Vegetable Gardening (129 page)

Here are a couple ways to check whether your container is dry:

•

Stick your finger in the soil.

If the top few inches are bone dry, you should water.

•

Lift or tip the container on its side.

If the soil is dry, the container will be very light.

Water more thoroughly.

Water more thoroughly.

Wetting dry potting soil can be tricky. Sometimes, the root ball of the plant (or plants) shrinks a bit and pulls away from the side of the pot as the soil dries so that when you water, all the water rushes down the space on the side of the pot without wetting the soil. To overcome this problem, make sure you fill the top of the pot with water more than once so the root ball can absorb the water and expand. In fact, you should always water this way to make sure the root ball is thoroughly wet. It's also important, however, to avoid overwatering the soil; do the finger check before watering.

If you still have problems wetting the root ball, place your pot in a saucer and fill the saucer repeatedly with water. The water soaks up into the root ball and slowly wets all the soil.

If you have a lot of pots, you may want to hook a drip irrigation system to an automatic timer to water them; nurseries and garden centers sell special drip emitters designed for pots. You can find out more about drip irrigation and emitters in Chapter 15.

If you have a lot of pots, you may want to hook a drip irrigation system to an automatic timer to water them; nurseries and garden centers sell special drip emitters designed for pots. You can find out more about drip irrigation and emitters in Chapter 15.

Fertilize more frequently.

Fertilize more frequently.

Because nutrients are leached from the soil when you frequently water container vegetables, you need to fertilize your plants more often — at least every 2 weeks. Liquid or water-soluble fertilizers (you just add them to water) are easiest to use and get nutrients down to the roots of your plants. A complete organic fertilizer is best. (See Chapter 15 for more detailed fertilizer info.)

Watch for pests.

Watch for pests.

Worried about insects and diseases harming your container plants? Don't be too concerned. In general, vegetables in containers have fewer pest problems because they're isolated from other plants. Insects aren't waiting on nearby weeds to jump on your plants, and sterilized potting soil (which I recommend for container gardening) doesn't have any disease spores.

Even though container vegetables tend to have fewer pest problems, you should quickly deal with any problems that arise so your whole crop isn't wiped out. Solve your pest problems by using the same techniques that you use in your garden. Check out Chapter 17 to read about controls for specific diseases and insects.

Because container vegetables are often located on patios or decks that are close to the house, special care should be used in spraying them for pests. I know I said container vegetables don't get as many pests as in the garden, but you may have to spray occasionally; so, if possible, move the containers away from the doors and windows when you spray.

Because container vegetables are often located on patios or decks that are close to the house, special care should be used in spraying them for pests. I know I said container vegetables don't get as many pests as in the garden, but you may have to spray occasionally; so, if possible, move the containers away from the doors and windows when you spray.

Experimenting with Greenhouses, Hoop Houses, and Hydroponics

You can grow cucumbers, tomatoes, and other vegetables in the dead of winter in a

greenhouse

(an enclosed, heated, controlled-atmosphere room). In fact, farmers throughout the world do it all the time. You don't even have to have a glass structure for a greenhouse. You can use plastic hoop houses instead. They're easy to build, inexpensive, and a great way to extend the growing season. (See Chapter 21 for more on hoop houses.) Either way, greenhouse growing is more involved — it's container gardening and vegetable growing at their highest levels; everything has to be just right to get a good crop. But maybe I've helped turn you into a really good gardener, so everything will be just right. After all, that was the point of this book.

You need to pay attention to many more conditions in a greenhouse, such as temperatures that are too hot and too cool, fertility, pests (once they get started, they're tough to stop in a greenhouse), pollination for crops like cucumbers and melons, and so on. You generally have to be more dedicated to vegetable gardening to grow good crops in a greenhouse. The easiest time to grow them is in the spring and fall to extend the season. Winter and summer are the toughest times to grow plants in a greenhouse because of the extremes in temperature and available light.

You need to pay attention to many more conditions in a greenhouse, such as temperatures that are too hot and too cool, fertility, pests (once they get started, they're tough to stop in a greenhouse), pollination for crops like cucumbers and melons, and so on. You generally have to be more dedicated to vegetable gardening to grow good crops in a greenhouse. The easiest time to grow them is in the spring and fall to extend the season. Winter and summer are the toughest times to grow plants in a greenhouse because of the extremes in temperature and available light.

Another term that's associated with container vegetables is

hydroponics

(see the appendix for companies specializing in hydroponics). You may have bought hydroponic tomatoes at the grocery store, or you may have seen the amazing hydroponic lettuce at Disney World. When you grow hydroponic vegetables, you grow the plants in a soilless, liquid solution that provides all the plant's nutrient needs. You need special equipment and growing techniques, but you can grow any plant this way.

For more information on growing plants in greenhouses and hoop houses, visit

growinggreenhouse.com

. If you want to read more about growing plants hydroponically, check out

www.hydroponics-at-home.com

.

Chapter 19: Harvesting, Storing, and Preserving Vegetables

In This Chapter

Harvesting your vegetables at the right times

Harvesting your vegetables at the right times

Storing your crops

Storing your crops

Preserving your crops by freezing, drying, or canning

Preserving your crops by freezing, drying, or canning

Saving seeds from your vegetables

Saving seeds from your vegetables

Suppose that you've done everything you need to do in your garden: You planted your veggies at the right time, watered and fertilized them as needed, and kept an eye out for pests. Way to go. Now for the best part: It's time to eat!

To get all the best flavor and highest nutritional value from your vegetables, you need to pick them at just the right time. Some vegetables taste terrible if you pick them too early; others are tough and stringy if you pick them too late.

And after you pick your vegetables, what if you can't eat them right away? When properly stored, most vegetables last a while without rotting or losing too much flavor (of course, eating them fresh picked is always best). In fact, you can store some vegetables, like potatoes and winter squash, for months.

So in this chapter, I discuss harvesting and storing your fresh vegetables. You put in too much work not to do the final steps just right.

Knowing When to Harvest

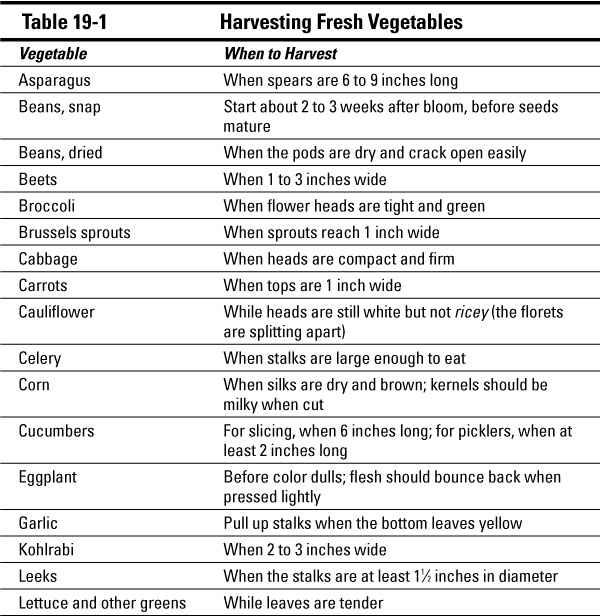

You should harvest most vegetables when they're young and tender, which often means harvesting the plants, roots, or fruits before they reach full size. A 15-inch zucchini is impressive, but it tastes better at 6 to 8 inches. Similarly, carrots and beets get

woody

(tough textured) and bland the longer they stay in the ground. Table 19-1 provides specific information on when to harvest a variety of veggies.

Other plants are continuously harvested to keep them productive. If you keep harvesting vegetables like snap beans, summer squash, snow and snap peas, broccoli, okra, spinach, and lettuce, they'll continue to produce pods, shoots, or leaves.

A good rule for many of your early crops is to start harvesting when you have enough of a vegetable for a one-meal serving. Spinach, Swiss chard, scallions, radishes, lettuce, and members of the cabbage family certainly fit the bill here. These veggies don't grow as well in warm weather, so pick these crops in the spring when temperatures are cooler.

A good rule for many of your early crops is to start harvesting when you have enough of a vegetable for a one-meal serving. Spinach, Swiss chard, scallions, radishes, lettuce, and members of the cabbage family certainly fit the bill here. These veggies don't grow as well in warm weather, so pick these crops in the spring when temperatures are cooler.

After you start harvesting, visit your garden and pick something daily. Take along a good sharp knife and a few containers to hold your produce, such as paper bags, buckets, or baskets. Wire or wood buckets work well because you can easily wash vegetables in them.

The harvesting information in Table 19-1 is based on picking mature or slightly immature vegetables. But many vegetables can be picked smaller and still have excellent flavor. Pick baby vegetables whenever they reach the size that you want. The following vegetables can be picked small: beets, broccoli, carrots, cauliflower, cucumbers, lettuce and other greens, onions, peas, potatoes, radishes, snap beans, summer squash, Swiss chard, and turnips. In addition, some small varieties of corn and tomatoes fit the baby-vegetable mold.

The harvesting information in Table 19-1 is based on picking mature or slightly immature vegetables. But many vegetables can be picked smaller and still have excellent flavor. Pick baby vegetables whenever they reach the size that you want. The following vegetables can be picked small: beets, broccoli, carrots, cauliflower, cucumbers, lettuce and other greens, onions, peas, potatoes, radishes, snap beans, summer squash, Swiss chard, and turnips. In addition, some small varieties of corn and tomatoes fit the baby-vegetable mold.

Be sure to avoid harvesting at the following times:

Be sure to avoid harvesting at the following times:

When plants, especially beans, are wet.

When plants, especially beans, are wet.

Many fungal diseases spread in moist conditions, and if you brush your tools or pant legs against diseased plants, you can transfer disease organisms to other plants down the row.

In the heat of the day, because the vegetable's texture may be limp.

In the heat of the day, because the vegetable's texture may be limp.

For the freshest produce, harvest early in the day when vegetables' moisture levels inside the vegetables are highest and the vegetables are at peak flavor. After harvesting, refrigerate the produce and prepare it later in the day.