Vespasian: Tribune of Rome (28 page)

Read Vespasian: Tribune of Rome Online

Authors: Robert Fabbri

T

HRACIA

, S

PRING AD

26

‘W

HAT

’

S THAT ARSEHOLE

up to now?’ Magnus spat as he looked with disgust towards Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo, the commander of the reinforcement column. ‘If we change direction again today I’m going to mutiny.’

‘You need to be under military discipline to mutiny,’ Vespasian reminded his friend as he watched Corbulo engage in another heated exchange with their local guides. ‘And seeing as you’re here masquerading as my freedman, and therefore a civilian, I think that anything you say or do will be ignored, especially by someone as well-born and arrogant as Corbulo.’

Magnus grunted and removed his conical felt cap, the

pileus

, the sign of a freedman, and wiped his brow. ‘Pompous arsehole,’ he muttered.

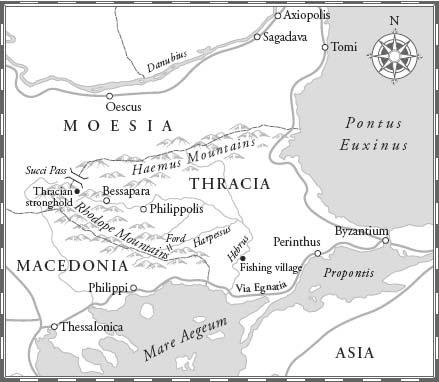

They had crossed the border from the Roman province of Macedonia into the client kingdom of Thracia five days earlier. For three days, following the course of the Via Egnatia, they’d marched through the budding orchards and the newly sown cornfields of the narrow coastal plain wedged between the forbidding, cloud-strewn bulk of the southern arm of Rhodope mountain range to the north, and the azure blue of the beautiful but treacherous Thracian sea, sparkling in the warm spring sun, to the south.

Corbulo had received orders, waiting for him at Philippi on the Macedonian border, to rendezvous as soon as possible with Poppaeus Sabinus’ army at Bessapara, on the Hebrus River, in the

northwest of the client kingdom, where the northern arm of the Rhodope range abuts the Haemus Mountains. It was here that Poppaeus had the Thracian rebels pinned down in their hilltop stronghold, having defeated their main army in battle about fourteen days before. Corbulo had cursed his luck. He had tried to find out the details of the battle, but the messenger had already departed for Rome to bring news of the victory to the Emperor and Senate.

Being a young and ambitious nobleman he was taking the request for speed very seriously, anxious to arrive before the rebellion was completely crushed and his chances of glory diminished.

They had met their guides and left the road at the eastern end of the Rhodope range, and were now heading northeast through its trackless foothills to pass around to the northern side of the mountains and follow them, northwest, to their destination. They were in the lands of the Caeletae, a tribe that had stayed loyal to Rome and its puppet, King Rhoemetalces, mainly out of hatred for their northern neighbours the Bessi and the Deii, who had revolted the previous year against conscription into the Roman army.

Vespasian grinned at Magnus as they watched Corbulo bellow at the Caeletaean guides, turn his horse and head back down the column towards where they were stationed, at the head of the first cohort of 480 legionary recruits.

‘I think our esteemed leader is just about to push another tribe into rebellion,’ he said, watching the red-faced military tribune approach past the vanguard of 120 auxiliary Gallic cavalry. ‘If he carries on like that we’ll find ourselves dangling in wooden cages over their sacred fires.’

‘I thought it was just the Germans and Celts who did that,’ Magnus replied, easing his travel-weary behind in his saddle.

‘I expect that these barbarians have just as nasty a way of amusing themselves with their captives; let’s hope that Corbulo’s arrogance doesn’t drive them to practise on us.’

‘Tribune,’ Corbulo barked, pulling up his horse next to Vespasian, ‘we are stopping here for the night; those ginger-haired sons of fox bitches are refusing to go any further today. Have the men construct a camp.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘And, tribune—’ Corbulo peered at Vespasian over the long, pronounced nose that dominated his thin, angular face ‘—tell Centurion Faustus to double the guard tonight. I don’t trust those bastards, they seem to do everything possible to hinder our progress.’

‘I thought they were loyal to Rome.’

‘The only loyalty these savages have is to their filthy tribe’s rapacious gods. I wouldn’t trust them with their own grandmothers.’

‘We do seem to be taking a very circuitous route.’

‘They’re in no hurry to reach our objective. Every time I insist that we start to head northwest they find an excuse after a mile or so to turn back to the northeast. It’s as if they want to lead us somewhere completely different.’

‘Here, for example?’ Vespasian looked up at the rocky hills to his left, and then down to the thick pine forest, which stretched as far as he could see, below them. ‘This is not a place I would choose for a camp, far too enclosed.’

‘My point exactly, but what to do, eh? There’s little more than three hours to sundown, and without the guides we may not find anywhere better, so we’re stuck here. At least there’s plenty of timber, so get the men to it, I want a stockade camp tonight; we’ll act as if we’re in hostile territory.’

Vespasian watched his superior move off down the column. He was seven years older than Vespasian and had served on Poppaeus’ staff for the past three years; before that he had been on the Rhine frontier for a year. Although he too came from a rustic background, his family had had senatorial rank for the past two generations and

he behaved with the arrogance of someone born into a privileged life. Being sent back to Italia along with Centurion Faustus, the

primus pilus

or senior centurion of the IIII Scythica, to pick up the column of recruits, and thus miss the start of the season’s campaigning, had hurt his pride. His subsequent impatience with the smallest of errors or misdemeanours by any of the hapless new recruits had resulted in many a flogging and one execution over the seventy days that they had been on the march. He was, as Magnus had rightly observed, an arsehole, but even Vespasian with his limited experience could see that his military instincts were correct, and he turned to relay his orders.

‘Centurion Faustus!’

‘Sir!’

Centurion Faustus snapped to attention with the rattle of

phalerae

, metal disc-like decorations worn on a harness over his mail shirt, awarded to him over his twenty-two years of service. The traverse white horsehair plume on his helmet stood as rigid as its owner.

‘Have the men construct a stockade camp, and set a double guard.’

‘Yes, sir!

Bucinator

, sound “Prepare camp”.’

The signaller raised the four-foot-long

bucina

to his lips and blew a series of high notes through the thin, bell-ended horn, used for signals within camp. The effect was immediate: the two cohorts of raw legionaries unshouldered their pack-poles and

pila

and then, guided by the vine canes of the centurions and the shouts of their

optiones

, the centurions’ seconds in command, were sorted into fatigue parties; some for trench-digging, some for soil-packing and some for stake-cutting. The auxiliary Gallic cavalry turmae from the front and the rear of the column formed up in a defensive screen to protect the men as they worked. Beyond them smaller units of Thessalian light cavalry and foot archers patrolled the surrounding

countryside. The camp servants and slaves offloaded the baggage, corralled the animals and levelled the ground, whilst the engineers paced out and marked up the line of the square palisade and the position of each of the two hundred

papiliones

, eight-man tents, within it.

It took only a few moments for the marching column to convert itself into a hive of industry. Every man fell into his allotted task, with the exception of the dozen Thracian guides who squatted down on their haunches and pulled their undyed woollen cloaks around their shoulders and their strange fox-skin hats over their ears against the cooling mountain air. They watched with sullen eyes, murmuring to one another in their unintelligible tongue, as the camp began to take shape.

By the time the sun had set the exhausted legionaries had started to cook their evening meal within the security of the 360-foot-square camp. Each man had either dug just over four feet of trench, five feet wide and three feet at its deepest, piling the spoil up two feet high on the inside for others to pack down, or they had cut and shaped enough five-foot stakes to cover the same length; and all this after marching sixteen miles over rough ground. They hunched in groups of eight, over smoky fires by their leather tents, complaining about the arduousness of their new military lives. The odour of their stale sweat masked the blander smell of the rough military fare that bubbled in their cooking pots. Not even their daily wine ration could produce any laughter or light-hearted banter.

Vespasian sat outside his tent listening to their grumbling as Magnus boiled up the pork and chickpea stew that was to be their supper. ‘I’ll wager there’s more than a few of them regretting joining the Eagles at the moment,’ he observed, taking a slug of wine.

‘They’ll get used to it,’ Magnus said, chopping wild thyme into the pot. ‘The first ten years are the hardest – after that it slips by.’

‘Did you serve the full twenty-five?’

‘I joined up when I was fifteen and did eleven years with the Legio Quinta Alaudae on the Rhine then transferred to the Urban Cohort; they only have to serve sixteen so I was lucky – I was out after a further five. I never made it to optio, though; mainly because I can’t write, although regularly getting busted for fighting didn’t help either. When I was discharged four years ago, it seemed sensible to make a virtue out of a vice so I became a boxer. The money’s better, but it tends to hurt more.’ He rubbed one of his cauliflower ears to emphasise the point. ‘Anyway, these whippersnappers are only moaning because it’s the first time they’ve had to build a full camp after a day’s march; they’ll get used to it after a season in the field. If they survive, that is.’

Vespasian conceded the point; since they had joined the column, late, ten miles outside Genua, they had covered twenty miles a day along proper roads within the safety of Italia, pitching camp wherever they pleased until they had reached the port of Ravenna. From there, after a long wait for the transport ships, they had crossed the Adriatic Sea and sailed down past Dalmatia to Dyrrachium, on the west coast of the province of Macedonia. Here they picked up the Via Egnatia and marched across Macedonia, only ever setting pickets around their camps. This was the first night that they could be said to be in some sort of danger. The men, many of them no older than him, would soon learn that it was better to be tired and safe in a camp than fresh and dead in an open field.

He turned his mind back to the day that he and Magnus had joined the column. Marius and Sextus had put them ashore, with their horses, just west of Genua, and then, before making their way back to Rome, had sailed the small ship into the harbour, under cover of night, to abandon it to be reclaimed some day by its rightful owner. He and Magnus had ridden across country to within a mile of the recruiting depot outside the town’s walls. There they had waited for two days in the overlooking hills for the column’s

departure. They had shadowed it along the Via Aemelia Scauri until they were sure that there were no Praetorians travelling with it, and then had caught up with it as if they had just come from Genua. The bollocking that he had received from Corbulo for his late arrival had been excruciating. However, it didn’t overshadow the relief that he had felt at being safely on his way out of Italia and, hopefully, out of the reach of Sejanus and his henchmen.

Vespasian sighed and contemplated the irony that the further he got from someone who would kill him the further he would be from someone who would love him. He fingered the good-luck charm around his neck that Caenis had given him as they had said goodbye and recalled her beautiful face and intoxicating scent. Magnus brought him out of his reverie.

‘Get this down you, sir,’ he said, handing him a bowl of steaming stew. It smelt delicious and, realising just how hungry he was, Vespasian started to eat with relish.