fleece.

7

6

Conceived as the Cold War’s equivalent of the Manhattan Project, the Jasons were a fraternity of academic scientists who spent their summers working in small groups to crack puzzles posed by American military strategists.

*

The group was christened by Mildred Goldberger, the wife of one of its founding physicists, to evoke Jason and the Argonauts in search of the Golden Fleece.

7

Walter Munk’s wind-driven gyres.

As the czar of Antisubmarine Warfare Planning, Admiral Pittenger consulted frequently with Munk and his “Jason Navy” on how to use low-frequency sound to light up the dark ocean depths.

8

At a Jason summer study in the late 1970s, Munk proposed a novel method for using low-frequency sound to surveil the ocean. He called it “ocean acoustic tomography” to evoke the recent advent of computerized tomography, or CT, scanning—the same imaging technology that Darlene Ketten would later use to scan whale ears at Johns Hopkins.

9

8

At a Jason summer study in the late 1970s, Munk proposed a novel method for using low-frequency sound to surveil the ocean. He called it “ocean acoustic tomography” to evoke the recent advent of computerized tomography, or CT, scanning—the same imaging technology that Darlene Ketten would later use to scan whale ears at Johns Hopkins.

9

Pittenger immediately recognized the potential value of acoustic tomography to antisubmarine warfare. He funded regional demonstration projects for acoustic tomography and granted Munk access to SOSUS listening arrays to use as receivers. Perhaps to cement his already close connection to Navy research, in 1984 Munk was awarded a lifetime appointment as the first Secretary of the Navy/Chief of Naval Operations Chair in Oceanography at Scripps.

It was through a Jason study project that Munk’s career-long fascination with marine weather forecasting found a new focus: global warming. At the request of the US Energy Department, Munk forecast how carbon dioxide loads around the world would affect climate change.

10

Based on his research, Munk was convinced that the atmosphere was heating up. But the question remained: How quickly was the climate changing, and how could it be measured?

10

Based on his research, Munk was convinced that the atmosphere was heating up. But the question remained: How quickly was the climate changing, and how could it be measured?

Measuring temperature change in the atmosphere was difficult with so many variables of latitudes, seasons, and weather patterns. Munk reasoned that since the oceans absorb most of the heat in the atmosphere, taking the ocean’s temperature would be the most reliable test of whether the planet was running a fever. But because of the ocean’s own variable weather patterns, dipping thermometers over the sides of ships would measure temperature only in specific locations.

When Munk finally seized on the best way to measure the ocean’s temperature, he was delighted by the simplicity of his solution. Best of all, he conceived of a single experiment to test both climate change

and

acoustic tomography on a global scale. All he needed was the right equipment and enough money to deploy it across five oceans and seven continents. It would require a high-energy sound source and more than a dozen receivers stationed around the world. He’ d have to broadcast the sound signal over a period of years, so it would be expensive to maintain. Even a feasibility test would be costly.

and

acoustic tomography on a global scale. All he needed was the right equipment and enough money to deploy it across five oceans and seven continents. It would require a high-energy sound source and more than a dozen receivers stationed around the world. He’ d have to broadcast the sound signal over a period of years, so it would be expensive to maintain. Even a feasibility test would be costly.

Fortunately, he knew the admiral who could deliver on all fronts.

• • •

By 1989, Dick Pittenger had moved from the Pentagon to the Naval Observatory to become Oceanographer of the Navy. Pittenger was delighted to get Walter Munk’s invitation for a drink at the Cosmos Club. Though he considered Walter a friend, he understood that it was a business meeting. Pittenger expected that he’ d be pitched a wonderful and, most likely, wonderfully expensive idea. Though he no longer had a hefty R&D budget at his disposal, Pittenger was still well connected where it counted: at ONR, at the Pentagon, and on Capitol Hill.

Housed in an elegant nineteenth-century mansion, with its membership reserved for distinguished scientists and statesmen, the Cosmos Club was Munk’s home base in Washington and his favorite venue for proposing projects to congressmen and admirals. When Pittenger found him inside the club’s wood-paneled bar, Munk was absorbed in arranging sugar packets into a starburst pattern. His elfin figure bent over the carefully arranged sugar packets, and his feet dangled in the air, not quite reaching the floor. Perhaps because of Munk’s imposing intellectual stature, it always surprised Pittenger to see how small and boyish he appeared in person.

Other books

Forbidden (Devil's Sons Motorcycle Club Book 1) by Thomas, Kathryn

Acadia Song 04 - The Distant Beacon by Oke, Janette, Bunn, T Davis

Murder in the Green by Lesley Cookman

Charles the King by Evelyn Anthony

Far Country by Malone, Karen

Freeing Alex by Sarah Elizabeth Ashley

Lady Amelia's Mess and a Half by Samantha Grace

The Last of the Spirits by Chris Priestley

Much Ado about the Shrew by May, Elizabeth