Voices from the Dark Years (35 page)

Read Voices from the Dark Years Online

Authors: Douglas Boyd

Author George Orwell broadcast over the BBC that day:

Laval is a French millionaire who has been known for many years to be a direct agent of the Nazi government. Since the armistice he has worked for what is called ‘collaboration’ between France and Germany, meaning that France should … take part in the war against Russia. There is a very great danger that at some critical moment Laval may succeed in throwing the French fleet into battle against the British Navy, which is already struggling against the combined navies of three nations.

12

This was pure propaganda. As Laval told his judges after the Liberation, he had zero authority over Darlan’s navy at any time. A letter he wrote to the US ambassador in Vichy, Admiral William Leahy, on 22 April explained his increasingly pro-German policies as opposition to the UK–USSR alliance: ‘In the event of a victory over Germany by Soviet Russia and England, Bolshevism in Europe would inevitably follow. I believe … that a German victory is preferable to a British and Soviet victory.’

13

However, his draft text of a broadcast implying that the Germans would win the war caused Pétain to snort derisively, ‘You are not a soldier, Mr Laval. So how can you know? You may say that you

hope

for a German victory. That is all.’

Laval not only said that on air, he also ordered the COs to direct companies to send teams of workmen under their own foremen to Germany, where they would acquire new skills and knowledge. This was another of his attempts to get back the POWs on a one-for-one basis, news having reached him that French and Belgian POWs who refused to work, had been caught escaping or were suspected of planning escapes, were transferred to a complex of camps around Rawa-Ruska on the Polish–Ukrainian border, where conditions were so appalling that men died like flies from malnutrition and overwork in the quarries, buried in mass graves with hundreds of thousands of Soviet POWs. Approximately 25,000 western European POWs were eventually killed off in this way. Laval’s initiative flopped when an approach by the CO of the leather processing industry was turned down by the Wehrmacht, in whose camps the POWs were detained.

A few POWs were still managing to make a home run. On 17 April General Henri Giraud escaped from the castle of Königstein near Dresden – a sort of Colditz for French officers – after thirteen months’ captivity. With his photograph in every Gestapo and SD office, he reported: ‘The Alsatians were ready not only to give a prisoner money, but to risk their lives for him. Without knowing a single person there or being helped by any organisation, I passed right through Alsace without problem.’

14

The province having been declared German by force, helping escapers was high treason, punishable only by death, as Lucienne Welschinger and four accomplices found out on 29 January 1943 at the High Court in Strasbourg. Their mostly female

réseau

had helped several hundred escaped POWs through Alsace and Lorraine on their way home. Their execution did not discourage Father Mansuy, a veteran who had lost an eye and an arm in the First World War. In August 1940 he had delivered a sermon on the text of the Good Samaritan to a congregation of restive POWs, ending with, ‘If you ever need a Good Samaritan, here is my address’. When he was arrested after sheltering 2,500 escapees, the Gestapo said finding him had been easy because his address was in every camp.

Reporting for duty in Vichy, Giraud was received by Pétain on 28 April 1942 and on 2 May accompanied Darlan and Laval to meet Abetz at Moulins. High on his success in getting Laval back into power, Abetz sought to grease the wheels of collaboration by suggesting Giraud join the French delegation in Berlin, but the general refused, stipulating that he would return to Germany after 400,000 married POWs were released to rejoin their wives and families.

One of Laval’s first appointments made the young and brilliant prefect of the Marne

département

Secretary-General of the Police Nationale. René Bousquet had been decorated with the Légion d’Honneur at the age of 21 for saving lives during severe floods, and had also won a Croix de Guerre during the Battle of France in 1940. He left the Marne with a reputation of being anti-Masonic and anti-communist, but with no taint of anti-Semitism. Indeed, he claimed later to have organised food parcels for the detainees in the German concentration camp at Compiégne.

Himmler’s deputy Reinhardt Heydrich visited Paris, not to see the sights but to impose a tighter collaboration with the French police and gendarmerie, demanding that they all be placed under Oberg’s orders – for which a precedent existed in Belgium. He also introduced to France the Teutonic concept of

Sippenhaft

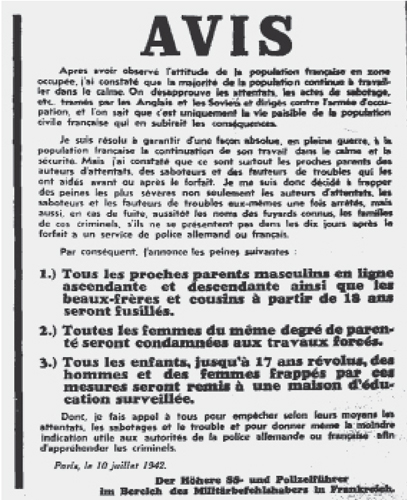

, or kin liability, under which the members of a terrorist’s family would be punished for his acts.

Under this ordinance, all the male parents, grandparents and children aged 18 upwards of arrested ‘terrorists’ were to be shot and all female parents, grandparents and children condemned to forced labour; children under 18 were to be sent to an approved school. At a conference in the Ritz Hotel with Heydrich and Oberg, Bousquet agreed to speed up the arrest and deportation of Jews. On 5 May, journalist Louis Darquier de Pellepoix replaced Vallat as head of the Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives (CGQJ). Darquier’s wife was British, and he had added the aristocratic ‘de Pellepoix’ to his name for reasons of vanity. Despite an excellent service record, in 1939 he had been given a three-month sentence for inciting racial hatred. He was the ideal man for the job, Vallat having been judged too squeamish.

A poster proclaiming the Sippenhaft ordinance.

Cardinal Baudrillart having departed this life, on 26 May 1942 the diplomat and author Paul Claudel addressed to Cardinal Gerlier a letter:

Your Eminence,

I have read with great interest the account of the splendid official and religious funeral ceremonies for His Eminence Cardinal Baudrillart. A wreath offered by the occupation authorities was apparently to be seen on the coffin. Such homage was clearly the due of so fervent a collaborator.

On the same day I heard the report of the execution of twenty-seven hostages in Nantes. Having been loaded onto trucks by collaborators, these Frenchman started to sing

La Marseillaise

. From the other side of the barbed wire, their comrades joined in. They were shot in groups of nine in a sandy hollow. Gaston Mouquet, a youth of seventeen, fainted but was shot anyway.

When the cardinal reaches the other side, the twenty-seven dead hostages at the head of an army that grows daily larger, will slope arms and act as his guard of honour. For Baudrillart, the French Church could not find too much incense. For those sacrificed Frenchmen, there was not a prayer, nor a single gesture of charity or indignation.

15

From 29 May 1942 Jews in the Occupied Zone aged 6 and over were obliged to wear, firmly stitched onto the left breast of their outer clothing, a yellow star the size of a man’s hand that had to be purchased with their precious clothing coupons: three stars cost one ticket.

Dérogations

or certificates permitting holders not to wear a star were hard to come by from the CGQJ, even by bribery or personal connections. When leaving her country home, the wife of Fernand de Brinon was careful to carry everywhere with her a pass bearing this magic formula: ‘The Commandant of the SIPO and the SD hereby certifies that Madame de Brinon, née Jeanne-Louise Franck, born on 23 April 1896, is excused from wearing the Jewish star, until final clarification of her origins.’

16

She was in rather limited company. Pétain personally intervened on behalf of three friends; eight fixers working for the German procurement offices were exempted; the Gestapo and anti-Jewish police gave out thirteen other certificates to people working for them. Strangely, Jews with British or neutral nationality were not required to wear stars. The rich and famous could ask a friend like Sacha Guitry for help and he would call on Abetz or some other high functionary to help, among them Colette’s husband, Clemenceau’s son Michel and the wife of Gen Alphonse Juin, the Commander-in-Chief of French forces in North Africa. Cafés, restaurants, cinemas and museums were out of bounds to Jews in case they contaminated subsequent gentile visitors – as were telephone kiosks and lifts. The same ‘logic’ confined them to the last carriage of Metro trains.

In the south-west, the yellow star ordinance was followed by the appointment on 5 June of Maurice Papon, an ambitious graduate of the high-powered École de Sciences Politiques, to the post of secretary-general in the prefecture at Bordeaux, where he would sign deportation orders for 1,690 adults and children, many of them French citizens. Although her children were not technically Jewish under the German ordinance, Renée de Monbrison wanted them safe from the likes of Papon, who now had thousands of Jews behind wire in twenty concentration camps all over France.

A map of concentration and deportation camps, August 1942.

To lessen the anguish of families divided by the Demarcation Line, the government had arranged with the German authorities for schools in the Occupied Zone to issue travel permits for children to visit relatives in the Free Zone during the long summer holidays. Renée obtained

laissez-passer

s for hers to go to their great-uncle’s château of St-Roch, near Moissac, where their demobilised father Hubert was based, when not living a clandestine life as ‘Monsieur Casaubon’, collecting military information about the German dispositions in the area between Bordeaux and Irun for onward transmission to London.

Unable to accompany them, Renée swallowed her anxiety and said goodbye to 14-year-old Françoise, 11-year-old Christian, 7-year-old Manon and 6-year-old Jean, knowing that they would never return to the Occupied Zone. Living alone in the villa at Le Pyla, she had to wear a yellow star each time she ventured outside. With that and

JUIVE

stamped in red letters on her identity card, no Germans offered her a seat on a bus; now she was obliged to give her seat up to them. More importantly, there was no way she could cross the line legally to be with the children.

There was another relative for whom Renée felt responsible. The identity papers of her aged Aunt Loulou Warshavski would shortly be a one-way ticket to the gas chambers. A few weeks after the children’s departure, she therefore took the old lady ‘on holiday’ to Hagetmau, a village lost in the largest forest in Europe, La Forêt des Landes. Arriving with one small suitcase each, they went to the house of a

passeur

who worked for money. A local child was bribed with sweets to hold the old lady’s hand, as though taking a walk with her grandma. The child was paid off with more sweets at the end of the village street, and they continued in pouring rain towards the line, the aunt under her umbrella with the

passeur

carrying her suitcase and Rénée with a young officer on leave, who had volunteered to walk with her arm in arm as though lovers out for a stroll, despite a torrential downpour which they hoped would keep curious people indoors.

The noise of a motorbike rapidly approaching from behind caused them a bad moment, but the Wehrmacht despatch rider did not stop, perhaps because of the rain. On paper, it was as easy as that, but one can imagine the heart-stopping anguish as the motorcyclist approached, or the sound of a voice or the barking of some farm dog seemed to presage a patrol of armed men and dogs.