Waking the Dead (54 page)

I looked for her. But it was not a real search because I knew I would not find her. She had probably left hours ago. Before the day broke. I ran into a member of the Capitol police. He had no idea who I was, but I somehow communicated to him that I was Congressman Pierce. He asked me if I’d been in the building all night and I said I had. He didn’t seem particularly surprised, but he did make it a point to walk with me as I went back to my office. He was a well-built black man. He wore thick eyeglasses that he kept snug on his flat, smooth face with a black elastic band. When we reached my office, the door was wide open.

“See you’re just moving in,” he said, looking over my shoulder and into the mess.

I nodded yes.

“Next time you spend the night,” he said, smiling, “best you let us know so we know you’re here. You don’t want to make us look bad, do you?”

I walked into my office and closed the door behind me. I felt cold. I rolled my sleeves down, buttoned them, and found my jacket and put it on. I went to the bathroom and then drank a cup of tap water. I just wandered around, touching things, looking at the boxes on the floor. Suddenly, my heart began to race but then it slowed down to its normal beat and I felt very strange but in control of myself. I went back to the office where I had spent the night with her and looked at the floor, wishing it had been earth and the imprint of our bodies had been there for me to see.The window behind my desk was brightening and it cast a slanted box of light onto the desk. I touched the wood. It was smooth. Someone had waxed it recently. I felt a spasm of emotion and I stopped in my tracks, letting myself cry if that’s what I wanted. But the feeling could not break the surface of the overwhelming sense of quietness I had just then. I walked around my desk and sat in my chair.

I picked up the phone, but it was so early and there was no one to call. I placed the receiver in its cradle and then reached for the box marked

CORRESPONDENCE

that Dina Jensen had left for me. It was a gray and white cardboard box, secured by a strip of masking tape. I peeled the tape off and opened the box. Inside, there were fifty or so letters, bunched in little groups by paper clips—some system Dina had worked out, I guessed. Attached to the front-most group was a handwritten note from Dina. “Congressman Pierce—These came after Mr. Carmichael left and so now they are for you.”

The letters had been opened, probably scanned, and then placed back in their envelopes. I chose one at random, opened it, and read:

Dear Congressman Carmichael,

My son is nineteen years old. He was born with very low birthweight and has never enjoyed good health. Against my wishes, he joined the Army last July. I think it was a very bad thing the Army did to take him. When I got a letter from two doctors stating that Mark’s health was poor and that he was a heart-risk, the man at the Recruiting Station (Sgt. Fred V. Colburn) said he would send these letters to Mark’s Commanding Officer (Capt. E. M. Gomez). Mark is stationed in Hamburg, Germany, and Captain Gomez has not answered any of my letters. I called him international long distance and he would not even come to the phone! In the meanwhile, my son’s health has gotten worse. He has been in the Army hospital with a very high fever and has had a blood transfusion. He is also having chest pains and has lost 24 pounds in the past eight weeks. If someone does not do something, I know as God is my witness that my son will die in the Army. He is all I have but he is very stubborn. No one will listen to me!

Yours truly,

(Mrs.) Laura Morris

Dear Congressman Carmichael,

Can you please send me any information about the rights of adopted children? Please mark the envelope Personal—Top Secret—Do Not Open. If the people here saw what I was doing they would kill me.

Thank you,

Steven Benardi

PS. I don’t know what my Real Name is.

Dear Congressman Carmichael,

Four years ago my best friend Andrew Rosen and I were in Marrakesh, Morocco. It was a vacation trip. Three days before we were due to return home to Chicago, Andy disappeared.The Moroccan police did nothing. In fact, their attitude was very offensive. The American Consulate in Rabat was polite on the phone, but when I went there to speak to someone, no one would see me. And it now has been four years and they have done no more than write a couple of letters. They seem to believe Andrew was involved in something he shouldn’t have been. But I can tell you that Andy was doing nothing wrong. I am a waiter at

the

Blackstone Cafe and I have saved enough money to return to Morocco. If the police and the Embassy will do nothing to find Andy, I feel it is my duty to at least try. (The Rosens have given him up for lost and they don’t seem to be very upset.)

If you will check your files, you will see that I wrote to you regarding Andy Rosen on September 9, 1978, March 1, 1979, June 18, 1979, and November 1, 1979. Although your office has sent notes acknowledging receipt of my letters, I have yet to hear from you, Representative Carmichael. I am planning my trip to Morocco for April 2, 1980, and while I am there will do everything in my power to find Andy and expose the people who have done whatever has been done to him. But I am only one person. My task would be much easier if I could count on some cooperation from Moroccan or American officials. Morocco is an American ally and I know strong words from a U.S. congressman would have a great effect. Please refer back to the letters I have sent you. All of the information about Andy is in them, including photographs, his school records, and statements from the many friends who loved him. If you could lend your name to our efforts, I know our chances of finding him will be greatly increased. If he is alive, he is in a living hell.

Thank you again,

Kevin Ertel

Dear Congressman Pierce,

Congratulations on your election to the United States House of Representatives. I want to say I proudly cast my ballot for you. My name is Samuel K. Smith. I am a retired member of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. I used to live at the Belvedere Apartments on Cottage Grove and 60th Street, but since the fire I am living in a much smaller apartment on Cottage Grove and 54th Street. I am writing you now because I am having a bad problem with my Social Security. When I moved from my apartment after the fire, two of my checks were lost. Then some little crooks got their hands on the checks and cashed them. This caused a big problem with the Social Security and I was brought downtown to their offices and spoken to. When I left I thought it was all worked out, but I was wrong. It has been two months and I have not gotten a check. Also I have not been paid back for the checks that were lost. That makes four months with no Social Security. I have not had money for food. I have taken food out of the garbage in the halls. I have not been able to wash my clothes and I do not have money for bus fare. The people in the Social Security are taking their time. But time is one thing I do not have. I feel I am being treated very unfairly. I can’t live without money. No one can. And this money they are holding from me is mine. I earned it. I have done everything I know how to do to get this problem fixed up. I know you are very busy but if I could come to your office in Washington I would be there right now and I would get down on my knees and take your hand and beg you to please please help me before it is too late.

Scott Spencer is the

New York Times

—bestselling and award-winning author of ten novels, including the National Book Award finalists

Endless Love

(1979) and

A Ship Made of Paper

(2003).

Born in 1945 in Washington, D.C., Spencer moved with his family to the South Side of Chicago at age two. His father, Charles, had been in the army before beginning work in a hot and noisy Chicago steel mill. Charles later wrote and self-published a book titled

Blue Collar

(1978) about the experience. Spencer remembers his childhood as peaceful despite his family’s tight finances and his parents’ concern over the political climate during the McCarthy Era, both of which were kept secret from Spencer at the time. Charles was a dissident in his union and, Spencer remembers, “sometimes feared for his safety and even his life. There were mornings when he checked under the hood of his car for a bomb before igniting the engine.” The far South Side of Chicago was at the time the set of atrocious racial violence, which Spencer’s parents steadfastly resisted, adding to the home’s sense of peril and purpose.

Spencer was an avid reader from an early age, a passion that his parents encouraged. At age sixteen, he discovered the beatnik subculture and was very much influenced by that literary movement. Though he studied at the University of Illinois and Chicago’s Roosevelt University before earning his B.A. in English from the University of Wisconsin, Spencer considers himself above all to be “an alumnus of the Chicago public library system.”

All of Spencer’s novels are intimately related to his life. He wrote his first novel,

Last Night at the Brain Thieves Ball

(1975), during and directly following his college years. The novel centers on a control-hungry experimental psychologist and his dangerous experiments, which reflected Spencer’s own experimentation with mind-altering drugs and his studies in behavioral psychology at the time. His second novel,

Preservation Hall

(1976), is about an ambitious man’s fateful encounter with his ex-convict step-brother while the two are snowed in together in an isolated rural house, not unlike the one Spencer would move to later in life in Rhinebeck, New York. His next novel,

Endless Love

, explores the obsessive and all-consuming relationship between a young couple and was his first major success, selling more than two million copies worldwide.

Endless Love

was universally hailed by critics, establishing Spencer as a leading American author, and inspiring the film directed by Franco Zeffirelli.

In 1986, Spencer published

Waking the Dead

, the story of the tragic love between a career politician and a progressive activist living in Chicago. The book was named a Notable Book of the Year by the

New York Times

and later became a film produced by Jodi Foster and starring Billy Crudup and Jennifer Connelly. Spencer followed the success of

Waking the Dead

with

Secret Anniversaries

(1990), a coming-of-age story of a young woman in mid-twentieth-century Washington, D.C., and

Men in Black

(1995), a comedic novel about a struggling author’s unexpected success after penning a book about UFOs.

Secret Anniversaries

and

Men in Black

is set partly in the fictional town of Leyden, New York, a town that Spencer revisits in many of his novels. Leyden and many of its residents are modeled after Rhinebeck, and Spencer says that, though he doesn’t directly base his characters on real people, he does draw from them and join different people’s traits together, “giving a red head a limp, a lawyer a dog.”

After

Men in Black

, Spencer published

The Rich Man’s Table

(1998), about the strained relationship between a Bob Dylan—like American music icon and his unacknowledged son. Most recently, Spencer has published the novels

A Ship Made of Paper

(2003),

Willing

(2008), and

Man in the Woods

(2010). Spencer’s nonfiction journalism has appeared in the

New York Times

,

The New Yorker

,

Rolling Stone

, and

GQ

. He has also taught fiction writing at Columbia University and at the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

This photo, taken around 1945, features four of the people who most influenced Spencer’s life. His father, Charles, is seen in his military uniform (second from the right), with Spencer’s aunt Elfride and uncle Harold to Charles’s right and his mother, Jean, to Charles’s left. Elfride and Harold both moved to Cuba after the 1960 Cuban Revolution.

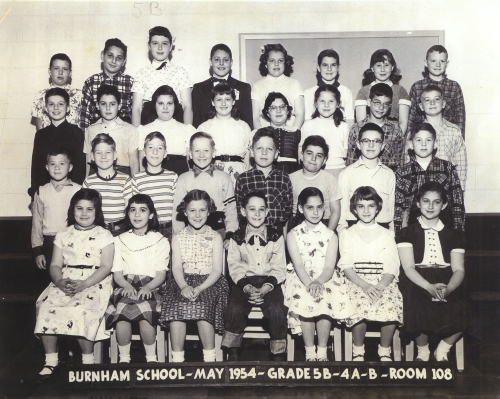

Spencer’s fourth grade class at Burnham Elementary School on Chicago’s South Side. Spencer is in the second row, fifth from the left.