Wandering Greeks (24 page)

Authors: Robert Garland

High-Profile Exiles

Narratives of politicians on the run captured the popular imagination. One of the most exciting has to do with Themistocles, architect of the Greek naval victory at Salamis. No doubt the fugitive had recounted it in later years himself, with of course appropriate embellishments (see

map 7

). Under the pronouncement of ostracism from the Athenian Assembly in ca. 472, Themistocles first settled in Argos, where he had powerful friends. From there he “visited” other places in the Peloponnese. The Spartans, who hated the Argives, found his presence irksome and insulting, and they persuaded the Athenians to condemn him to death on the trumped-up charge of conspiring with the Persians. Accordingly a posse of Athenians teamed up with some Spartans with orders to “seize him wherever they might find him” (Thuc.1.135.3).

Catching wind of their approach, Themistocles fled to Corcyra, where he expected to receive a warm reception, since he had done good service to the islanders in the past. The Corcyreans were fearful of antagonizing both Athens and Sparta, however, so they immediately sent him back to the mainland. He sought refuge with Admetus, king of the Molossians, despite the fact that the two of them had not previously

been on good terms. When his pursuers turned up at Admetus's palace soon afterward, the king ordered them to leave (see

chapter 7

).

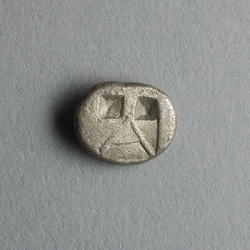

FIGURE 13

Silver

triôbolon

(coin worth three obols) from Argos, ca. 490â70. The obverse depicts the forepart of a wolf, the symbol of Apollo Lykeios, who was worshipped in Argos. On the reverse is the letter “A” with two incuse (that is, recessed) squares containing pyramidal sections. Argos's king Pheidon, who reigned some time between the eighth to sixth centuries, was credited, improbably, with being the first to strike coins in Greece. The

polis

claimed to be “the longest continuous occupation of any place in Greece” (Cartledge 2009, 38). It was a stable democracy throughout the classical period, apart from two brief periods when the oligarchs seized control.

Themistocles then journeyed to Pydna, a coastal town in Macedonia, where he was hospitably received by its king, Alexander. Without revealing his identity he later boarded a merchant vessel bound for the coast of western Asia Minor. As luck would have it, however, the boat ran into a storm and was diverted to the island of Naxos, which was currently under blockade from the Athenian navy. Themistocles proved to be as quick-witted as ever. He immediately revealed his identity to the captain of the vessel, warning him that, if he handed him over to the Athenians, he would claim that the captain had accepted a bribe to take him on board. Themistocles also promised to reward him if he succeeded in making his escape. The latter agreed and a day or so later the boat set sail for Ephesus.

After disembarking, Themistocles journeyed inland toward Persia. By now he had been on the run for about three years. En route he wrote a letter to Artaxerxes I, the Persian king, claiming that he had become a

fugitive because of his friendship for Persia and requesting permission to reside within its borders for the space of a year. The king agreed. However, before presenting himself at court, Themistocles took the sensible precaution of familiarizing himself with the Persian language and customs so as to make the best possible impression on his host. The strategy worked to perfection, and Themistocles came in time to be held “in higher honor than any Greek before or since” (Thuc. 1.138.2). The king appointed him governor of Magnesia, where he resided until his death. He remained at heart an Athenian, however. When he died, his friends, in accordance with his wishes, succeeded in smuggling his bones back to Attica, where they buried them secretly, since it was forbidden to bury in Attic soil an outlaw who had been condemned for treason.

MAP 7

Themistocles' flight to Persia.

The narrative of Alcibiades'flight is equally thrilling and contains even more twists and turns. In 415, shortly before the departure of the Sicilian

Expedition to which he had been appointed as one of its three generals, he was accused of being implicated in the mutilation of the hermsâstone pillars of Hermes with carved heads and erect penises that stood at street cornersâand of profaning the Eleusinian Mysteries. His request to be put on trial before he sailed was denied and he was ordered to proceed forthwith to Sicily, together with his colleagues, Nicias and Lamachus. Soon after his arrival in Sicily, however, he was recalled to Athens at the insistence of his accusers. Alcibiades was taken on board ship but succeeded in escaping from his warders when they docked at Thurii. Very likely some of the ship's crew were sympathetic to his cause or alternatively were under the spell of his magnetic personality. He then fled via Elis to Sparta, where he proceeded to ingratiate himself with his hosts. The Athenians condemned him and his associates to death

in absentia

, whereupon he memorably remarked, “I'll show them that I'm still alive” (Plu.

Alc

. 22.2). They also confiscated his property and placed him under a curse (Thuc. 6.61.4â7; Isoc. 16.9).

Alcibiades now proceeded to give military advice to the enemy that was highly damaging to Athens. In fact his defection to the Spartans is merely the most spectacular example of what was a very common practice among political exilesâthe exaction of revenge on one's native land for being declared a traitor. He urged his hosts to fortify Decelea in the north of Attica, which now became a haven for runaway slaves a mere 13 miles from Athens. “This above all brought about the ruin and destruction of his city,” Plutarch (

Alc

. 23.2) caustically observed. But though Alcibiades won the goodwill of the Spartans in the short term by adapting to their austere way of life, they eventually began to suspect his loyalty and he was compelled to flee again, this time to Ionia. It certainly did not help his relationship with them that he was accused of having seduced Timaea, the wife of King Agis, when the latter was stationed at Decelea.

He now began to intrigue with the Persians. In 412/11 he managed to secure a position as advisor at the court of the satrap Tissaphernes in Sardis, where, in an attempt to bring about his recall, he tried to secure the support of Persia on Athens's behalf. Tissaphernes fell under the spell of Alcibiades' personality, but in the end the hope of acquiring

aid came to nothing (Thuc. 8.52; Plu.

Alc.

24.3â25.2). Shortly afterward, Alcibiades, along with a number of other exiles, was recalled by the Five Thousand, Athens's government at the time (Thuc. 8.97.3). He decided not to accept their offer, however, fearing that if he did, he would again have to face criminal charges. Instead he was appointed general of the Athenian fleet at Samos. It was in this capacity that he now won a significant naval victory at Cyzicus in 410. Finally convinced that he had nothing further to fear from his fellow-citizens, Alcibiades returned to Athens in 407. His most memorable accomplishment was the restoration of the procession to Eleusis that took place on the final day of the major annual celebration of the Eleusinian Mysteries. Ironically, it was the Spartan occupation of Decelea that had made the overland journey extremely dangerous for initiates, and so the Athenians had temporarily suspended the procession and replaced it with a voyage along the coast.

Alcibiades was now formally cleared of the charges that had been lodged against him eight years previously (Xen.

Hell.

1.4.12). Even so, he remained a highly controversial figure. His enemies continued to scheme against him and eventually succeeded in depriving him of his generalship. So in 406 he threw in the towel and withdrew to the Thracian Chersonese. The following year he made an appearance at the Athenian encampment in the Hellespont to inform the generals that he was on good terms with the Thracians and could secure their services on Athens's behalf. They rebuffed his offer and the Athenian fleet was heavily defeated at Aegospotami soon afterward (Xen.

Hell

. 2.1.25â6; D.S. 13.105.3â4). Alcibiades fled yet again, this time to the court of the Persian satrap Pharnabazus in Hellespontine Phrygia. Acting on the advice of the Thirty Tyrants and of the Spartans, Pharnabazus had him assassinated in 404/3.

Both narratives are extraordinarily rich in detail. They not only indicate a deep fascination with high-profile fugitives but also testify to the existence of a world of possibilities for enterprising individuals on the run that extended beyond the confines of the Greek-speaking world. As the double-dealing of Alcibiades indicates, moreover, exile could have profound, even catastrophic consequences for the exile's city-state, if the

exile placed his expertise at the service of the enemy. But whereas high-profile political fugitives might have found a warm welcome abroad, nonpolitical exiles of no social rank were exposed to dangers and threats wherever they went. Those most at risk were the ones who were guilty of the most notorious crimes. One such was a Phocian called Phalaecus, who had pillaged the sanctuary at Delphi and who in Diodorus's words “passed his long life wandering about in considerable fear and danger ⦠and became famous because of his misfortune” (16.61.3).

Runaway Slaves

We have no means of knowing what percentage of the servile population chose flight with all its attendant dangers in preference to slavery. Though the Athenians occasionally employed

drapetagôgoi

(runaway-catchers), it is likely that they hired them on a strictly temporary basis (Ath.

Deipn

. 4.161d). Sometimes, too, the slave-owner would set off in hot pursuit of his own

drapetês

(runaway) (Dem. 53.6).

Papyri from Ptolemaic Egypt indicate that in the hellenistic period and no doubt earlier the risk of a slave taking flight was sufficiently common for vendors to make it their practice to stipulate on a bill of sale that the merchandise they were selling “was neither a wanderer nor liable to flee nor susceptible to epilepsy” (

PTurner

22, dated 142 BCE). Other papyri of similar date announce rewards for their capture. One of these runaways was a Syrian called Hermon, who is described in great detail as follows:

About 18 years old, of medium stature, beardless, with good legs, a dimple on the chin, a mole by the left side of the nose, a scar above the left corner of the mouth, tattooed on the right wrist with two barbarian letters. He has taken with him three

octadrachmae

of coined gold, ten pearls, an iron ring on which an oil flask and strigils are represented, and is wearing a cloak and a loincloth. Whoever brings back this slave shall receive 3 talents of copper. If he points him out in a shrine [where he is presumably seeking asylum],

2

talents. If he points him out in the household of a substantial and actionable

man [who has presumably taken him in as a slave], 5 talents (

PPar

. 10 dated 156 BCE, adapted from the translation of Hunt and Edgar [1963, no. 234]).

I sincerely hope Hermon evaded his captors.

Since we have no testimonia from runaways themselves, we can only speculate as to what compulsion would have driven them to abscond. Other than in time of war, they seem for the most part to have fled singly, the overwhelming majority of them no doubt being males. If they were caught, it is possible that they were branded like livestock, either on the forehead or on the shoulder, to indicate that they were a flight risk. Though escape from a harsh master or mistress would seem to be the primary motivation for absconding, it may be that the indignity of the institution was insufferable to some. We know nothing about how a runaway might have identified potential harborers or how he selected a final destination. We never hear of the equivalent of an underground railway. The obvious recourse would have been to merge into the background and pretend to be free (Lys. 23.7). Even if a slave escaped abroad, however, it would have been difficult for him to remain at liberty, since foreigners were an inevitable source of curiosity, even in an accommodating

polis

like Athens. Some, therefore, as intimated by the papyrus just quoted, probably threw themselves on the mercy of another slave-owner in the hope that they would receive better treatment. Others might have committed serious crimes while on the run, simply in order to stay alive. The one advantage that slaves in the Greek world had over African-American slaves in the antebellum South was that they did not conform to a single racial group and therefore could not be automatically identified. In fact [Xenophon], aka the Old Oligarch, goes further and claims that the clothing and general appearance of slaves made it impossible to distinguish them from free on the streets of Athens (

Ath. Pol

. 1.10).