Vietnam (15 page)

Authors: Nigel Cawthorne

Most downed airmen ended up in Hoa Lo, the old French colonial prison in Hanoi, which inmates dubbed the 'Hanoi Hilton'. It was made up of a series of compounds. Each got a nickname. When prisoners first arrived, they went to 'New Guy Village', then to 'Las Vegas' and 'Heartbreak Hotel' where they were tortured. 'Camp Unity' was the compound where prisoners were allowed to meet after December 1970: until then, they would have been held in solitary confinement.

From 1965 to 1967, some US prisoners were held a in compound called the 'Briarpatch', some thirty miles to the northwest of Hanoi. After 1967, they were moved to the 'Zoo' at Cu Loc. There were other compounds outside Hanoi such as 'Camp Faith', 'Skid Row' and Son Tay. There were other smaller compounds in Hanoi, including one in the old movie studio. After 1967, 'Alcatraz' housed the prisoners who had given their captors particular problems. A 'model' prison was also constructed for the cooperative prisoners in the grounds of the mayor's house, where they could be inspected by visiting dignitaries.

The most famous prisoner of war was John McCain, who went on to become a US Senator and ran unsuccessfully for the Republican presidential nomination in the 2000 election. During the Vietnam War, McCain was a Navy flier. His father, an admiral, was commander of all US forces in the Pacific. McCain was shot down over Hanoi in 1967 and badly injured. When the Vietnamese realised that their prisoner was the son of a high-ranking officer, they offered to return him. But McCain refused early release, fearing it would be used to embarrass the US government. He insisted that standard military procedures be followed and prisoners of war be returned in the order of their date of capture. As a result, McCain was held in solitary confinement and tortured frequently. He was returned in 1973 with the other prisoners after five and a half years in captivity. In 1982, he was elected to Congress as a Republican and in 1986 he became a US Senator for Arizona.

Time

magazine named him one of its 'Top 25 Most Influential People in America' in 1997.

Even though Rolling Thunder was intensified in 1967, the North Vietnamese were repeatedly offered an end to the bombing, if they would come to the conference table. They insisted that the bombing must end first. On 13 January, the US had to temporarily halt the bombing unilaterally during a controversy over civilian deaths following an air raid on the Yenvien marshalling yard. Nevertheless, after a truce for Tet, the lunar New Year, the US escalated the war yet again by permitting artillery bombardments of North Vietnamese territory and dropping mines in Northern rivers. In March, the USAF destroyed a steel works forty miles from Hanoi and the Thai government gave permission for B-52s to fly from their air bases, instead of coming all the way from Andersen Air Force Base on Guam in the Mariana Islands, a twelve-hour round trip. Even so, at a conference in Guam, Ky criticised US restraint, asking Johnson, 'How long can Hanoi enjoy the advantage of restricted bombing of military targets?'

In the South, nearly 180 fighter-bombers supported the US forces in Operation Junction City. In the battle at Ap Gu on 2 April, the Vietcong claimed to have downed twenty-two of them.

On 20 April, the port at Haiphong was bombed for the first time, while US Secretary of State Dean Rusk expressed 'regret' that civilian casualties might occur as a result of raids on 'essential military targets'. Five days later, US planes hit the British freighter

Dartford

in Haiphong harbor. But this did nothing to check the Pentagon's relentless escalation of the bombing. On 19 May central Hanoi was hit for the first time in an effort to take out the largest power plant in North Vietnam.

In August, President Johnson dropped most of the remaining restrictions on the bombing of the North, and North Vietnam became, essentially, a free-fire zone. US planes began bombing road and rail links in the Hanoi-Haiphong area and raids attacked targets just ten miles from the Chinese border. One Democrat congressman asked how the US would react to a Chinese bombing raid on Mexico that hit targets ten miles from the Rio Grande. Despite this Ronald Reagan, then governor of California, complained that too many 'qualified targets' were off-limits to bombing. Meanwhile, the USAF Chief of Staff General John P. McConnell told a Senate Committee that the graduated escalation of the bombing begun in 1965 was a mistake. Rather they should have taken out ninety-four key targets in the first sixteen days in one massive blow. Three days later, McNamara admitted that bombing the North had not materially affected the Communist's fighting capability, though Admiral Sharp claimed that it was causing Hanoi 'mounting logistic, management, and morale problems'. General Giap had his say in a Communist newspaper, declaring that President Johnson was using 'backward logic' if he thought that bombing the North would ease the pressure on the South. Nevertheless, the Senate Committee called for massive bombing raids on Haiphong. Renewed raids were mounted on Hanoi and Haiphong, and on the dock area of Cam Pha. But by then the North Vietnamese MiGs were airborne again, this time flying from airfields in China and out of bounds to US air raids. Between 23 and 30 October, during heavy attacks on bridges, airfields and power plants in the Hanoi-Haiphong region thirteen US aircraft were shot down.

While Rolling Thunder was escalating, a huge tonnage of bombs was being dropped on South Vietnam. The statistics looked impressive. The US won numerous victories on the battlefield, inflicting huge losses on the enemy. In Operation Wheeler/Wallowa, the American Infantry Division claimed a body count of 8,188. But somehow this did not sap the Communists' will to fight. Meanwhile, US casualties continued to mount. On 11 December 1967, Johnson declared that 'our statesmen will press the search for peace to the corners of the earth' and suggested that peace talks be held on board a neutral ship at sea. Hanoi rejected this idea four days later.

However, the Christmas truce brought a ray of hope. The North Vietnamese Foreign Minister Nguyen Du Trinh announced that North Vietnam was willing to open talks if the US halted the bombing. But this was a ruse to lull the US authorities into a false sense of security. The Hanoi government was already planning the biggest offensive in the war so far – the offensive that would finally convince the American people that the war was unwinnable.

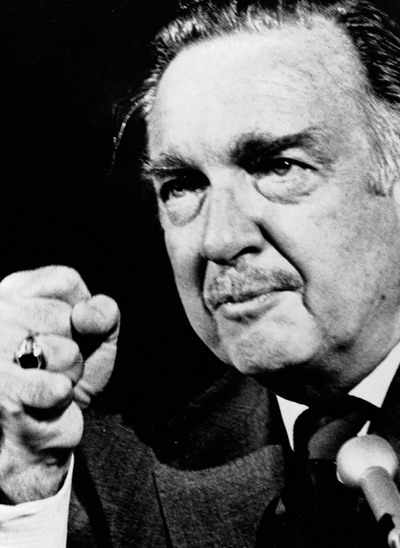

Walter Cronkite testifies on freedom of the press before a Senate subcommittee in Washington, 30 September 1971.

THE UNWINNABLE WAR

AS 1967 DREW TO A CLOSE

, the American people were told they were winning the war. On 17 November President Johnson told the television audience, 'We are inflicting greater losses than we're taking... We are making progress'.

Four days later, General Westmoreland told the press, 'I am absolutely certain that, whereas in 1965 the enemy was winning, today he is certainly losing'.

However, there was one man who was not convinced. His name was Robert McNamara, and as Secretary of Defense, he was well placed to judge: even a cursory look at the war would have shown that the US was in trouble. Despite repeated escalations in the American commitment, men and matériel continued to flow down the Ho Chi Minh trail. The Communists seemingly suffered no shortage of weapons or ammunition. The Vietcong mounted attacks throughout the country, seemingly at will. They even attacked well-protected air bases and destroyed planes. The NVA fought massed engagements, then withdrew and reformed. American forces made repeated sweeps through hostile areas, only to find them reoccupied by the VC as soon as they were gone. With no front lines, no territory was being taken. American forces seemed to be committed to an endless round of piecemeal battles that never proved to be big enough to be decisive.

As Secretary of Defense in both the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, McNamara was one of the most relentless advocates of the war. It was McNamara who had presented the evidence of North Vietnamese aggression to Congress after the Gulf of Tonkin Incident in 1964. In February 1965, he backed the National Security Council's proposal for 'retaliatory' air strikes against the North and backed Westmoreland's repeated demands for more troops. But in October 1966, McNamara went to Vietnam. It was his eighth trip, but the first for over a year. On 14 October, he sent a memorandum to President Johnson suggesting 'stabilising' the bombing campaign. In McNamara's opinion it had been a costly failure. Millions of tons of bombs had been dropped with no marked effect on the economy of the North, Hanoi's commitment to the war, or the infiltration into the South. The hi-tech McNamara Line was to be the alternative to bombing to prevent infiltration. He also recommended that there should be no further increase in troops and a greater commitment to 'pacification'. Only his idea for the McNamara Line – which soon proved to be another costly failure – was accepted. His other views found no support outside the State Department. But again in March 1967, he suggested limiting bombing to staging areas and infiltration routes.

McNamara was an alumnus of Harvard Business School. Regarded as a 'whizz kid', he was hired by the Ford Motor Company, where he set about the institution of strict cost-accounting methods and rose to become the first person outside the family to become the company's president, quitting after a month to join the Kennedy administration as Secretary of Defense. With his business school background, he had been taught to analyse problems dispassionately and follow the conclusion no matter where it led. In May 1967, the Department of Defense's Systems Analysis Office did the figures on the war and realised that the Communists were controlling the frequency, number, size, length and intensity of engagements. That way they controlled their casualties, which they were keeping just below their birth rate. This was a winning strategy. According to the DoD's report:

The VC and NVA started the shooting in over 90 per cent of company-sized firefights. Over 80 per cent began with a well-organised enemy attack. Since their losses rise – as in the first quarter of 1967 – and fall – as they have done since – with their choice of whether or not to fight, they can probably hold their losses to about two thousand a week regardless of our force levels. If their strategy is to wait us out, they will control their losses to a level low enough to be sustained indefinitely, but high enough to tempt us to increase our forces to the point of US rejection of the war.

As long as the North Vietnamese government maintained their people's will to fight – and there were no signs of a crack in the Communists' morale – this strategy meant they could fight forever. The same could not be said of America. Public opinion, although hugely in favour of the war at the outset, was now fragmenting. Huge anti-war demonstrations were taking place across America. Even in Congress things were looking bad. The influential chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, William Fulbright, who had initially been a keen supporter of the war, had turned fervently against it, advocating talks between Saigon and the Vietcong.

To McNamara the war now seemed unwinnable. As it dragged on it was bound to become increasingly unpopular. In June 1967, he instituted a study of 'The History of the US Decision Making Process in Vietnam' – which would be leaked to the newspapers as the 'Pentagon Papers' – and in August he outlined his increasingly dovish views to the hawkish Preparedness Subcommittee of the Senate Armed Services Committee, who strongly favoured a further escalation in the bombing.

In a Draft Presidential Memorandum of 17 November 1967, McNamara recommended curtailment of the war rather than escalation. In his conclusion, he wrote, 'The picture of the world's greatest superpower killing or seriously injuring a thousand noncombatants a week, while trying to pound a tiny backward nation into submission on an issue whose merits are hotly disputed is not a pretty one'. This could have come straight from an anti-war pamphlet. It was a final break with Johnson's hardline policy. Close to a nervous breakdown, McNamara tendered his resignation in November 1967. After waiting for a suitable interval to elapse before leaving the administration, on 29 February, 1968 he quit to become president of the World Bank. The official line was still that the war could be won, if Westmoreland was given enough men. By the end of 1967 there were half-a-million American troops in Vietnam and Senator Eugene McCarthy announced he would run for the presidency on an anti-war ticket. But neither the hawks or the doves predicted what would happen next.

They did know that something was going to happen though. For six months there had been reports that Hanoi was planning a major offensive in the South. The truce for Christmas and New Year was punctuated by frequent outbreaks of violence and Ho Chi Minh announced that the forthcoming year would bring great victories for the Communist cause.

On 21 January 1968, four North Vietnamese Army infantry divisions, supported by two armoured regiments and two artillery regiments – 40,000 men in all – began converging on Khe Sanh, a US Marine Corps base just south of the DMZ. Westmoreland believed that the North Vietnamese intended to grab the northernmost provinces of South Vietnam, prior to opening peace negotiations – just as they had moved against the French at Dien Bien Phu to buttress their bargaining position at the Geneva Peace Conference in 1954. Peace feelers were out at that time. At a reception in Hanoi on 30 December 1967, less than a month earlier, North Vietnam's Foreign Minister Nguyen Duy Trinh dropped most of North Vietnam's preconditions on talks and said that Hanoi would enter peace talks with the US if the bombing was halted.