Waiting for Snow in Havana (47 page)

Read Waiting for Snow in Havana Online

Authors: Carlos Eire

It's that glass table I want you to see in your mind. Kidney shaped, just like the shark pool. Thick, but not thick enough. Only half as thick as the fishbowl.

That table and this book have come out of hiding at the same time. This book was waiting to emerge for years and years, too, but it didn't until now.

You ask: why now? I say: I have as many reasons as the number of Cuba clouds I've seen in the past thirty-eight years, and none of them matter to you, really. If I told you anyway, all you'd see is a deep, dark abyss in which there are no parrot fish.

So let's get to the end.

Tony and I boarded the airplane at sunset, looking over our shoulders. We could see our family off in the distance, through the glass. Not darkly, but clearly, even in twilight. The last thing I saw before I died that day was my mother waving her cane and my father standing next to her, with his hands in his pockets. Those huge pockets in those ridiculously baggy pants, which he always pulled on over his shoes.

I plunged into the airplane and a whole new void. Tony plunged in too, his beautiful abyss in tow. Airport guy couldn't find it during the strip search, just as he couldn't find my forty-one lizards.

Want to know what it's like to die?

The kind of death I'm talking about has no oceans of time in which your memories swim eternally. No. This kind of death comes in a flash, as quick as lightning. And as silently as a lizard when it's squashed by a little boy with a broom. I heard the engines roaring, yes. I did. Who wouldn't, except a deaf person? I heard the engines clearly, so the silence I'm talking about is of a different kind.

It's the silence we find wrapped neatly inside every paradox.

The silence we can't approach without bowing.

The silence that humbles everyone, even the strongest and most fearsome.

Fidel will reach that silence, too, someday. Maybe soon. Maybe not.

It makes no difference when, really. Reach it he will.

It's the silence beyond words.

The silence beyond reason.

The unutterable unknown.

The all-knowing silence that only the third eye can see.

The joyous silence that accepts imperfection as the absolute perfection.

The burning silence, the sweet flame that knocks off your shoes and makes you cry out: “Fire! Fire! Fire! I'm vanishing, wholly consumed!”

Todo me voy consumiendo.

In the wink of an eyeâin a fraction of that, reallyâyou pass through the burning silence, and you emerge in exactly the same spot, in the very same body, gloriously transformed, a glowing blank slate.

It might not seem glorious at first, the transfiguration. But glorious it is, and glowing, and as blistering white as the whitest of clouds.

And as painful as all hell.

I had never flown in an airplane before. This was so exciting. The plane sped down the runway at what seemed an unearthly speed, the force pushing me back into my seat. We gained even more speed and suddenly we were aloft.

We were up in the air, no longer on Cuban soil. Aloft, like Peter Pan. Up among the clouds. And I saw the Cuban countryside below me for the first and the last time. Having been stuck inside beautiful, awful Havana all my life, I'd never really seen most of the lizard island. Louis XVI didn't like to travel, and he never took us very far beyond Havana. He had already seen most of the world in all his lifetimes, I guess.

I stared out the window, transfixed, as Cuba became smaller and smaller beneath us.

Look at all that green! Look at that! It's so, so green!

Imagine how many more lizards there must be down there!

Imagine all those voodoo people and demons left behind, there, right there, hidden in the midst of all that greenery!

Look at that! How funny! Look at those royal palms all over the place! They look just like those little cocktail toothpicks with the colored foil tops that held together those triangular ham salad sandwiches! Like the toothpicks in the sandwiches I ate after my First Communion!

Look at those clouds! They're so much puffier than they seem from the ground!

Look at that sea! It's bigger than I thought, so much bigger! And the waves, where are they? I can't see them. I wonder how many parrot fish are down there right now, and sharks. How many?

And will you look at that! That sun, setting over there!

It's tangerine, again, as always, and glowing like an incandescent host, but it's not setting where I've always seen it set. It's all sea, nothing but sea below us. There is no more Havana. No more tangerine Havana.

“It'll be so, so nice to be able to drink Coca-Cola again, won't it,” I said to Tony.

“Yeah, sure, and the chewing gum will be nice, too.”

“I'm going to ask for a Coke the minute I step off the plane.”

“And I'm going to ask for a whole pack of Doublemint gum.”

We had passed through the burning silence. Right through it. And here I am now, writing this. It's over, this part of it. But it's only a small part of the story. The silence can be beautiful. Don't let it ever scare you too much. Don't fear the abyss either.

Dying can be beautiful.

And waking up is even more beautiful. Even when the world has changed. Especially when the world has changed.

Tú sabes.

You know.

Imagine a tangerine sunrise that never ends, forever hovering over a swirling cloud of parrot fish in the turquoise sea.

Imagine killer waves coming at you, turquoise waves, under white white Cuba clouds that soak up the tangerine and make it even brighter.

Imagine no end of waves.

None.

No end.

Sin fin

.

En fin, sin fin

.

Tú sabes.

T

his book has been the greatest surprise of my life. I started writing it exactly two years ago, on the last day of Spring term 2000, with no plan or outline, or any idea of how long it would take to finish. Little did I know what lay in store.

Once I began, I couldn't stop. For the next four months I wrote every single night, from about 10 p.m. to 2 or 3 a.m., while teaching, chairing a department, mowing the lawn, swimming with the kids, and doing other research and writing. The only day I didn't work on this book that summer was the day I went in for surgery.

I honestly thought that by working so late at night I was only stealing time from myself. How wrong I was. My wife, Jane, tells me I vanished for four months. And she is right, of course; though I remained here I

was

gone. Off to another dimension, the world of this book. After years of studying the subject of bilocationâthe ability to be in two places simultaneouslyâI had managed to achieve it.

But bilocation exacts a great price. The self who remains at home can't perceive how little of him is actually there, how bilocation dilutes a person, and what an impact that has on his loved ones. Yet, despite my fragmentary existence, Jane encouraged me to keep writing and never look back over the night's work. She also kept telling me to trust in images and to forget everything I had ever written before. I did that too, somehow.

Saying “thank you, Jane” won't ever do. Jane, you were here while I was gone, encouraging me at every turn and pointing me in the right direction. You were here waiting for me, ready to embrace the unknown when I emerged from the silence at the end of the book, a changed man.

Gratitude

is such an insufficient word in this case, even a lame barbaric concept. Someother language would have to be invented to convey my thoughts and feelings adequately, some whole new way of thinking and speaking. I hope I can find it, learn it, and put it to good use, for if anyone ever deserved poems in a new superior tongue, and love undiluted, it would be you, Jane.

And the same goes for our children. Every night for four months they listened to me as I read them the previous night's work, and then they watched me fade away, only to reappear whole the following night with newly written pages in hand. No one could ask for a better audience than the three of you, or a more honest one. You kept me from faltering or choosing the wrong path. You also gave me the passport I needed for bilocation, and the visa too. For this and an infinite number of reasons, all of which I hope you will discover on your own, I dedicate the book to you, John-Carlos, Grace, and Bruno.

Needless to say, I am wholly indebted to those who appear in this book, both living and dead, the good and the bad and the indifferent. They

are

the book. My memories may not match theirs exactly, but I hope that they take no offense at seeing their own past as I have captured it. I would especially like to thank my mother, Maria Azucena, and my brother, Tony. You two made the past come alive for me so often, sometimes simply by choosing one word over another as you shared your memories with me, and your affection.

Gracias por todo

. I would also like to thank my agent, Alice Martell, for all her efforts on my behalf, for her counsel and her friendship. I'm convinced you're not just an angel, Alice, but one of the highest rank, the epitome of wisdom, energy, efficiency, humor, and compassion. Without you I would not have ended up with so many contracts so quickly, or so many translations, nor would I have known what to do when things looked bleak.

Without you I wouldn't have found Rachel Klayman, my editor at The Free Press, who has taught me more about writing than anyone ever has, and whose unerring insight and judgment have made this a much, much better book. Thank you, Rachel, for guiding me so expertly, and for helping me ferret out Kant from his hiding places in my prose. Thanks also for persisting, and for always having my best interests in mind, especially when I was blind to the truth.

I'm also certain that this book wouldn't have been written if it hadn't been for the fact that after decades of isolation from my own people and culture, I was lucky enough to end up working side by side with three extraordinary Cubans. Each awakened me from my slumbers in a different way, but all brought to life within me the same three things: an awareness of the past, an ache for a future forever lost, and a hope for a future yet unrevealed.

Georgina Dopico-Black, what can I say? I owe you far too much. You know what you have contributed and how indebted I am and always will be. Yet I still need to thank you here, no matter what, even if it seems a quixotic gesture, as ridiculous as time itself.

Danke schön

.

I also owe a lot to you, Maria Rosa Menocal. I hope you know how much I treasure our friendship.

Merci,

Maria Rosa, not just for steering me to Alice Martell, but for everything else down to our five-minute chat yesterday.

Roberto González EchevarrÃa, you've helped me more than you could imagine, my friend.

Gracias,

Roberto, for clueing me in to so many things, and for showing me the way to what is genuinely Cuban with every word and gesture.

My dear friends John Corrigan and Sheila Curran, you've also helped in ways unseen, perhaps without knowing it. Now you'll know it for sure, I hope. Thanks, as ever.

Finally, I would like to thank Father Robert Pelton of Madonna House and Father Carleton Jones of the Order of Preachers for helping me face the lizards and the dark night, and for simply being who they are, true ministers of boundless grace and light.

Dominus vobiscum

.

Guilford, Connecticut

May 2002

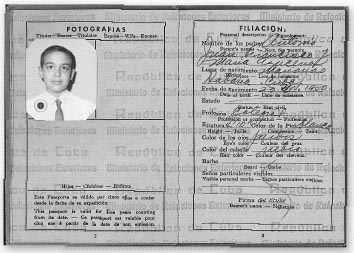

B

ORN IN

H

AVANA

in 1950, Carlos Eire left his homeland in 1962, one of fourteen thousand unaccompanied children airlifted out of Cuba by Operation Pedro Pan. After living in a series of foster homes in Florida and Illinois, he was reunited with his mother in Chicago in 1965. His father, who died in 1976, never left Cuba. After earning his Ph. D. at Yale University in 1979, Carlos Eire taught at St. John's University in Minnesota for two years and at the University of Virginia for fifteen. He is now the T. Lawrason Riggs Professor of History and Religious Studies at Yale University. He lives in Guilford, Connecticut, with his wife, Jane, and their three children. This is his first book without footnotes.