Voices from the Dark Years (28 page)

Read Voices from the Dark Years Online

Authors: Douglas Boyd

On 2 June 1941 Pétain issued a second Statut des Juifs, obliging heads of Jewish families in both zones to register with the local town hall, which records later proved invaluable to the Milice and the SS in scooping up victims. The list of professional activities barred to Jews was now so long that it effectively left them unable to earn a living. The only statutory exceptions were for those who had rendered exceptional service to the French state (an ambiguous term by then) or whose family had been in France for at least five generations and rendered exceptional service to the French state during this time. Other restrictions were reflected in letters all account holders received from their bank managers in the week of 13 June, requiring them to send an attestation of racial purity. Failure to do so for any reason resulted in seizure of the account.

The doyen of the Paris bar, Maître Pierre Masse, replied to Pétain on learning that Jewish citizens might no longer be officers in the armed services:

I should be obliged if you would tell me how I withdraw rank from my brother, a lieutenant in 36th Infantry Regiment, killed at Douaumont in April 1916; from my son-in-law, second-lieutenant in the Dragoons, killed in Belgium in May 1940; from my nephew, J.F. Masse, lieutenant in 23rd Colonial Regiment, killed at Rethel in May 1940. May I leave with my brother his Médaille Militaire, with which he was buried? May my son Jacques, second-lieutenant in the Chasseurs Alpins, wounded at Soupir in June 1940, keep his rank? Can I also be assured that no one will retrospectively take back the Saint Helena medal from my great-grandfather?

6

Courage availing nothing, Masse was transported in 1941 and later died in Germany.

These and other heart-rending appeals for protection by the state they had well served were forwarded from Vichy to Pétain’s avidly pro-German official delegate in Paris, Fernand de Brinon. How many letters were actually seen by the marshal is an unresolved question. The probable answer is not very many, since Ménétrel personally sorted all mail to ensure nothing untoward arrived on his master’s desk. A later letter that was acknowledged came from Victor Faynzylber, who also sent a photograph of himself wearing both the Croix de Guerre and Médaille Militaire and standing with the help of the crutches he needed since losing a leg in the 1940 defeat. With him in the picture are his two children, the daughter of seven bearing her yellow star in conformity with the German ordinance. The plea was not for the veteran himself, but for the release of his wife, held at Drancy. It went unheeded, both she and later her husband being killed after transportation to Germany.

7

On 11 August 1941 a group of eighteen veterans wearing a total of seventy medals came to Vichy to request that anti-Semitic propaganda be dropped in official army publications, but no one listened. Not even when Pétain himself had signed the citation did a medal protect – as in the case of André Gerschel, dismissed as mayor of Calais.

8

Retired General Staff Officer Jacques Helbronner had personally lobbied for Pétain’s advancement in the First World War, but his appeal to the marshal did not save him or his family, transported and gassed at Auschwitz in 1943.

For some tastes, the anti-Semitic laws were far too lenient.

Le Petit Parisien

commented:

The Jews wanted this war and have thrown the world into a hideous conflict, in the light of which crime the present measures seem benign. It seems impossible that these people, running 80 per cent of the black market should spend their money so shamefully earned while the great majority of the French people have a very hard life of it at the moment.

9

The reference to the black market was echoed in a contemporary poster that showed two caricature Jews swapping a loaf for cash.

In Paris, Hauptsturmführer Danneker’s fan mail after the second ordinance included a letter from ‘The Group of Anti-Semitic Friends’ asking him to do something to stop Jews riding in cyclo-taxis pedalled by Aryans, having their baggage carried by Aryan porters or their shoes shined by Aryans. Whatever one’s race, with new shoes meaning wooden soles, rather fittingly the annual Grenoble Fair was declared the ‘first fair of the Ersatz’, introducing among other delights street signs that were no longer made in enamelled metal but Bakelite, first of the plastics family.

At the beginning of June, eleven young women and nine young men from various walks of life were shipped off to Drancy for mocking the yellow star ordinance by wearing either stars marked ‘Jew’ or ‘French’ or similarly shaped yellow objects on their clothing. Hailed as heroes by the other detainees, they were held in the camp for three months to give them a taste of what it actually meant to

be

Jewish. On 21 June, convinced that his captors intended to kill him eventually, Pierre Mendès-France escaped from Clermont-Ferrand prison. Refusing to go with him for fear of reprisals against his family, cell-mate Jean Zay was murdered by the Milice in June 1944.

News of the escape was overshadowed by events of greater import. On 21 June a handful of Germans in the know suggested with a wink to French friends that they should listen to the radio next day, when the hot news was the launch of Operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s invasion of the USSR. On 30 June 1941 Pétain severed relations with the USSR, but most French people were far more worried by the introduction of clothes rationing the next day, with a national appeal for them to hand in unwanted or outgrown garments, in return for which they would be given extra clothing coupons. This fell on deaf ears, anyone with surplus clothes preferring to trade them for a few eggs or a loaf of bread.

That summer’s Paris fair boasted footwear of wood, straw and synthetic leather, fashion designers backing the skirt-culotte as the smart garment for chic Parisiennes to wear on their bicycles, with the advantage that they could bend down to pump up their tyres and cycle home without fear of an importunate breeze revealing intimate secrets to male eyes. And cycles there were, everywhere. By the end of the occupation, 2 million were registered in Greater Paris, where new ones cost the price of a car before the war.

On 13 July de Gaulle asked every patriot over the radio to go out the next day sporting the national colours of red, white and blue. In the seaside town of Arcachon, Rénée de Monbrison did so, her children similarly dressed. A less courageous stranger sidled up to her, whispering,

‘Salut, bonne Française.’

In Paris a handful of men wearing tricolour handkerchiefs poking out of their breast pockets were arrested. More prudent folk preferred not to show in public they were listening to the BBC. Just how many did is illustrated by a current joke:

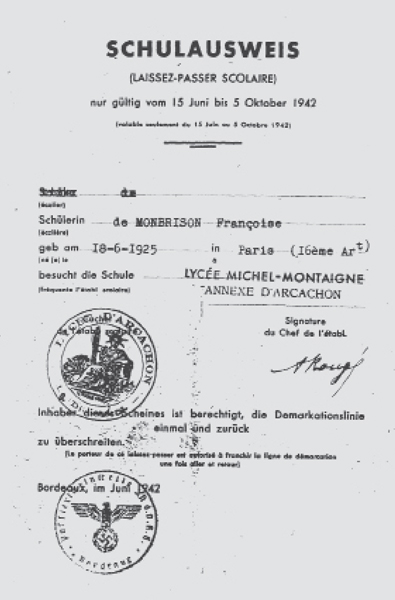

Françoise de Brison’s pass to cross the line.

Question: What would you say if I told you a Jew killed a German in the street at 9.30 pm and ate his brain? Answer: First, a German has no brain. Second, Jews don’t eat pork. And third, no one’s in the street at 9.30. Everyone’s listening to the news on BBC.

The Church disapproved, with Cardinal Liénart of Lille saying, ‘Do not listen to London or [the German station in] Paris. Listen to Lyon and Toulouse’,

10

in other words, the voice of the Church hierarchy.German propaganda attempted to discredit the BBC with a poster campaign showing it as a maiden aunt,

La Tante BBC

, whose initials stood for Bobard-Boniment-Corporation – the Corporation of Lies and Humbug.

On the surface, everyday life was still normal in some respects. Although Renée was technically Jewish under the German ordinances, her husband’s family was an old Huguenot one. The children had been brought up as Protestants and were not legally Jewish. Thus, a pass to be had for the asking enabled her daughter Françoise to cross the Demarcation Line in order to attend the convention of the Protestant Scouts in Nîmes.

Strip-searched when crossing the line between Langon and La Réole, Françoise was already naked and about to take off her second sock, in which was hidden a letter she was bringing across for an old family friend, when the German policewoman told her she could keep her socks on. Unknown to Françoise, among the vines exactly 2km away on the line was an unguarded door, through which several hundred local people had simply walked unmolested into the Free Zone.

Now that the Germans allowed only the owners of houses situated in the coastal zone to stay there, Baboushka had fled inland to the village of Sablé, still in the Occupied Zone, and was surprised how hard it was to find a hotel room. With the coast off-limits for holidays, inland hotels were full, any empty rooms taken by German soldiers billeted on the hoteliers. The couple running Baboushka’s hotel were both Pétainist and anti-Semitic, yet business was business, so they made a point of always addressing her by the non-Jewish part of her name, ‘Madame Robert’.

11

On July 11 Déat and Doriot launched La Légion des Volontaires Français contre le Bolchevisme (LVF), with Deloncle as president. Recognised by Darlan on 3 August, the movement had the support of the Institut Catholique, Monseigneur Jean Mayol de Lupé going so far as to enrol himself as chaplain-general with the SS rank of Sturmbannführer, greeting his Sunday congregation with, ‘

Heil Hitler! Et pieux dimanche, mes fils!’

(‘Heil Hitler and a devout Sunday!’). Among his spiritual sons were Abbés Verney and Lara, who volunteered as chaplains to accompany into Russia the LVF units hailed by Cardinal Baudrillart as ‘the finest sons of France’. Mistrusting the idea of French soldiers in German uniform, Hitler limited LVF numbers to 15,000. He need not have worried because although 173 recruiting offices were opened, of the 10,788 who volunteered in the next two years, only 6,429 passed the medical, such was the toll of food shortages on general health.

12

Doriot departed for the eastern front, doing his political career irredeemable harm by absenting himself from France for eighteen months.

Governments of the Third Republic had been preoccupied with the declining birth rate. Pétain’s regime took this one stage further. While elevating motherhood as a career and encouraging Mother’s Day national propaganda, the old marshal’s brand of national socialism also looked after the family unit, in which it had common cause with the Church. Three months after the Armistice, one of many magazine articles signed by him stated, ‘The rights of families precede and override those of the state and individual rights. The family is the essential unit of social structure.’

13

The strong Marian cult in the Church naturally approved. Smiling priests were photographed with children reciting prayers they had written asking Jesus to protect the marshal. The image of the Good Shepherd was applied to him and on 24 July 1941, the Church bestowed its final blessing on Pétain and all his works in a statement read out in every church: ‘We venerate the head of state and ask that all French citizens rally round him. We encourage our flock to take their places at his side in the measures he has undertaken in the three domains of family, work and fatherland.’

14

No head of state could have asked for more. On 12 August Pétain denounced as an ‘evil wind blowing through France’ those who refused to collaborate, saying, ‘In 1917 I ended the mutinies. In 1940 I put an end to the rout. Today, it is from yourselves that I wish to save you.’

15

On 13 August communist demonstrators came to blows in Paris with French police and German Feldgendarmerie units at Porte St-Denis and Porte St-Martin. The following day, sober bespectacled Pierre Pucheu, appointed Minister of the Interior by Darlan in July, expanded the Service de Police Anti-Communiste (SPAC) created by Daladier in 1939 by forming the ‘brigades spéciales’. The ambiguous title concealed a nationwide machinery for arresting and trying communists with no appeal system and only one verdict: death. Seeking to justify himself at his trial for collaboration in Algiers during 1944, Pucheu claimed that he had accepted the Interior Ministry under compulsion, and selected hostages to be shot from lists of known communists in order to spare the lives of ‘good Frenchmen’, but those who knew him at the time saw a man eaten hollow by the worm of ambition.

Former law student Albrecht Krause, a legally trained observer, arrived in Paris on the day of the demonstrations to take up his post on the staff of von Stulpnagel in Operationsabteilung 1A. While convalescing after being wounded in the chest near Leningrad, he had attended the trial in Strasbourg of nineteen Alsatian and French communist activists. After hearing Roland Freisler, president of the Nazi Volksgerischthof, ranting and raving against the accused, allowing neither them nor their lawyers to speak, Krause left the hearings appalled and was taken to lunch by the GOC Strasbourg in a smart hotel where they saw Freisler and his cronies enjoy a three-hour feast before returning to sentence the seventeen men to death and the single female defendant to life imprisonment. On the spot, Krause decided that pursuing his law studies under such a regime was impossible.