Wallach's Interpretation of Diagnostic Tests: Pathways to Arriving at a Clinical Diagnosis (640 page)

Authors: Mary A. Williamson Mt(ascp) Phd,L. Michael Snyder Md

CROSSMATCH

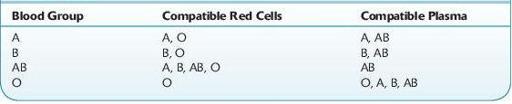

After a type and screen is completed, an appropriate blood product can be selected to transfuse the patient. Ideally, ABO identical blood products should be transfused, but due to inventory management constraints, often ABO compatible (but not ABO identical) products are issued for transfusion. Table

15-2

reviews the type of red cells and plasma that are compatible with each of the ABO blood groups.

TABLE 15–2. Blood Products That are Compatible with Each ABO Blood Group

Plasma, platelets, and cryoprecipitate can be transfused without a crossmatch. However, for RBC transfusion, each unit of red cells should be crossmatched with the recipient’s plasma prior to transfusion. The type of crossmatch necessary depends on whether the patient’s antibody screen is positive or negative.

If the patient’s antibody screen is negative, generally an immediate spin crossmatch is performed by simply mixing the red cells selected for transfusion with the patient’s plasma and checking for agglutination after centrifugation. An immediate spin crossmatch is essentially a second check of the donor and recipient’s ABO compatibility as agglutination will be seen if the patient’s plasma has ABO antibodies to cognate antigens on the red cells selected for transfusion. In some institutions, patients who have a negative antibody screen may be eligible for an “electronic crossmatch” if the institution has validated the blood bank information/computer system to not allow an incompatible blood product to be issued to the patient. If the patient had a positive antibody screen, a complete crossmatch using AHG is appropriate. Many clinically significant non-ABO alloantibodies are IgG antibodies and will not result in agglutination unless AHG is added to the suspension of red cells and plasma. Thus, patients who have a positive antibody screen should have the crossmatch performed by incubating the patient’s plasma and donor red cells at body temperature followed by addition of AHG.

The sample of blood used to perform the crossmatch (as well as the type and screen) must be recently acquired from the patient if the patient has been recently transfused or pregnant. This is necessary because the patient may produce an antibody to a RBC antigen within a few days after being exposed to allogeneic red cells. Generally, a sample should not be more than 3 days old if the patient has been recently transfused or pregnant, but a sample drawn up to 2 weeks prior to transfusion is acceptable if the patient has not had any recent exposure to blood. It is also important to review the blood bank history to prevent the transfusion of RBCs that may have antigens that the patient previously had antibodies to. In these patients, the antibody titer may decrease in strength to below detectable levels, but subsequent exposure to the antigen can result in brisk antibody production and a delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction. Unlike RBC transfusion, transfusion of other blood products does not require a recent sample because selection is based on the patient’s blood type, and a crossmatch does not need to be performed.

TRANSFUSION OF BLOOD PRODUCTS

Transfusion of blood products carries significant risks. Thus, prior to any transfusions, the risks and benefits should be carefully assessed and blood products should be provided to the patient only if the benefits outweigh the risks. Today, transfusion of whole blood is exceedingly rare in the United States. Patients are usually transfused with the specific blood component that is required (e.g., packed red cells, plasma, platelets, or cryoprecipitate).

RED CELL TRANSFUSION

The goal of red cell transfusion is to increase oxygen delivery to tissues when necessary. Red cell transfusion is appropriate for the treatment of anemia if it will ameliorate symptoms of anemia or aid in correcting or preventing the adverse physiologic consequences of anemia. Most patients will tolerate a loss of approximately 50% of their circulating hemoglobin before they start to experience significant consequences due to acute anemia. In acute blood loss, symptoms due to hypovolemia are usually seen before symptoms due to anemia. In chronically anemic patients (patients who become anemic over weeks or months), compensatory mechanisms allow patients to tolerate lower hemoglobin levels than patients who become acutely anemic. Considering the many variables involved, it is often challenging to determine whether tissue ischemia exists and whether it will be alleviated with red cell transfusion.

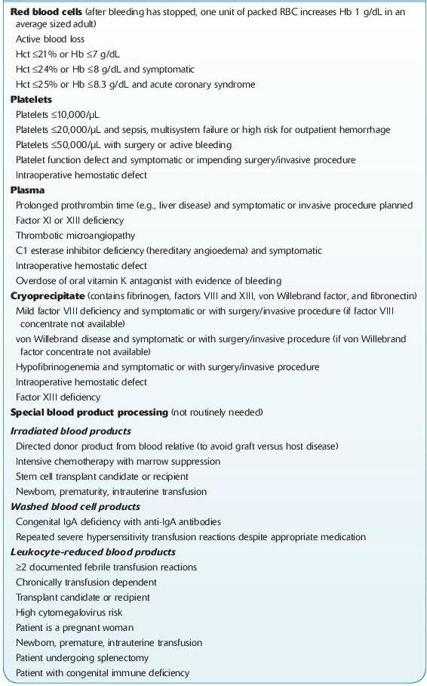

Who Should Be Suspected?

There is a significant variation in RBC transfusion practices between institutions. Most studies that have audited transfusion of blood products have reported that there was unnecessary transfusion of patients and there is a trend toward more conservative hemoglobin transfusion triggers. Authorities in TM agree that most patients with a hemoglobin of <6 g/dL will need red cell transfusion and most patients with a hemoglobin of >10 g/dL will not require red cell transfusion. There is also general agreement that within this range, the transfusion of blood products needs to be individualized to the patient. At the author’s institution, a trigger of a hemoglobin of 7 g/dL is used for most hospitalized patients with the notable exception of patients with unstable cardiac disease (see Table

15-3

).

TABLE 15–3. Common Indications for Blood Product Transfusion and Special Processing

PLASMA TRANSFUSION

The previous practice of using plasma as a volume expander has largely become extinct. Today, plasma is almost always transfused to patients due to a deficiency of one or more proteins present in normal plasma. The proteins that are most commonly repleted are coagulation factors. Other deficient proteins that may be repleted with plasma transfusion include ADAMTS 13 in patients with TTP and complement factors in patients with HUS.

Who Should Be Suspected?

Despite the most common indication for plasma transfusion being the treatment of coagulopathy, there are no clear guidelines for the appropriate use of plasma in this setting. Thus, very often plasma is transfused unnecessarily to patients who do not benefit from it.

A more proactive approach in regard to plasma transfusion is appropriate in bleeding patients who require massive transfusion of blood products. In such patients, if coagulopathy develops, it may result in excessive bleeding that can be life threatening and it may be extremely difficult to correct a severe coagulopathy. These patients have multiple factors contributing to the coagulopathy including dysfunction of the enzymes of the coagulation cascade (due to hypothermia and acidosis) and consumption of coagulation factors due to DIC.

Considerations

Several types of plasma products are available for transfusion. These include fresh frozen plasma (FFP), frozen plasma 24 (FP24), and thawed plasma (TP). FFP is plasma that has been separated from a whole blood collection and put into a freezer within 8 hours of collection. FP 24 is plasma that has been placed in the freezer within 24 hours of collection. Both of these products can be kept frozen up to 1 year; however, once thawed, they must be used within 24 hours. Thawed plasma is FFP or FP24 that has been relabeled as “thawed plasma” and now can be used for up to 5 days after thawing. The concentration of the majority of coagulation factors does not vary significantly among FFP, FP24, and TP with the exception of factor V and factor VIII. FP24 and TP have lower concentrations of factor V and factor VIII as these two factors have the shortest in vitro half-life. However, factor 5 deficiency is rare, and factor 8 is an acute-phase reactant that is often elevated in patients requiring plasma transfusion. Most often, the vitamin K–dependent factors (II, VII, IX, and X) are the factors that need to be replaced in order to correct coagulopathy. These factors are stable at refrigerator temperatures and not significantly decreased in FP24 or TP.

Laboratory Findings