Wag the Dog (27 page)

Authors: Larry Beinhart

Tags: #Fiction, #Political, #Humorous, #Baker; James Addison - Fiction, #Atwater; Lee - Fiction, #Political Fiction, #Presidents, #Alternative History, #Westerns, #Alternative Histories (Fiction), #Political Satire, #Presidents - Election - Fiction, #Bush; George - Fiction, #Media Tie-In, #Election

A flagpole against the sky. A pair of hands enter the frame. They take down the Spanish flag. They hoist Old Glory.

That was it in its entirety, shot in 1898 when America declared war on Spain.

51

It was the first commercial war movie.

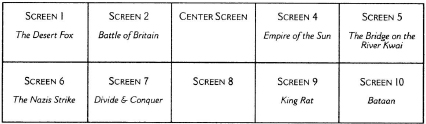

Then, on Screen 1, up in the left-hand corner, appeared Leni Riefenstahl's famous 1934 documentary,

Triumph of the Will.

Hundreds of thousands of uniformed members of the Master Race march, turn, salute, stand, sing,

heil!

Hitler rants. It is the declaration of the German people that they have turned themselves into the machine that will rule the world. They will annex, terrorize, invade, conquer, exterminate, incinerateâand this is the self-image in which they will do it. One people, One will. This is the image that they will sell to the world and the world will believe in even long after Hitler is dead and the war is lost.

52

On Screen 5, upper right-hand corner, the other beginning:

December 7th.

Quiet, peaceful Hawaii. Formations of Japanese planes appear, buzzing through the silent skies.

The sneak attack. The Japanese catch American boats sitting at anchor in the harbor at Honolulu. Battleship Row, pride of the American fleet, turns into the stinking black smoke of ruin. The American planes are all on the ground. Lined up, neat and orderly. Perfect targets. Helpless and defenseless, they are destroyed. Torpedoes. Ships on fire. Planes explode. Flames. Sailors running. Two sailors with a machine gun fight back, firing at the sky. One falls. The other keeps firing.

Backstage, as it were, on the other side of the video screens, a room of industrial shelving, steel racks, bundled cable, a spaghetti land of wiring, an unmasked array of monitors and machines, Teddy Brody was watching too. When Beagle wanted a film that had not yet been loaded into the Fujitsu and digitalized, Teddy was the librarian who roamed through the racks to find it on film, tape, or disc, and put it on a projector, VCR, or player.

He loved the sequence that Beagle had assembled. The implications were so intellectually evocative that Teddy was able to forget his terrible frustrationsâstuck here as librarian, not getting anywhere in his desire to be a director, not rising to a station where he could turn back to his parents and say, “Hey, you bastards, look at me, I'm making it, I don't need you to love me anymore and I never, ever will.” What he loved most was that the base of the pyramid, the foundation, the three cornerstones, were each of them a very special fraud.

Tearing Down the Spanish Flag

was not shot in Manila or Havana. It was shot on a rooftop in downtown Manhattan.

53

It was a terrific commercial success. The producers, Blackton and Smith, followed it up with the more elaborate

Battle of Santiago Bay,

the triumph of the American fleet over the Spanish in Cuba. That one was shot in a bathtub. The battleships were cutouts and the smoke of the naval guns came from a cigarette puffed across the camera lens by Mrs. Blackton.

The gargantuan rally that

Triumph of the Will

showed to the world really took place. However, the rally was staged for the camera.

54

This may not sound particularly striking today, when all lifeâpersonal life, sporting life, political lifeâis rerouted around prime time. But in the thirties reality was still presumed to be real and photographs didn't lie and no one had ever staged an event involving hundreds of thousands of people just so the camera could record them.

December 7th

won an Oscar as best short documentary.

55

The images that it established became the reference for future films. Footage was lifted and showed up in other documentaries. When feature films were made that included the attack on Pearl Harbor, filmmakers took great care to model their work on the record created by

December 7th.

But all the battle footage in

December 7th

was fake. The stricken ships were miniatures. They caught fire and billowed smoke in a tank, a larger, more sophisticated version of the bathtub in

The Battle of Santiago Bay.

The sailors running through the smoke and firing back at the Japs were running across a soundstage. The smoke was from a smoke machine. The tank and the stage were in Hollywood, California, a place that has never been bombed, torpedoed, or strafed.

Teddy Brody loved it. He loved Leni Riefenstahl, John

Ford, Blackton and Smith, and Mrs. Blackton too. He loved them for their audacity. There wasn't enough reality around, so they made some up. Teddy had spent a lot of time in academic circlesâB. A. from Yale Drama School, M. F. A. from UCLAâwhere facts were checked, where people were failed for inaccuracy and booted out for plagiarism, so he felt very tied to specific and literal truths and didn't know how to escape them. Besides, his father had been such a liarâso adamant and violent about denying itâthat it became very important to Teddy to keep precise score of who said exactly what, when they said it, when they changed it, and how they lied about it.

Center Screen went blank. Cut to black.

Victory in the West

came up alongside

Triumph of the Will.

Hitler's armies smashed through Belgium and Holland into France on Screen 2.

Hitler believed in the power of films. He destroyed entire cities for the purpose of creating images.

56

When the

Wehrmacht

went forth to conquer the world, every platoon had a cameraman, every regiment had its own PK,

Propaganda Kompanie.

57

Hitler conquered continental Europe very quickly and with very little resistance. Part of the reason was that he convinced his enemies that the

Thousand-Year Reich

was invincible. He fought with the power of the mind. By the time the French troops faced the Nazis, they had seen the massed rallies at Nuremberg, they'd seen the result of blitzkrieg in Poland. They'd seen it on the same screen on which they'd seen Charlie Chaplin and Maurice Chevalier and newsreels that brought them the results of bicycle races.

58

One by one, Beagle filled the screens with images of the enemy triumphant.

On the left the Nazis marched into Paris, conquered Yugoslavia and Greece, North Africa, and Ukraine, and the Baltic states. The Gestapo rounded up suspects and carted away Jews. They bombed innocent civilians in London.

Wake Island,

the fall of Singapore and of the Philippines came up on Screens 4, 5, 9, and 10 as Japan marched forward (cowardly) and the Americans fell back (heroically). John Wayne watched the Bataan death march. The victors put the vanquished in brutal prison camps to languish and die.

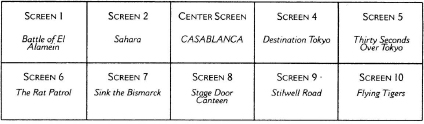

Casablanca

59

came up on the Center Screen. To Beagle there was something defining about it. In the rhythm of the history he was creating, weaving, imagizing, it deserved to come out of the dark and be center-screen. It was the moment of choiceâthat's what it wasâwhen we went from selfish absorption to commitment. Everyone had come to Rick's Café Americain; the refugeesâCzech, German, Jewish, Rumanian, and moreâLoyal French, Vichy French, a Russian, and the Nazis. And everyone's fate was dependent on what Rick decided to do.

Once Rick decided, all the images changed.

became

By the end of

Sahara,

Bogart and his six guys, including Frenchie, a Brit, and a black Sudanese, had captured an entire company of previously invincible Nazis.

Over on the right the United States began to strike back in the Pacific.

After that, America was on a roll. There was no stopping it. It was half-real, half-myth, and the two were mixed shamelessly. The military gave Hollywood footage, advisors,

equipment, soldiers, transport, cooperation. In return, the filmmakers gladly told the story that Washington and its soldiers wanted told, the way they wanted it told.

Center Screenâ

The Battle of San Pietro.

The opening statement on the screen: “All the scenes in this picture were shot within range of enemy small arms or artillery fire.” Oddly enough, this was true. While all around the Center Screen men ran, leapt, dashed, charged into battle, the American soldiers fighting their way up the spine of Italy

walked

into battle.

Beagle wondered if the film affected him so because it was where his father had fought. Maybe not at San Pietro, but in Italy. Where he had been wounded. Every time he watched the footage and saw the men being carried away or waiting on the stretchers, he looked to see his father's face. He never did, even with freeze-frames and digital enlargements. But he was sure that his father's face must have looked like the faces in the film. So extraordinarily ordinary. Unshaven. Cigarette smoking. Dying for a cup of joe. Wishing for just one fresh vegetable, a bite of onion, a bath. His father was dead. He couldn't ask him, “Dad, were you at San Pietro? Is that where you won your Purple Heart? Did you feel more for your country than I do? And can I somehow get there too? Was it better then? Was it as good as they make it seem in the movies?”

The men walked into the battle.

The film had been shot without sound. The director, Major John Huston, spoke the narration: “They were met by a wall of automatic-weapon and mortar fire. Volunteer patrols made desperate attempts to reach enemy lines and reduce strong points. Not a single member of any such patrol ever came back alive.”

Of all the hundreds of war films Beagle had watched, he considered this the best. It started with shots of barren fields and trees without fruit. It explained the battle, simply and clearly. It showed the fighting. It told what happened. “Sixteen tanks started down that road. Three reached the outskirts of the town. Of these, two were destroyed and one was missing.” It spoke of the casualties. “It was a very costly battle. After the battle the 143rd Infantry alone required eleven hundred replacements.” But the battle was finally won. The Germans

retreated. The Italians, villagers and peasant farmers, came out of the caves where they'd been hiding. Huston showed the faces of the children and the old women. He said: “The new-won earth at San Pietro was plowed and sown and it should yield a good harvest this year. And the people pray to their patron saint to intercede with God on behalf of those who came and delivered them and moved on to the north with the passing battle.”

He let all the screens go black so that he could hear this ending.

Bang! They all snapped back on again. The planes were flying over Germany and against the Japanese. Real ones like

Memphis Belle.

Fakes ones like

Memphis Belle,

the feature film that had been made fifty years later about the documentary.

Twelve O'Clock High. Victory Through Air Power

(Walt Disney's endorsement of bombing civilian targets),

Flying Leathernecks

(John Wayne).

Bombardier,

which showed that we need have no moral qualms about bombing citiesâthough that was one of the Nazis' crimesâbecause our bombing was precise. How precise? The crewman says: “Put one in the smokestack.” There are three of them down there. Bombardier: “Which one?” Crewman: “Center one.” Bombardier: “That's easy.”

The Center Screen's gone black again. But underneath it, Screen 8, Donald Duck sings,

“Heil, heil,

right in the Führer's face.” Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck fight the war. Bing Crosby sings for war bonds. Fred Astaire dances off to the Army. Gene Kelly dances off to war. Benny Goodman, Peggy Lee, Glenn Miller, Joe E. Brown, Bob Hope, and a lot of girls with breasts and legs whose names have been forgotten, Bette Midler in

For the Boys,

sing and dance and make that war, which was the good war, just a bit more of a fun war.