Voices from the Dark Years (43 page)

Read Voices from the Dark Years Online

Authors: Douglas Boyd

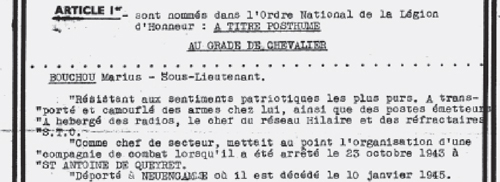

Marius Bouchou’s posthumous citation

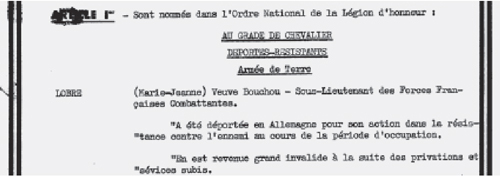

Marie-Jeanne Bouchou’s citation

At Camp Dora, Mignon toiled with Lucienne’s husband for months in underground factories building V-weapons, allowed out into daylight only to witness the hanging of fellow prisoners. On the death march westwards as the Red Army approached, 2,400 prisoners were locked inside a barn in a half-track park that was heavily bombed by Allied aircraft. Mignon and Beaupertuis were among 337 survivors next morning. Back in France, Lucienne could not recognise her husband in the hospital: the powerful peasant farmer who had weighed 102 kg when arrested was reduced to a skeletal 43kg. Cathérine Bouchou’s mother also returned from the camps prematurely aged and with broken health, unable even to smile for the ritual photograph at her daughter’s wedding.

None of the survivors spoke of their experiences, even to each other. There are many stories like that of Faytout’s group, on which the author stumbled when a cache of arms was found beneath a concrete wine press near his home in Gironde, where it had been hidden by one of the men who never came back. It comprised an assortment of Mark 2 Sten guns, Browning pistols and Lee-Enfield and French MAS 36 rifles, together with a large quantity of .303 ammunition for the Lee-Enfields and Brens, plus 9mm rounds for the Stens and Brownings. Most of the weapons were no longer in working order, due to rust, but the ammunition was in mint-condition in its original, waxed cardboard boxes.

On the other side of France, Klaus Barbie was targeting bigger game than Faytout’s little group. In November 1942 Jean Moulin had drawn the three main movements of the southern zone – Combat, Libération-Sud and FTP – into a loose federation titled Les Mouvements Unis de la Résistance (MUR). As the plurality of the title indicates, command was divided, with Captain Frenay refusing to subordinate his combat organisation to the FTP and both FTP and Libération claiming he was a militaristic dictator. The differences between the various leaders were complicated by the infiltration into the other movements of undercover communists nicknamed ‘submarines’.

Since none of the leaders agreed to work with the others, Moulin harnessed them loosely to his troika by doling out subsidies from funds parachuted with arms drops – and then withdrawing support when someone became difficult. In the first five months of 1943 his subsidies totalled 71

million

francs.

4

As to what was done with this money, researchers draw a blank, since most Resistance operations at this point cost no more than a few bullets.

Doriot declared in August 1944 that 600 of his men had been ‘treacherously gunned down by terrorists’. The first to die was Paul de Gassoski, killed by the Resistance on 24 April 1943. In his memoirs, Abetz stated that the first three quarters of 1943 saw 281 Germans, 79 French police and gendarmes, and 174

collabos

assassinated. Whatever the actual figures, the real price was paid by the hostages executed in reprisal: historian Robert Aron quoted the tally of the German chaplain at Fresnes prison: 1,500 to 1,700 men and women shot in Paris prisons alone during the occupation.

A neutral picture of Milice activities at the time comes from a report of 11 May 1943 by Prefect François Martin, informing Laval about an incident when

miliciens

stopped people in the street at gun-point and demanded their papers. Martin had the courage to state categorically that, had he been present at the time, he would have ordered the arrest of individuals arrogating to themselves police functions in this way.

5

Although Moulin’s brief from London ran only in the southern zone, like many other agents in the field, he also made unauthorised contacts – for example, with the PCF hard core in Paris, working directly for Moscow. Suspecting as much, Colonel Passy defied all the canons of intelligence work by parachuting into France at the end of February 1943. Instead of working with him, Moulin chose the moment to return to London and did not return to France until 21 March.

On 7 June in Paris the Gestapo arrested Moulin’s military counterpart General Charles Delestraint, code name Vidal, who understood German and was fully aware of his position. There could be no question of denying his mission or identity, since he had on him when arrested identity papers in his true name. Detained with him was

Résistant

René Hardy, who was liberated a few days later with no marks of ill treatment, but did not tell his comrades what had happened. On 27 May Moulin committed the worst mistake possible for a clandestine agent, who already knew he was being hunted all over France, by calling a meeting in Caluire, a suburb of Lyon, of

all

the Resistance bosses, any one of whom was likely to be under surveillance. It is hard to find a sane reason for such a major error.

The venue, in the house of a dental surgeon, was chosen because it was thought they could enter and leave unnoticed among his patients. Frenay, in London for a briefing, was represented by his No. 2, Henri Aubry, who brought along René Hardy, who is most likely to have told Klaus Barbie the time and place, plus the fact that Moulin would be present. The house was already staked out before they arrived, and the meeting had just begun when Barbie’s men burst in and handcuffed everyone, including genuine patients awaiting treatment. As they were being herded into closed vans, Hardy made a run for it. Despite several Gestapo men turning automatic weapons in his direction, he escaped with only a slight leg wound – a remarkable achievement with one’s wrists cuffed behind one’s back. Despite two post-war trials, his exact role in the betrayal was never resolved.

In the torture chambers Barbie used in the École de Santé Militaire, Moulin claimed he was Jacques Martel, an art dealer from Nice. To prove it, he gave the address of his genuine art gallery there. Barbie replied by calling him by his Resistance code name, Max. What happened in the following thirty hours is best left to the imagination. The local French police reported the arrest routinely, between reports of ID cards stolen from a Mairie and an increase in thefts of vegetables from gardens. On the evening of 23 June in Montluc prison the ‘trusty’ prison barber was called to shave an unconscious man, who had obviously been tortured nearly to death, and whose flesh was cold to his touch. Moulin mumbled something in English and then asked for water. The guard rinsed out a shaving mug and the barber held it to Moulin’s mouth, but he could only swallow a few drops before losing consciousness again.

Driven to Paris, he was briefly lodged in a cell at No. 40 Boulevard Victor Hugo, a suburban villa in Neuilly used by Bömelburg’s men as an interrogation centre. Prisoners André Lassagne and Delestraint were brought there from Fresnes prison to be shown Moulin lying on a stretcher. Noting that his skin had turned yellow and his respiration was hardly noticeable, Lassagne denied knowing him. The dignified Delestraint replied to the guards’ question with, ‘How do you expect me to identify a man in that condition?’ Officially, Jean Moulin died on a train taking him to Germany on 8 July 1943, aged 44. General Delestraint was transferred to the concentration camp at Natzwiller and from there, in September, to Dachau, where he was shot and cremated on the morning of 19 April 1945, aged 64. In one successful operation the SD had neutralised both the military and the political leaders of the Gaullist Resistance.

On 10 June 1943 SS-Hauptsturmführer Aloïs Brunner, fresh from annihilating the 35,000-strong Sephardi Jewish community in Salonika, arrived in Paris. Three weeks later, he replaced the corrupt and brutal gendarmes guarding Drancy with Feldgendarmerie soldiers, whose 21-year-old commander SS-Sturmführer Ernst Heinrichsohn had the body and grace of a ballet dancer. He took pleasure in attending the selections for transportation, slapping a riding crop against his boots. When short of victims for his next transport, Heinrichsohn drove to the Rothschild Hospital and had thirty-five patients aged between 70 and 90 dragged out of bed to make up the number. Of 536 adults and sixty-three children in that transport, only two survived to return to France.

Brunner also set up thirteen interrogation sub-stations in Paris, manned by members of the

carlingue

who had no qualms about torturing suspects. The most infamous was at 93 rue Lauriston, run by violent gangster Henri Lafont and renegade police inspector Pierre Bonny, a ‘real family man’ who never spoke at home about the work at which he spent long hours each day.

6

So useful was Lafont that he was given both German citizenship and SS officer rank.

Intensive ID checks at all main stations made it dangerous for the Moissac Rovers to travel far, so that the task of visiting children in foster homes fell more and more to the Rangers – who yet found time for love. In July 1943 a 22-year-old helper, code-named Sultane, married Pierre Kanthine, a teacher working with the

colonie.

It was a brief marriage: on a clandestine trip to Rouffignac in the Dordogne shortly afterwards, the bridegroom was denounced by the mayor and taken hostage. In reprisal for a Maquis attack in March 1944 he was shot on the last day of the month.

Seen from London, these tragedies were unimportant to the course of the war. Colonel Bevan’s Operation Cockade still aimed to keep the Germans believing an invasion was imminent, so corroboratory arms drops to the Resistance built up during 1943 on a scale that could not fail to alert the Abwehr and SD. Drops of high explosive totalled 88 tons in January alone and rose to a peak of 10,252 tons in June, when 10,790 pistols, 2,353 Stens and 5,537 grenades were dropped, among other materiel.

7

In western France during April–May, Suttil’s Prosper network received 1,006 Stens, 1,877 incendiary devices and 4,489 grenades; in June it took delivery of another 190 man-sized containers of materiel on thirty-three landing grounds spread over twelve

départements

. The south-western Scientist network received 121 consignments of arms between May and August. During August the BBC twice broadcast coded messages, alerting agents in Prosper and Scientist to an invasion scheduled for September, failing only to send the confirmation messages on the night before the spoof operation.

8

Bilingual, having grown up in England and France with an English father and French mother, Francis Suttill may have been a good lawyer, but lacked the paranoia vital for undercover work. He remained unaware that the Germans, thanks to a triple agent, were watching virtually all his movements. Flyer and con-man Henri Déricourt, listed in the SD archives as agent BOE/48, afterwards summed up Suttill as more suited to being an officer in a gung-ho cavalry regiment than clandestine warfare. It was Déricourt who co-ordinated the scores of drops to Prosper, feeding times and places and arrival and departure of agents to SS-Sturmbannführer Bömelburg in Paris.

9

What Bömelburg did not know was that his double agent was in fact a triple agent acting under instructions from Colonel Bevan that over-rode his duties for Section F. This was the real dirt of Operation Cockade.

By the second week of July both Suttill and his No. 2 Gilbert Norman were in Gestapo cells divulging the false invasion plans. Several hundred other Prosper agents were also arrested, tortured, deported or shot straight away. It seems likely that the rolling-up of Suttil’s network was due to appalling security, rather than planned by Colonel Bevan, who intended Cockade to run right up to the real D-Day. Bevan’s own security was so tight that Buckmaster was prepared to put in writing as late as December 1945 that Déricourt was innocent of any collaboration with the Germans, and ‘had the finest record of operations completed of any member of SOE’.

10

The suffering of thousands of French men and women ensnared in these machinations can never be calculated.