Vortex (27 page)

Authors: Robert Charles Wilson

“Okay, thank you,” Bose said. “Anything else Orrin talked about this morning that you can recall? Anything at all, even if it seems unimportant.”

“No. Just the weather, like I said. He was interested in the weather report coming over the radio in the coffee shop. They’re calling for heavy rain tonight. That excited him. ‘I guess it’s tonight,’ he said. ‘Tonight’s the night.’”

“Any idea what he meant by that?”

“Well, he always did like storms. You know. The thunder and all.”

* * *

Bose convinced Ariel to stay in her room, “otherwise I’ll end up looking for the both of you.” And Ariel had calmed down enough to see the sense in it.

“You’ll call me, though, right? Soon as you know anything?”

“I’ll call you whether we know anything or not.”

Back in the motel lobby, Bose talked to the desk clerk for a few minutes. Orrin had been waiting for the downtown bus, the clerk said. No, he hadn’t actually seen Orrin get on. Just noticed him waiting out there. Skinny guy in torn jeans and a yellow T-shirt standing in the sun by the side of the road. “Begging for heat stroke in this weather, if you ask me. Those buses only come along every forty-five minutes.”

“So what do we do?” Sandra asked when Bose had finished.

“Depends. Maybe you want to stay here with Ariel?”

“Or maybe I don’t.”

“I can think of a couple of places we might look.”

“You’re saying you know where he went?”

“I have an idea or two,” Bose said.

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

ALLISON’S STORY

Isaac Dvali explained how he’d turned off the Network surveillance. Turk sat warily still, watching Isaac, watching me.

“It’s true,” I said when Isaac finished, and I told him the rest of it: that I’d talked to Isaac days ago, that Isaac knew about our plan, and that (at least for the moment) the Network couldn’t hear a word we said.

I wasn’t sure he believed me until he stood up and came across the room and we looked at each other, our first honest look since we had begun planning our escape. Then we were in each other’s arms, trying to say all the things we wanted to say and managing only a happy-sad incoherency. But words didn’t matter. It was enough to be able to hold him without making a lie of it. Then my hand touched the node at the back of his neck: a patch of papery skin, a fleshy bump. He flinched, and we drew apart.

He turned to Isaac. “Thank you for doing this—”

“You’re welcome.”

“—but it’s a little confusing. I knew Isaac Dvali back in the Equatorian desert. You look like him, allowing for what happened, and I know they rebuilt you from Isaac’s body. But a lot of you must be pure Vox. And to be honest, you don’t sound much like the Isaac I knew.”

“I’m

not

the Isaac you knew. There isn’t a word for what I am.”

Turk was looking at him with Networked attention, reading the invisible signs. “What I’m saying is, I don’t understand why you’re here. I don’t know what you want.”

Isaac’s smile disappeared and a cold light came into his eyes, a light even I could see. “It doesn’t matter what I

want.

It never did! I didn’t ask to be injected with Hypothetical biotechnology when I was in my mother’s womb. I didn’t ask to be cycled through the temporal Arch, I didn’t ask to be brought back to life when I was decently dead. What I

wanted

was never germane. It isn’t now. My neural functions are shared with processors embedded in the Network. I’m chained to Vox, I can’t exist without it, and Vox is about to be consumed by something … incomprehensible.” He made a visible effort to control himself. “The Hypotheticals don’t care about anything as trivially brief as a human life. It’s the Coryphaeus that interests them. When the Hypothetical machines reach Vox, they’ll absorb the Coryphaeus and dismantle Vox Core. Nothing human will survive.”

I said, “How do you know that?”

“I can’t talk to the Hypotheticals—I’m not what Oscar thinks I am—but I can hear them ticking out in the dark. Not their thoughts—their

appetites.

” His face went slack and he closed his eyes—listening, maybe. Then he shook his head and looked at Turk. “You were there when I was in pain. Not because you thought I was a god. Not because you could use me. Not like the doctors, hovering over me like crows over carrion.”

“That’s little enough,” Turk said.

“If you can save yourselves, I want to help. That’s also

little enough.

”

“What about you?” I asked.

A trace of a smile returned to his face, but it was bitter. “If I can’t leave, I might be able to hide. I’ve been trying to create a protected space inside the Network. Not for my body but for my

self

. I mean to try. But the Hypotheticals are very powerful. And the Coryphaeus … the Coryphaeus is insane.”

* * *

The Coryphaeus is insane

.

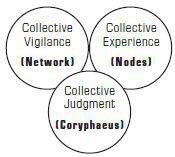

As Treya I hadn’t given the Coryphaeus much thought. Few of us did. The Coryphaeus was an abstraction, a name for the processors that quietly and invisibly mediated between Network and node. Our teachers had shown us a diagram to explain it:

—and that was as much as we had ever wanted or needed to know. The system was stable, self-protecting, self-perpetuating, and it had worked flawlessly for five centuries. What could it mean, then, to say that the Coryphaeus had gone mad?

The problem was the Voxish prophecies. Our founders had written them into the Coryphaeus as unalterable axioms—embedded truths, permanently exempt from debate or revision. That hadn’t mattered when the rapture of the Hypotheticals was a distant goal toward which we moved in gradual increments. But now we had come to the blunt end of the question. Prophecy had collided with reality, and the obvious inference—that the prophecies might have been mistaken—was a possibility the Coryphaeus was forbidden to consider.

That conflict was being played out in the surveillance and infrastructure systems that bound together our lives and our technology; it was being played out in the limbic interfaces and private emotions of everyone who wore a node. “What makes it especially dangerous,” Isaac said, “is that we can’t predict the result. The most likely outcome is an asymptotic trend toward self-destructive behavior in both the organic and inanimate aspects of the system.” He added, “It’s already happening … more quickly than I anticipated.”

I asked him what he meant, then wished I hadn’t.

“The end of Vox is days away. That means there’s no need for a surplus food supply. Or surplus people, if they’re not a willing part of the process.” He looked away, as if he couldn’t bear to meet our eyes. “The Coryphaeus is killing the last of the Farmers.”

* * *

I refused to believe it until I had seen evidence. As soon as Isaac left I rode vertical transit to one of the high towers and found a panoramic window. It was night, but the sky was unusually clear and the moon was bright on the northern horizon.

The Farmers had lived in the hollow spaces under the outlying islands of the Vox archipelago. They had numbered about thirty thousand souls before the rebellion—fewer, but at least half that many, after.

Now: none.

The out-islands were sinking. The Coryphaeus had cut them loose from the central island and opened their ancient accessways to the sea.

Any Farmers who survived the initial flooding, perhaps by climbing to the highest tiers of their enclosures, were dying as I watched. The Ross Sea drew the islands down in great upwellings of violet-colored froth. Geysers of water erupted from severed transit tunnels and ports. Cliffs of salt-encrusted granite heaved up dripping from the poisonous sea, then turned and settled beneath it forever, leaving oily residue and the tangled branches of dead forests.

I stood there for most of an hour, too shocked even to weep.

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

SANDRA AND BOSE

Bose took her past the place where Orrin had once rented a room. It was a five-story walk-up in a part of town you drove through with your doors locked: windows like eyes shut against the sullen indifference of the heat-stricken street, a doorway littered with broken syringes. Up in one of those rooms, Sandra thought, in the long afternoons before the night shift began, Orrin must have patiently filled his notebooks, page by page, day after day. “You think he came back here?”

“No,” Bose said. “But I don’t know how well Orrin knows the rest of the city. He has forty dollars in his pocket and I doubt he ever hailed a cab in his life. He’s taking transit and he might have decided to stick to the route he knows.”

“Route to where?”

“To the Findley warehouse,” Bose said.

* * *

So they followed the bus routes Orrin once would have taken to work, hot streets clotted with traffic under a sky dark with thunderheads. The afternoon light was fading by the time Bose turned off into a neighborhood of single-story industrial buildings set back in lifeless yellow lawns. The buildings housed small manufacturers and regional distributors, none of which seemed especially prosperous.

Bose parked in the lot of a corner gas station with a coffee-and-doughnut shop attached to it. Sandra said, “Are we close to the warehouse?”

“Close enough.”

Bose suggested coffee. The restaurant, if she could dignify it with that name, held a dozen small tables, all vacant. The windowsills were dusty and the green linoleum was peeling where the floor met the walls, but at least the place was air-conditioned. “Better get something to eat,” Bose said. “We might be here a while.” She ended up carrying a muffin and coffee to a corner table. From this angle she could see the street, the long row of anonymous buildings on the far side, the threatening sky. Was one of these buildings the Findley warehouse?

Bose shook his head: “The Findley warehouse is around the corner and a couple of long blocks down, but the nearest bus stop is just across the street—see it?”

A rusty transit sign bolted to a light standard, a concrete bench tagged with ancient graffiti. “Yes.”

“If Orrin comes by bus, that’s where he’ll get off.”

“So we’re just going to sit here and wait for him?”

“You’re going to sit here. I’m going to scout around the neighborhood in case he got here ahead of us, though I doubt that. I don’t really expect him until after dark.”

“You’re basing this on what, intuition?”

“Did you finish reading Orrin’s document?”

“Not all of it. Not yet.”

“You have it with you?”

“A printout. In my bag.”

“Why don’t you read the rest of it, and we’ll talk about it when I get back.”

* * *

She read it while Bose did his drive-around, and she was within a few pages of the end when he pulled back into the lot. He parked behind the restaurant’s Dumpster where the car would be hard to see from the street—an act of prudence or paranoia, she thought. “Find anything?” she asked when he came through the door.

“Nope.” He ordered another coffee and a sandwich and she heard him ask the woman behind the counter, “You mind if we sit here a while more?”

“Sit as long as you like,” she said. “We do most of our business at lunch. It’s mainly drive-through after three. Make yourselves comfortable. Long as you buy a little something now and then.”

“There’s a tip in it for you if you keep a fresh pot brewing.”

“We’re not allowed to accept tips for counter service.”

“I’ll never tell,” Bose said.

The woman smiled. “Looks like the rain’s starting. Good time to be indoors.”

Sandra saw the first fat drops strike the restaurant window. Moments later, water was washing down the glass in quavery sheets. Rain bounced from the steaming asphalt of the parking lot, and the scent of moist, tepid air seeped under the door.

Bose peeled a layer of plastic wrap off his sandwich. “You finished Orrin’s story?”

“Just about.”

“You understand why I think he’s headed here?”

She nodded tentatively. “Orrin—or whoever wrote this—obviously knows a few things about the Findley family. Whether they’re

true

or not is a different question.”