Vegetable Gardening (13 page)

How are you to know whether your growing season is long enough? If you check mail-order seed catalogs or even individual seed packets, each variety will have the number of days to harvest or days to maturity (usually posted in parentheses next to the variety name). This number tells you how many days it takes for that vegetable to grow from seed (or transplant) to harvest. If your growing season is only 100 days long and you want to grow a melon or other warm-season vegetable that takes 120 frost-free days to mature, you have a problem. The plant will probably be killed by frost before the fruit is mature. In areas with short growing seasons, it's usually best to go with early ripening varieties (which have the shortest number of days to harvest).

However, you also can find many effective ways to extend your growing season, such as starting seeds indoors or planting under

However, you also can find many effective ways to extend your growing season, such as starting seeds indoors or planting under

floating row covers

(blanketlike materials that drape over plants, creating warm, greenhouselike conditions underneath). Various methods of extending growing seasons are covered in Chapter 21.

There you have it; now you know why frost dates are so important. But how do you find out dates for your area? Easy. Ask a local nursery worker or contact your local Cooperative Extension office (look in the phone book under

county government

). You also can look in the appendix of this book, which lists frost dates for major cities around the country.

Frost dates are important, but you also have to take them with a grain of salt. After all, these dates are averages, meaning that half the time the frost will actually come earlier than the average date and half the time it will occur later. You also should know that frost dates are usually given for large areas, such as your city or county. If you live in a cold spot in the bottom of a valley, frosts may come days earlier in fall and days later in spring. Similarly, if you live in a warm spot or you garden in a microclimate, your frost may come later in fall and stop earlier in spring. You're sure to find out all about your area as you become a more seasoned vegetable gardener and unearth the nuances of your own yard. One thing you'll discover for sure is that you can't predict the weather.

Frost dates are important, but you also have to take them with a grain of salt. After all, these dates are averages, meaning that half the time the frost will actually come earlier than the average date and half the time it will occur later. You also should know that frost dates are usually given for large areas, such as your city or county. If you live in a cold spot in the bottom of a valley, frosts may come days earlier in fall and days later in spring. Similarly, if you live in a warm spot or you garden in a microclimate, your frost may come later in fall and stop earlier in spring. You're sure to find out all about your area as you become a more seasoned vegetable gardener and unearth the nuances of your own yard. One thing you'll discover for sure is that you can't predict the weather.

Listening to your evening weather forecast is one of the best ways to find out whether frosts are expected in your area. But you also can do a little predicting yourself by going outside late in the evening and checking conditions. If the fall or early spring sky is clear and full of stars, and the wind is still, conditions are right for a frost. If you need to protect plants, do so at that time. Frost-protection techniques are covered in Chapter 21.

Designing Your Garden

After you've found the best spot for your plot, selected a few veggie varieties, and figured out when you need to plant those varieties, it's time to map out your garden. Designing a vegetable garden is a little bit of art and a little bit of science. Practically speaking, plants must be spaced properly so they have room to grow and arranged so taller vegetables don't shade lower-growing types. Different planting techniques fit the growth habits of different kinds of vegetables. You also should think about the paths between rows and plants. Will you have enough room to harvest, weed, and water, for example?

On the other hand, having fun with your vegetable garden design is important too. Many vegetables are good looking on their own, but you also can get creative with combinations of vegetables with different flowers and herbs.

In the following sections, I give you the basics so you can start to sketch out a garden plan. I also provide some sample designs to get your juices flowing. If you stick with your plan, you'll be a vegetable gardening wizard in no time.

These sections give you the nuts and bolts information you need to create a final vegetable garden design. Don't stop here though. The descriptions of individual vegetables in Part II suggest ways to grow various types of vegetables — information that will probably influence your design. And the information on planting times earlier in this chapter, the scoop on succession planting in Chapter 16, and the lowdown on watering techniques in Chapter 15 can influence the way you arrange and plant your garden.

These sections give you the nuts and bolts information you need to create a final vegetable garden design. Don't stop here though. The descriptions of individual vegetables in Part II suggest ways to grow various types of vegetables — information that will probably influence your design. And the information on planting times earlier in this chapter, the scoop on succession planting in Chapter 16, and the lowdown on watering techniques in Chapter 15 can influence the way you arrange and plant your garden.

Deciding on hills, rows, or raised beds

Before you sketch a plan, you need to decide how to arrange the plants in your garden. You can use three basic planting arrangements:

In rows:

In rows:

Planting vegetables in rows is the typical farmer technique.

Any vegetable can be planted in straight rows, but this arrangement works best with types that need quite a bit of room, such as tomatoes, beans, cabbages, corn, potatoes, peppers, and summer squash.

In hills:

In hills:

Hills are typically used for vining crops such as cucumbers, melons, pumpkins, and winter squash. You can create a 1-foot-wide, flat-topped mound for heavy soil, or you can create a circle at ground level for sandy soil. You then surround the soil with a moatlike ring for watering. Two or three evenly spaced plants are grown on each hill. Space your hills the recommended distance used for rows of that vegetable.

In raised beds:

In raised beds:

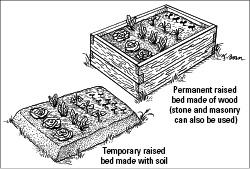

Raised beds, which are my favorite, are kind of like wide, flat-topped rows. They're usually at least 2 feet wide and raised at least 6 inches high, but any planting area that's raised above the surrounding ground level is a raised bed. Almost any vegetable can benefit from being grown on a raised bed, but smaller vegetables and root crops, such as lettuce, beets, carrots, onions, spinach, and radishes, really thrive with this type planting. On top of the raised bed you can grow plants in rows or with broadcast seeding (see Chapter 13 for more on seeding techniques).

A raised bed can be a normal bed with the soil piled 5 or 6 inches high. I call this a

temporary raised bed.

Or you can build a

permanent raised bed

with wood, stone, or masonry sides, as shown in Figure 3-2.

Figure 3-2:

Raised beds can be made with soil alone, or with wood, stone, or masonry sides.

Raised beds have several advantages, including the following:

They rise above soil problems.

They rise above soil problems.

If you have bad soil or poor drainage, raised beds are for you. You can amend the garden soil in the raised bed with compost or the same sterile potting soil you use for containers (see Chapter 18). And because you don't step on the beds as you work, the soil is more likely to stay light and fluffy, providing the perfect conditions for root growth — especially for root crops such as carrots and beets.