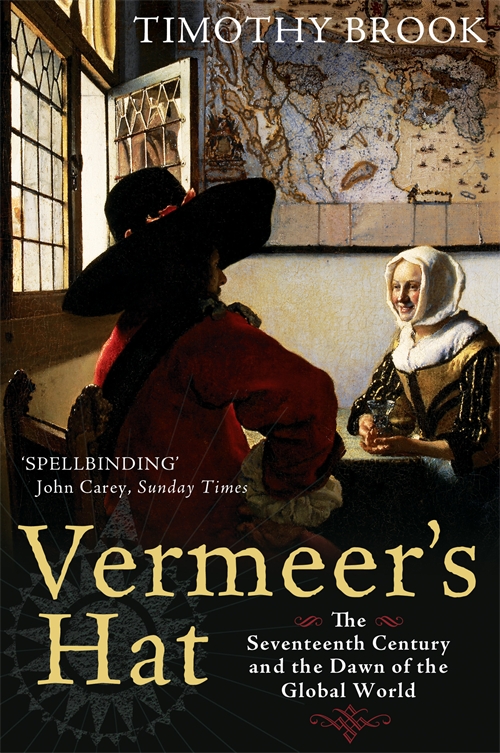

Vermeer's Hat

Authors: Timothy Brook

VERMEER’S HAT

‘This is a spellbinding book ... starting from details in five of Vermeer’s paintings, Brook takes readers on a series of

brilliantly circuitous mystery tours that reveal the savagery on which western civilisation was built.’ John Carey,

Sunday Times

‘Original and stimulating ...

Vermeer’s Hat

is a jewel of a study of two distinct yet intertwined worlds, feeling their way together towards modernity.’

London Review of Books

‘Brook takes his readers on a journey that encompasses Chinese porcelain and beaver pelts, global temperatures and firearms,

shipwrecked sailors, silver mines and Manila galleons. A book full of surprising pleasures.’ Jonathan Spence, author of

The Search for Modern China

‘In Brook’s hands, Vermeer’s paintings really do become windows on the past, illuminating a fascinating period in which the

world was being remade by global trade.’ Tom Standage, author of

A History of the World in Six Glasses

‘Thanks to Brook’s roving and insatiably curious gaze, Vermeer’s small scenes widen onto the broad panorama of world history

... a more entertaining guide to world history – and to Vermeer – is difficult to imagine.’ Ross King, author of

The Judgment of Paris

,

Michelangelo and the Pope's Ceiling

and

Brunelleschi’s Dome

TIMOTHY BROOK is Principal of St John’s College at the University of British Columbia, and holds the Shaw Chair in Chinese

Studies at Oxford University. He is the author of many books, including the award-winning

Confusions of Pleasure.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Quelling the People: The Military Suppression of the Beijing Democracy Movement

Praying for Power: Buddhism and the Formation of Gentry Society in Late-Ming China

Culture and Economy: The Shaping of Capitalism in Eastern Asia

(with Hy Van Luong)

Civil Society in China

(with B. Michael Frolic)

The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China

Documents on the Rape of Nanking

China and Historical Capitalism

(with Gregory Blue)

Nation Work: Asian Elites and National Identities

(with Andre Schmid)

Opium Regimes: China, Britain, and Japan, 1839–1952

(with Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi)

The Chinese State in Ming Society

Collaboration: Japanese Agents and Chinese Elites in Wartime China

Death by a Thousand Cuts

(with Jérôme Bourgon and Gregory Blue)

VERMEER’S HAT

The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn

of the Global World

TIMOTHY BROOK

This paperback edition published in 2009

First published in Great Britain in 2008 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London EC1R 0JH

First published in the United States of America by

Bloomsbury Press, New York

Copyright © Timothy Brook, 2008, 2009

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Bookmarque Ltd, Croydon, Surrey

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN: 978-1-84765-254-6

For Fay

Our arrivals at meaning and at value are momentary pauses in the ongoing dialogue with others from which meaning and value

spring.

—Gary Tomlinson,

Music in Renaissance Magic

CONTENTS

1: Johannes Vermeer,

View of Delft

(Mauritshuis, The Hague)

2: Johannes Vermeer,

Officer and Laughing Girl

(Frick Collection, New York)

3: Johannes Vermeer,

Young Woman Reading a Letter at an Open Window

(Gemäldegalerie, Dresden)

4: Johannes Vermeer,

The Geographer

(Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt-am-Main)

5: A plate from the Lambert van Meerten Museum of Delft (Gemeente Musea Delft)

MAPS

T

HE SUMMER I was twenty, I bought a bicycle in Amsterdam and cycled southwest across the Low Countries on what would be the

final leg of a journey that took me from Dubrovnik on the Adriatic to Ben Nevis in Scotland. I was on my second day out, pedaling

across the Dutch countryside, when the light began to fade and the late-afternoon drizzle blowing in off the North Sea turned

the road under my tires slick. A truck edged me too close to the verge, and my bicycle went over into the mud. I was not hurt,

but I was soaked and filthy and had a bent fender to straighten. Without the shelter of a bridge, which was my usual hobo’s

recourse in bad weather, I knocked at the door of the nearest house to ask for a few moments out of the rain. Mrs. Oudshoorn

had watched my spill from her front window, which is where I guessed she spent many a long afternoon, so I was not altogether

a surprise when she opened her door a crack and peered out at me. She hesitated for a brief moment, then put caution aside

and opened the door wide so that this bedraggled young Canadian could come inside.

All I wanted was to stand for a few minutes out of the rain and pull myself together, but she wouldn’t hear of it. She poured

me a hot bath, cooked me dinner, gave me a bed to sleep in, and pressed on me several of her dead husband’s things, including

a waterproof coat. The next morning, as sunlight poured over her kitchen table, she fed me the best breakfast I ever had eaten

and chuckled slyly about how angry her son would be if he ever found out she’d taken in a complete stranger, and a man at

that. After breakfast she gave me postcards of local sites to take as mementos and suggested I go see some of them before

climbing back on my bicycle and getting back on the road. The sun was shining that Sunday morning, and there was nowhere I

had to be, so out I went for a stroll and a look. Her town has stayed with me ever since. Mrs. Oudshoorn gave me more than

the hospitality of her home. She gave me Delft.

“A most sweet town, with bridges and a river in every street,” is how the London diarist Samuel Pepys described Delft when

he visited in May 1660. The description perfectly fit the town I saw, for Delft has remained largely as it looked in the seventeenth

century. Its cobbled streets and narrow bridges were dappled that morning by galleon-shaped clouds scudding in from the North

Sea a dozen kilometers to the northwest, and the sunlight reflecting off the canals lit up the brick façades of the houses.

Unlike that far grander canal city, Venice, which Italians built up from the surface of the sea on wooden pilings driven into

tidal sandbars, the Dutch built Delft below sea level. Dikes held back the North Sea, and water sluices were dug to drain

the coastal fens. This history resides in its name,

delven

being the Dutch word for digging. The main canal running the length of the western part of the town is still called the Oude

Delft, the Old Sluice.

Memories of the seventeenth century are peculiarly present in the two great churches of Delft. On the Great Market Square

is Nieuwe Kerk, the New Church, so named because it was founded two centuries after the Oude Kerk, the Old Church on the Oude

Delft canal. Both great buildings were built and decorated as Catholic churches, of course (the Old Church in the thirteenth

century, the New Church in the fifteenth), though they did not remain so. The light coming through the clear glass in the

windows and illuminating their interiors bleaches out that early history in favor of what came later: the purging of Catholic

idolatry, including the removal of stained glass in the 1560s, which was part of the Dutch struggle for independence from

Spanish rule, and the fashioning of Protestant gathering places of almost civil worship. The floors of both churches belong

quite securely to the seventeenth century, for they are covered with inscriptions marking the graves of the wealthier citizens

of seventeenth-century Delft. People in those days hoped to be buried as close as possible to a holy place, and better than

being buried beside a church was to be interred underneath it. Many of the numerous paintings done of the interiors of these

two churches show a lifted paving stone, occasionally even gravediggers at work, while other people (and dogs) go about their

business. The churches kept registers of where each family had its grave, but most of the graves bear no written memorial.

Only those who could afford the cost had the stones laid over them inscribed with their names and deeds.

It was in the Old Church that I came upon one stone inscribed neatly and sparely:

JOHANNES VERMEER

1632–1675. I had stumbled

upon the last remains of an artist whose paintings I had just seen and admired in the Rijksmuseum, the national museum in

Amsterdam, a few days earlier. I knew nothing about Delft or Vermeer’s connection to the town. Yet suddenly there he was in

front of me, awaiting my notice.

Many years later I learned that this paving stone had not been placed over his grave when he died. At that time, Vermeer was

not a person of sufficient importance to deserve an inscribed gravestone. He was just a painter, an artisan in one of the

fine trades. It is true that Vermeer was a headman of the artisans’ guild of St. Luke, and that he enjoyed a position of honor

in the town militia—though that was a distinction he shared with some eighty other men in his neighborhood. Even if there

had been money on hand when he died, which there wasn’t, this status did not justify the honor of an inscription. Only in

the nineteenth century did collectors and curators come to think of Vermeer’s subtle and elusive paintings as the work of

a great artist. The stone there now was not laid until the twentieth century, put down to satisfy the many who, unlike me,

knew he was there and came to pay their respects. This slab does not actually mark the place where Vermeer was buried, though,

since all the paving stones were taken up and relaid when the church was restored following the great fire of 1921. All we

know is that his remains are down there somewhere.

Nothing else of Vermeer’s life in Delft has survived. We know that he grew up in his father’s inn off the Great Market Square,

and that he lived most of his adult life in the house of his mother-in-law, Maria Thins, on the Oude Langendijck, or Old Long

Dike. This was where he surrounded himself with an ever-growing brood of little children downstairs; painted most of his pictures

upstairs; and died suddenly at the age of forty-three, his debts mounting and his wellspring of inspiration gone dry. The

house was pulled down in the nineteenth century. Of Vermeer’s life in Delft, nothing tangible is left.

The only way to step into Vermeer’s world is through his paintings, but neither is this possible in Delft. Of the thirty-five

paintings that still survive (a thirty-sixth, stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston in 1990, is still

missing), not one remains in Delft. They were sold after he died or carted to auctions elsewhere, and now are dispersed among

seventeen different galleries from Manhattan to Berlin. The three closest works are in the Mauritshuis, the royal picture

gallery in The Hague. These paintings are not far from Delft—The Hague was four hours away by river barge in the seventeenth

century but is now only ten minutes by train—but they are no longer where he painted them. To view a Vermeer, you have to

be somewhere other than Delft. To be in Delft, you have to forego the opportunity to look at a Vermeer.

Any number of reasons could be introduced to explain why Vermeer had to have come from Delft, from local painting traditions

to the character of the light that falls on the town. But these reasons do not allow us to conclude that Vermeer would not

have produced paintings just as remarkable had he lived somewhere else in Holland. Context is important, but it doesn’t account

for everything. By the same token, I could put forward any number of reasons to explain why a global history of the intercultural

transformations of seventeenth-century life must start from Delft. But they wouldn’t convince you that Delft was the only

place from which to begin. The fact of the matter is that nothing happened there that particularly changed the course of history,

except possibly art history, and I won’t try to claim otherwise. I start from Delft simply because I happen to have fallen

off my bike there, because Vermeer happened to have lived there, and because I happen to enjoy looking at his paintings. So

long as Delft does not block our view of the seventeenth-century world, these reasons are as good as any for choosing it as

a place to stand and consider the view.

Suppose I were to choose another place from which to tell this story: Shanghai, for instance, since my travels took me there

several years after that first visit to Delft and led to my becoming a historian of China? It would suit the design of this

book, in fact, since Europe and China are the two poles of the magnetic field of interconnection that I describe here. How

much would choosing Shanghai over Delft change the story I am about to tell? It’s possible it would not change a great deal.

Shanghai was actually rather like Delft, if we want to look for similarities below the obvious differences. Like Delft, Shanghai

was built on land that had once been under the ocean, and it depended on water sluices to drain the bogs on which it rests.

(The name Shanghai, which could be translated as On the Ocean, is in fact an abbreviation of Shanghaibang, Upper Ocean Sluice.)

Shanghai similarly was a walled city (though it was walled only in the mid-sixteenth century to protect it against raiders

from Japan). It was crisscrossed with canals and bridges and had direct water access to the ocean. The marketing center for

a productive agricultural economy built on the reclaimed land, it too anchored an artisanal network of commodity production

in the surrounding countryside (cotton textiles in this instance). Shanghai did not have the urban bourgeoisie whom (and for

whom) Vermeer painted, nor perhaps quite the same level of cultivation and sophistication. Its most prominent native son (and

Catholic convert) Xu Guangqi complained in a letter of 1612 that Shanghai was a place of “vulgar manners.” Yet Shanghai’s

wealthy families engaged in practices of patronage and conspicuous consumption, which included buying and showing paintings,

that seem rather like what the merchant elite of Delft were doing. An even more striking coincidence is that Shanghai was

the birthplace of Dong Qichang—the greatest painter and calligrapher of his age—who transformed painting conventions and laid

the foundations of modern Chinese art. It makes no sense to call Dong the Vermeer of China, or Vermeer the Dong of Holland;

but the parallel is too curious to leave unmentioned.

The similarities between Delft and Shanghai may seem superficial when we consider their differences. There was, first of all,

the difference of scale: Delft at mid-century had only twenty-five thousand residents, ranking sixth among Dutch cities, whereas

Shanghai before the famines and disorder of the 1640s administered an urban population well over twice that number and a rural

population of half a million. More significant were the differences in their political contexts: Delft was an important base

for a newly emerging republic that had thrown off the Hapsburg empire of Spain, whereas Shanghai was an administrative seat

within the secure control of the Ming and Qing empires.

1

Delft and Shanghai must also be distinguished in terms of the state policies that regulated interactions with the outside

world. The Dutch government was actively engaged in building trade networks stretching around the globe, whereas the Chinese

government maintained an on-again, off-again policy of restricting foreign contact and trade (a policy that was much debated

within China). These differences are significant, but if I treat them lightly, it is because they do not much affect my purpose,

which is to capture a sense of the larger whole of which both Shanghai and Delft were parts: a world in which people were

weaving a web of connections and exchanges as never before. This story stays largely the same, regardless of where one begins

telling it.

Choosing Delft over Shanghai has something to do with what has survived. When I fell off a bicycle in Delft, I stepped into

a memory of the seventeenth century. Not so when you fall off a bicycle in Shanghai. The past there has been so thoroughly

obliterated by first colonialism, then state socialism, and most recently global capitalism, that the only doors that actually

open onto the Ming dynasty are on library shelves. A wisp of memory lingers in the little streets around Yuyuan, the Garden

of Ease in the heart of what used to be the old city. This garden was founded at the end of the sixteenth century as a retirement

gift for the builder’s father, but around it grew up a small public gathering area where, among other things, artists came

to hang their works to sell. But the area has been so thoroughly built up in the intervening centuries that there is little

to betray what might have existed in the Ming dynasty.