Village Affairs (13 page)

Authors: Miss Read

'Come and help me put these roses in water,' I said. 'I

intend to ignore that quite unnecessary last remark.'

'Hoity-toity,' said Amy, following me into the kitchen, and watching me start my flower arranging.

'Are you going to see Vanessa?'

'Yes, quite soon. James has to go to Glasgow on business, and we thought we'd have the weekend with them. There's one thing about being a Scottish laird. It seems that there are hosts of old loyal retainers to help with the cooking and housework. Why, Vanessa even has an under-nurse to help the monthly one! Can you imagine such luxury?'

'Would you take the matinee jacket I've just finished? It's pink, of course, but that's like life.'

'No bother at all,' said Amy. 'By the way, do you really want that red rose just there?'

'Why not?'

'It breaks the line.'

'What line?'

'Aren't you taking the eye down from that dark bud at the top to the base of the receptacle and below?'

'Not as far as I know. I was simply making sure that they were all in the water.'

Amy sighed.

'I do wish I could persuade you to come to the floral classes with me. It seems so dreadful to see you so ignorant of the basic skills of arrangement. You could really benefit with some pedestal work. Those roses call out for a pedestal.'

'At the price pedestals are, according to Mrs Mawne, these roses can go on calling out,' I said flatly. 'What's wrong with this nice white vase?'

'You're quite incorrigible,' said Amy, averting her eyes. 'By the way, how's Minnie Pringle?'

'In smashing form, as the music hall joke has it.'

I told her about some of Minnie's choicer efforts, particularly the extraordinary methods used for the drying of dusters.

'You won't believe this,' I told her, 'but last Friday she had upturned the vegetable colander on the draining board, and had draped a wet duster over that. Honestly, I give up!'

'Perhaps you won't have her much longer. I hear that Mrs Fowler has ejected Minnie's husband. My window cleaner says the rows could be heard at the other side of Caxley.'

My spirits rose, then fell again.

'But it doesn't mean that he'll come back to Springbourne necessarily, and in any case, Minnie will probably still need a job. I don't dare hope that she'll leave me.'

'He'll have to sleep somewhere,' Amy pointed out, 'and obviously his old home is the place.'

'Minnie might demand more money, though, and let him stay on sufferance,' I said, clinging to this straw like a drowning beetle, 'then she wouldn't need to come to me on Fridays.'

'I think you are going too fast,' said Amy, lighting a cigarette and inserting it into a splendid amber holder. 'It's a case of wishful thinking, as far as you are concerned. I imagine that he'll return to Minnie, make sure she's bringing in as much money as possible, and will sit back and pretend he's looking for work. Minnie really isn't strong enough to protest, is she?'

Sadly, I agreed. It looked as though I could look forward to hundreds of home-wrecking Friday afternoons.

'Mrs Coggs,' I said wistfully, 'is doing more charing now that Arthur's inside. I gather she's a treasure.'

'You shouldn't have been so precipitate in offering Minnie a job,' reproved Amy. 'Incidentally, Arthur's case comes up at Crown Court this week. It was in the local paper.'

'I missed that. Actually this week's issue was handed by that idiotic Minnie to Mrs Pringle to wrap up the chicken's scraps, before I'd read it.'

'Typical!' commented Amy, blowing a perfect smoke ring, an accomplishment she acquired at college along with many other distinctions, academic and otherwise.

'Well, if you've quite finished ramming those roses into that quite unsuitable vase,' said Amy, 'can I beg a glass of water?'

'I'll do better than that,' I told her, bearing my beautiful bouquet into the sitting-room. 'There's a bottle of sherry somewhere, if Minnie hasn't used it for cleaning the windows.'

AS always, everything seemed to happen within the last two weeks of term.

At the beginning of every school year, I make all sorts of good resolutions about being methodical, in time with returning forms and making out lists, arranging programmes well in advance and so on. I have a wonderful vision of myself, calm and collected, sailing through the school year's work with a serene smile, and accepting graciously the compliments of the school managers and the officials at the local education department, on my efficiency.

This blissful vision remains a mirage. I flounder my way through the multitudinous jobs that surround me, and can always still be far behind, particularly with the objectionable clerical work, when the end of the year looms up.

So it was this July. The village fête in aid of Church Funds, as usual, had to have a contribution from the school, and as Mrs Rose became less and less capable as the end of her time drew nigh, and more and more morose since the tiff with Mrs Pringle, I was obliged to work out something single-handed.

It is difficult to plan a programme which involves children from five to eleven taking part, but with all the parents present at the fête, and keen to see their own offspring in the limelight, it was necessary to evolve something.

After contemplating dancing, a play, a gymnastic display

and various other hoary old chestnuts, I decided that each of these activities needed more time and rehearsing than I could possibly manage. In the end I weakly fell back on folk songs, most of which the children knew already.

Mrs Rose gave half-hearted support to this proposal, and the air echoed each afternoon as we practised. Meanwhile, there were the usual end of term chores to do, and the heat continued, welcome to me, but inducing increasing langour in the children.

It was during this period that Arthur Coggs and his partners in crime appeared at Crown Court.

As Mr Willet had forecast, all the accused were given prison sentences. The brothers Bryant were sent down for three years and Arthur Coggs for two.

'Not that he'll be there all that time,' said Mr Willet. 'More's the pity. They takes off the time he's been in custody already, see, and if he behaves himself he'll get another few months cut off his spell inside. I reckons he's been lucky this time. We'll have him back in Fairacre before we've got time to turn round, darn it all!'

Mrs Coggs, it was reported, had gone all to pieces on hearing the sentence. Mrs Pringle told me the details with much relish.

'As a good neighbour,' she said, 'I lent that poor soul

The Caxley Chronicle

to read the result for herself, and I've never seen a body look so white and whey-faced as what she did! Nearly fell off of her chair with the shock,' said Mrs Pringle with evident satisfaction.

'Wouldn't it have been kinder to have told her yourself, if she'd asked?'

'I didn't trust myself not to break down,' responded the old

humbug smugly. 'A woman's heart's a funny thing, you know, and she loves that man of hers despite his little failings.'

'I should think,

little failings

hardly covers Arthur's criminal activities,' I said, but Mrs Pringle was in one of her maudlin moods and oblivious to my astringency.

'I was glad to see the tears come,' went on that lady. 'I says to her: "That's right! A good cry will ease that breaking heart!"

'Mrs Pringle,' I cried, 'for pity's sake spare me all this sentimental mush! Mrs Coggs knew quite well that Arthur would go to prison, and she knew he deserved it. If I'd been in her shoes, I'd have breathed a sigh of relief.'âMrs Pringle, cut short in the midst of her dramatic tale, looked at me with loathing.

'There's some,' she said, 'as has no feeling heart for the misfortunes of others. It's plain to see it would be useless to come to you in trouble, and I'm glad poor Mrs Coggs had my shoulder to weep on in her time of affliction. One of these fine days, you may be in the same boat,' she added darkly, and limped from the room.

Heaven help me, I thought, if that day should ever come.

As it happened, trouble did come, but I managed to cope, without weeping on Mrs Pringle's ample bosom.

I received a letter from the office, couched in guarded terms, about the authority's long-term policy of closing small schools which were no longer economic to run. It pointed out that Fairacre's numbers had dwindled steadily over the years, that the matter had been touched on at the last managers' meeting, and that local comment would be sought. It emphasised the fact that nothing would be done without thorough consultation with all concerned, and that this was simply a preparatory exploration of local feeling. Closure, of course, might never take place should numbers increase, or other circumstances make the school vital to the surroundings. But should it be deemed necessary to close, then the children would probably attend Beech Green School, their nearest neighbour.

A copy of the letter, it added, had been sent to all the managers.

I felt as though I had been pole-axed, and poured out my second cup of coffee in a daze.

The rooks were wheeling over the high trees, calling harshly as they banked and turned against the powder-blue morning sky. The sun glinted on their polished feathers, as they enjoyed the Fairacre air. How long should I continue to enjoy it I wondered?

By the time I had sipped the coffee to the dregs, I was feeling calmer. In a way, it is always better to know the worst, than to await tidings in a state of dithering suspense. Well, now something had happened. The rumours were made tangible. The ostrich on the merry-go-round had come to a stop in full view of all of us. Now we must do something about it.

I washed up the breakfast things, put down Tibby's mid-morning snack, washed my hands, and made my way across to the school.

Now what should I choose for our morning hymn? 'Oft in danger, oft in woe' might fit the case, or 'Fight the good fight' perhaps?

No, let's have something bold and brave that we could roar out together!

I opened the book at:

'Ye holy angels bright

Who wait at God's right hand' and looked with approval at the lines.

'Take what He gives, and praise Him still

Through good or ill, whoever lives.'

That was the spirit, I told myself, as the children burst in, breathless and vociferous, to start another day beneath the ancient roof which had looked down upon their parents and their grandparents at their schooling years before.

I guessed that the Vicar would pay me a visit, and before playtime he entered, holding his letter, and looking forlorn. The children clattered to their feet, glad, as always, of a diversion.

'Sit down, dear children,' said the Vicar, 'I mustn't disturb your work.'

That, I thought, is just what they want disturbed, and watched them settle down again reluctantly to their ploys.

'I take it you have had this letter too?'

'Yes, indeed.'

'It really is most upsetting. I know it stresses the point of there being no hurry in any of these decisions, nevertheless I feel we must call an extra-ordinary meeting of the managers, to which you, naturally, are invited, and after that I suppose we may need to have a public meeting in the village. What do you think?'

'See what the managers decide, but I'm sure that's what they will think the right and proper thing to do. After all, it's not only the parents, though they are the most acutely involved, but everyone in Fairacre.'

'My feelings exactly.'

He sighed heavily, and the letter which he had put on my

desk, sailed to the floor. Six children fell upon it, like starving dogs upon a crust, and it was a wonder it was not torn to shreds before the Vicar regained his property.

After this invigorating skirmish, they returned to their desks much refreshed. The clock said almost a quarter to eleven, and I decided that early playtime was permissible under the circumstances.

They clattered into the lobby and the clanging of milk bottles taken from the metal crate there, made a background to our conversation.

'You see there was some foundation for those rumours,' commented Mr Partridge. 'No smoke without fire, as they say.'

'It began to look ominous when the measuring started at Beech Green.' I responded 'And Mr Salisbury was decidedly cagey, I thought. Oh dear, I hope to goodness nothing happens! In a way, the very fact that it's going to be a long drawn-out affair makes it worse. I keep wondering if I should apply for a post elsewhere, before I'm too old to be considered.'

The Vicar looked shocked.

'My dear girl, you mustn't think of it! The very idea!

Of course,

you must stay here, and we shall all see that you do. That's why I propose to go back to the vicarage and fix a date for the managers' meeting as soon as possible.

'I do appreciate your support,' I said sincerely, 'it's just this ghastly hanging about. You know.

'The mills of God grind slowly

But they grind exceeding small."'

The Vicar's kind old face took on a look of reproof.

'It isn't God's mill that's doing the grinding,' he pointed out. 'It's the education office's machinery. And that,' he added vigorously, 'we must put a spoke in.'

If he had been a Luddite he could not have sounded more militant. I watched him cross the playground, with affection and hope renewed.

They say that troubles never come singly, and while I was still reeling under the blow of that confounded letter, I had an unnerving encounter with Minnie Pringle.

Usually, she had departed when I returned to my home after school on Fridays. I then removed the wet dusters from whatever crack-brained place Minnie had left them in, put any broken shards in the dustbin, and set about brewing a much-needed cup of tea, thanking my stars that my so-called help had gone home.

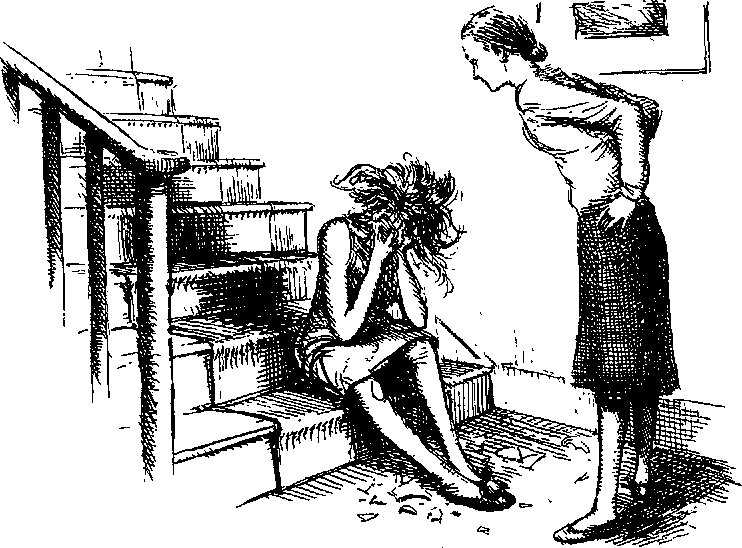

But on this particular Friday she was still there when I entered the house. A high-pitched wailing greeted me, and going to investigate I found Minnie sitting on the bottom stair with a broken disinfectant bottle at her feet.