Vegetable Gardening (65 page)

Harvesting cole crops

If all goes well, cole crops should be ready to eat after a few months. However, be sure to check the days to maturity for the varieties you choose. In this section, I share some tips to help you get the best harvests.

Broccoli

Harvest broccoli by cutting the main head when the flower buds are still tightly clustered together without any signs of blossoming. Even if the head is smaller than you would like it to be, cut it now. After the yellow flowers open, the flavor turns bitter. If you leave a few inches of the main stem on the plant, many broccoli varieties respond by growing side branches that produce little heads (see Figure 9-3). Keep harvesting, and the broccoli keeps producing! When you harvest the side shoots, cut the shoot back to the main stem. Doing so creates fewer, but larger side shoots that are easier to use.

Brussels sprouts

Brussels sprouts taste best after cool weather helps turn some of their carbohydrates into sugars. Following a frost, pick off the marble-sized sprouts from the bottom of the plant first, moving up the stalk. The more sprouts you pick from below, the larger the sprouts above will get. Pull off the lower leaves for easier picking.

To make the sprouts mature faster, snip off the top few inches of the plant once sprouts have formed on the bottom 12 inches of the stalk.

To make the sprouts mature faster, snip off the top few inches of the plant once sprouts have formed on the bottom 12 inches of the stalk.

Figure 9-3:

Side shoots on the broccoli plant keep the harvest coming.

Because Brussels sprouts tolerate temperatures into the 20s, you can harvest right into New Year's in some areas. I've picked frozen sprouts off plants for Christmas, and they tasted great. The flavor actually gets sweeter with cool temperatures! Just cook and eat them immediately; if you try to store them, they'll rot.

Cabbage

Harvest cabbage heads when they're firm when squeezed. By periodically squeezing your cabbages through the growing season, you'll be able to tell when they're firm. (Don't worry — they won't mind!) To harvest, cut the head from the base of the plant with a sharp knife. When harvesting early-maturing varieties in summer, don't dig up the plants. Cabbages have the ability to grow smaller side heads on the plant after the main head is harvested; you harvest these side heads the same way that you do the main head.

Sometimes, cabbage heads split before you can harvest them.

Sometimes, cabbage heads split before you can harvest them.

Splitting

occurs when the plant takes up too much fertilizer or water, especially around harvest time. This "overdose" causes the inner leaves to grow faster than the outer leaves, splitting the heads. Harvest splitting heads as soon as possible. To stop splitting once it starts, grab the head and give it a one-half turn to break some of the roots. You also can

root prune

the plant by digging in a circle about 1 foot from the base of the cabbage. Both of these methods slow the uptake of water and fertilizer to preserve the head.

Cauliflower

When heads are between 6 and 12 inches in diameter and blanched white (for white varieties) or fully colored (for colored varieties), pull up the whole plant and cut off the head. Cauliflower, unlike cabbage and broccoli, won't form side heads after the main head is cut.

Chapter 10: A Salad for All Seasons: Lettuce, Spinach, Swiss Chard, and Specialty Greens

In This Chapter

Leafing through lettuce, spinach, and Swiss chard varieties

Leafing through lettuce, spinach, and Swiss chard varieties

Joining the green revolution: dandelions and other unusual greens

Joining the green revolution: dandelions and other unusual greens

Caring for your green crops

Caring for your green crops

If you're a beginning gardener and have never grown a vegetable in your life before, try greens. You'll find no easier group of vegetables to grow than greens. Unlike other vegetables that require weeks or even months of nurturing, greens are good things that come even to those who can't wait. Because you don't have to wait for flowering and fruiting to enjoy their green goodness, you can just pick the leaves at any stage, and — voilà! — you have dinner.

In many growing areas, you can have fresh greens year-round from your garden with just a little planning. Sure, it's easy to buy a head of lettuce at the grocery store or farmer's market, but the pure joy of running out to the garden in the evening and plucking a fresh head for dinner gives you a great sense of satisfaction while introducing you to unusual varieties and flavors not readily available from most supermarkets. Plus you don't have to push a shopping cart with a bad wheel or break up any arguments in the cereal aisle just to gather basic salad ingredients.

And speaking of salad, for most people, lettuce and salad are synonymous. Lettuce is definitely the number-one green, but in this chapter, I also discuss two other major greens crops: spinach and Swiss chard. In addition, I talk about my favorite unusual wild greens, including dandelions and sorrel. (Flip to Chapter 11 for details on other unusual yet more mainstream types of greens, such as arugula, collards, and endive.)

Greens, by nature, are cool, moisture-loving crops. When the weather heats up to above 80 degrees Fahrenheit for several days in a row and the plant is mature enough, annual greens such as lettuce and spinach think the end is near and send up a seed stalk. This process is called

Greens, by nature, are cool, moisture-loving crops. When the weather heats up to above 80 degrees Fahrenheit for several days in a row and the plant is mature enough, annual greens such as lettuce and spinach think the end is near and send up a seed stalk. This process is called

bolting.

Bolting doesn't just mean getting out of the house quickly. It's also a term used to describe a greens crop gone bad. During this process, the flavor of the greens quickly becomes bitter, so plan to plant and harvest your greens while the weather's cool or else grow varieties that are tolerant of the heat. I provide guidelines for growing all types of greens at the end of this chapter.

Lettuce Get Together

Originally from the Mediterranean area, lettuce (

Latuca sativa

) was eaten at the tables of Persian kings in 550 B.C. and was once thought to be an aphrodisiac. I can't attest to its aphrodisiacal qualities, but I do know that lettuce is considered the quintessential salad crop around the world.

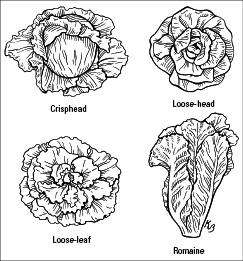

The four basic types of lettuce — crisphead, loose-head, loose-leaf, and romaine lettuce (all shown in Figure 10-1) — offer a number of tasty varieties to delight the palate. The most common are green-colored leaf varieties, but you can grow many red- and burgundy-colored leaf varieties and those with a mixture of colors, too. Some varieties form solid heads, but others don't. Varieties have smooth, frilly, or deeply cut leaves.

The following sections describe the four basic types of lettuce along with their days to maturity and some of my favorite varieties. They all are best in cool weather conditions, but some varieties can tolerate the heat. Just remember that lettuce can be eaten much younger, depending on your needs and appetite.

Crisphead lettuce

The crisphead group is most widely known as the "iceberg" lettuces, so named because when the lettuce was shipped from California (the main lettuce-growing region in the United States) to the East Coast in the early 1900s, mounds of ice were used to keep it cool and fresh.

The crisphead group is most widely known as the "iceberg" lettuces, so named because when the lettuce was shipped from California (the main lettuce-growing region in the United States) to the East Coast in the early 1900s, mounds of ice were used to keep it cool and fresh.

Figure 10-1:

Crisphead, loose-head, loose-leaf, and romaine lettuce all have distinct shapes.

‘Iceberg' is the most widely known variety, but many other crispheads are just as tasty and easy to grow. This type of lettuce forms a solid head when mature, with white, crunchy, densely packed inner leaves. Crispheads tend to take at least 70 days to mature from seeding in the garden. Following are some popular varieties of crisphead lettuce:

‘Iceberg':

‘Iceberg':

Famous in grocery stores across the country, these compact heads have tightly-packed smooth leaves and white hearts. They're best when grown in cool conditions (below 70 degrees), because then they form solid heads. (Find tips for growing head lettuce in the section "Growing Great Greens," later in this chapter.)

‘Nevada':

‘Nevada':

This French crisphead features upright, bright green ruffled leaves with a nutty flavor. These cool-weather plants resist tip burn, rot, and bolting.

‘Summertime':

‘Summertime':

So named for its ability to form solid heads in the heat of summer, ‘Summertime' has green, frilly leaves and a crisp texture.

Romaine lettuce

Romaine was named by the Romans, who believed in the healthful properties of this type of lettuce. Emperor Caesar Augustus even built a statue in praise of romaine lettuce, so it's no surprise that this is the type of lettuce featured in Caesar salad. The alternative name, "Cos," comes from the Greek island of Kos, where it's popular.

Romaine was named by the Romans, who believed in the healthful properties of this type of lettuce. Emperor Caesar Augustus even built a statue in praise of romaine lettuce, so it's no surprise that this is the type of lettuce featured in Caesar salad. The alternative name, "Cos," comes from the Greek island of Kos, where it's popular.