Valley of the Shadow: A Novel (41 page)

Read Valley of the Shadow: A Novel Online

Authors: Ralph Peters

In the Good Book, dreams were either visions or warnings. What did

his

mean? Were they sent by the Lord, or by Satan?

He would have liked to talk to Elder Woodfin but was ashamed. A true man wasn’t scared of things like nightmares. All he could do was to pray for the dreams to stop.

Lying awake on pebbled ground, on a blanket worn thin as muslin, he held his eyes open, watching the stars, on guard for his mortal soul.

What if a man shut his eyes and never returned? What if he couldn’t wake up, couldn’t escape? What if death—a sinner’s death—left him eternally captive to his dreams? Nichols shuddered. The prospect seemed far worse than devils with pitchforks.

Someday, he promised himself, all this would end. He would go home and marry a woman as faithful and good as Ruth, and she would comfort him. He would close his mind against these things forever.

“Dear Jesus,” he begged, “don’t let none of my friends know I’m so afraid.”

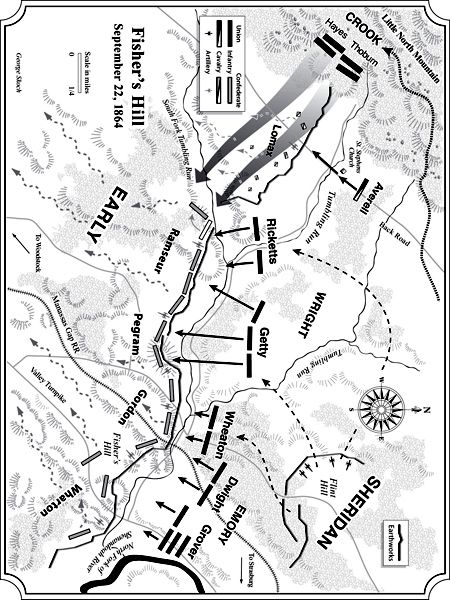

September 22, 3:00 p.m.

Ricketts’ division

Where was Crook? Ricketts had been swapping artillery rounds with the Rebs since morning and prodding them with his infantry, just hard enough to imply he might be serious. It hadn’t been much of a fight, more a Punch and Judy show, though with real blood. And that was the problem: It irked him to squander men, even a few, on “demonstrations.” Taking Flint Hill the day before had made good tactical sense, but this skirmishing struck him as frivolous.

By nature, he was given to doing things properly. Or not doing them. He understood the rationale for his orders, this need to keep the Johnnies mesmerized. Yet he felt he was frittering men away. The textbooks called such actions “amusing the enemy,” but Jim Ricketts didn’t find them entertaining.

The men were surprisingly game, though, whether playing cat and mouse with Confederate skirmishers or waging artillery duels. For all the losses at Winchester, victory had inspirited his soldiers, opening new and promising possibilities, awakening bloodlust.

Up on the heights, the enemy lines bristled. Immobile. Confident.

Where was Crook?

Ricketts knew his men were running down. These mortal games made weary children of all. He wanted his division to remain strong enough to be in on the kill; his men had earned that.

Earned?

He smiled at himself. Thinking of the evident jealousies newly abroad in the army, resentments he once would have wallowed in himself. The past five months, the carnage, had taught him much—to the extent that a man learned anything of worth, which was a separate issue. It just didn’t pay to envy another’s fame, deserved or not: He had learned that painfully. You couldn’t give in to jealousy, or you poisoned yourself. And war was poison enough.

Of course, praise made him preen, as it did any man, but the approbation he wanted waited at home. He needed the respect of his wife, Frances, a woman of immense courage and selflessness. And he longed for the blessing of Harriet, the dead wife who haunted him still. Had he ever praised either one of them enough? His vanity, he saw, had been colossal. War was a mirror that rarely flattered a man.

After Monocacy,

he

had been praised and Wallace, the effort’s architect, consigned to oblivion. Or to Baltimore, which was as bad. At Winchester, though, it had been young Upton’s turn to gather laurels, with the sacrifices of Ricketts’ division ignored. Wright had been the savior of Washington. But Crook eclipsed him easily at Winchester. Thus was glory allotted, almost as random as cards dealt in a poker game.

Glory? Oh, he remembered that seductress, the murderous slut. Hadn’t the loins for her now. He was just a graying, begrimed man in a bitter war, hoping to do his duty and evade shame.

Where the hell was Crook?

Hot and thirsty, all but irate, and sore from too many hours in the saddle, Ricketts smiled. Had the fates already pivoted against Crook? Had his movement along the side of the mountain failed? The wheel of fortune turned, and a man had to be content not to be crushed.

Where the devil

was

the fellow, though? Good men were dying.

Thanks to the intervening ridges and smoke, he couldn’t see much of the mountainside where Crook’s men were supposed to be sneaking along. All he could do was to wait. And continue sending men forward only to see fewer men return.

When Wright explained the plan to his subordinates, Ricketts had shared the general skepticism, but he certainly wanted Crook’s fool trick to work. He feared the collapse of the flanking attempt would precipitate an order to launch a frontal attack. And his men had endured enough mindless assaults.

Spotsylvania.

Good God. How much glory had its mud produced?

Up on the heights, Reb officers pranced on their horses, appearing to pay social calls. No soldierly eye would judge them much concerned.

Where was Crook?

Ricketts rode forward, through wisps of smoke, to order Keifer to bring up another regiment. To “amuse” the Johnnies. While waiting for deliverance.

3:15 p.m.

Early’s headquarters

“I don’t like it,” Early muttered. “I don’t like this at all.”

“Want me to draft the order, sir?” Sandie Pendleton asked.

“Write it up, write it up. Army’s to withdraw, right after dark. Meantime, call up the wagons, just do it quiet. Come morning, I don’t want that low-down cur to sniff one Confederate backside on this hill.” Early drew a twist of tobacco from his pocket and bit off a chaw. “I’ll see Sheridan in Hell, before this is over. Just not here, not here.”

Early was correct, as far as tactics went. Pendleton saw that now. The position was fine, but the men were too thin on the ground and they had no reserve. Everyone had engaged in wishful thinking, declaring Fisher’s Hill to be impregnable, desperate to believe it after Winchester. Defeat could be intoxicating, too, in a dreadful way, but as men sobered up they saw their weakness: The army lacked the numbers to hold this ground, if Sheridan applied brute force again. It was time to slip away before they were trapped, and Early was showing the fortitude to do the sensible thing, knowing the Richmond papers and even his own subordinates would condemn him. The Old Man was showing courage of a rare kind and could expect no thanks from any quarter.

Still, Pendleton feared for the army’s morale if they retreated again without a fight.

He said nothing of that to Early. There simply were no good choices, and the Old Man had faced contention enough of late. His generals carped and quarreled, dissecting past events, when they needed to look the future in the eye. And Early sat up by a lantern’s light, alone in his tent and muttering, until dawn.

Spitting amber juice, the general snapped, “I know what Sheridan’s up to, I’m no fool. He’s looking for the weak spot in our line. Planning to hit us first thing in the morning, come first light. Before we can be reinforced. Well, let him waste his powder, we’ll be gone.” He wiped wet from his beard. “Get that order in everybody’s hands by five p.m. And no excuses.”

“Yes, sir,” Pendleton said. He never did make excuses, except for Early’s behavior, but he knew not to take offense.

To the north, the

pock-pock

of skirmishing passed the time between battery squabbles. Despite the firing, it hadn’t been much of a day. The Yankees seemed tuckered out, too, although it might well be that Early was right, that Sheridan was feeling their line and meant to attack in the morning. And another whipping like Winchester, Pendleton had to admit, would be a sight worse for morale than just marching off.

He dipped his best steel pen and began to write.

3:50 p.m.

Ramseur’s position, left flank of Fisher’s Hill

Stephen Dodson Ramseur had a headache. He sought shade when he could, only to feel guilty about leaving his soldiers out in their sun-punched trenches. Even the letter from his wife annoyed him. It was one of her playful “Dearest Doddie” missives, the kind he usually cherished, full of gossip, household details, and promises that the child would arrive in October. Today, the curls of her penmanship made his head pound.

With the letter in his pocket, he walked the line again, watching the Yankees across the little valley. They swarmed like bees without the heart to sting. His enemies had suffered, too. He had made them suffer. He didn’t believe they were eager to bleed again.

The only thing that worried him was their numbers. Only way they’d won that fight: sheer numbers. Yanks hadn’t shown a lick of skill at Winchester, not one hint of tactical finesse.

Clouds off to the west, past Little North Mountain. Rain in the night, Ramseur figured. Trenches would get muddy as pigpens in May. Nothing to be done about it.

He had to stop, to stand stone still, and close his eyes against the throb in his head. Lord, the hordes of Yankees back at Winchester, those endless ranks of blue …

Winchester.

He had expected praise from Jubal Early. His men had been the first to fight in the morning and the last to leave the battlefield at night. But all Early offered anyone was abuse. Ramseur recalled, with a rueful smile, how he once had hoped to be Early’s favored subordinate. Early didn’t like anyone.

Warm day. Not hot, but bright, painfully bright. The clouds to the west moved so slowly, they seemed to hold still. Could have used their shade that very minute. Head hurting like he’d been kicked by Jenkins’ mule.

Trailed by new aides in place of those lost at Winchester, Ramseur strode toward the emplacements of the Fluvanna Artillery.

Bryan Grimes intercepted him. The brigadier was limping—almost hopping—and clearly agitated.

“General Ramseur?”

“How may I serve you, Bryan?”

“Sir, we have to send a brigade, at least a brigade, down to Lomax. Cavalry won’t hold, not without support. There’s Yankees all over the mountain, they’ll turn his flank.”

What on earth?

Almost unwillingly, Ramseur turned to face Little North Mountain, shielding his eyes.

“What are you talking about?”

Grimes pointed. “That bald spot. Halfway up, or thereabouts. See that file of Yankees?”

Ramseur peered at the mountainside. “Only thing I see looks like a fence row. I don’t see anything moving.”

“Call for your field glasses, sir. There’s Yankees up there. On my honor, one Tar Heel to another. They’re going to come down behind Lomax, way they’re moving.”

Ramseur just wanted to close his eyes, but he forced an indulgent smile. He didn’t want to get off to a bad start with a new subordinate. “Well, if you’re right, it’s probably just a scouting party. Even the Yankees aren’t fools enough to attack that way, they’d fall to pieces.”

Grimes opened his mouth to reply but seemed to think better of it.

“What’s that limp of yours about?” Ramseur asked to soothe things.

The brigadier shrugged. “Damned-fool thing. Just plain walking along, not even running. And I gave my ankle a twist, craziest thing.”

“Well, go sit down, rest up. You’re apt to be needed over the next few days.”

Grimes saluted, crestfallen. “Keep watch on that mountain, sir. I’d be beholden.”

Alone again—but for his anxious aides—Ramseur continued on to the gun positions. He valued artillery and liked to display his knowledge. But as he walked in front of a piece drawn back for a repair, a sergeant said, “General, there’s blue-bellies on that mountain yonder, a right bushel.”

Ramseur took a breath to stay his temper.

“I know what’s caught your eye. It’s just a fence row.”

“Well, sir, that there’s a

moving

fence row, if it’s a fence at all.” The man’s tone was all but insolent. Had Rodes allowed such back talk? Or was it yet another mark of defeat? Ramseur shook his head, just to himself, and it felt as though his brains banged around in his skull. Everybody had the jumps. And the cannoneers around him plainly put more stock in their comrade’s words than in their general’s.

Only one way to settle this, Ramseur decided. He turned to his nearest aide.

“Go back and fetch my field glasses.”

But the battery commander had come up. He drew his own binoculars from their case. “Here. Use mine, sir.”

With an outright sigh, Ramseur took the glasses, tilted up the front brim of his hat, and began to scan the mountain a mile or so off.

He saw nothing but jutting gray rocks. Trees. Green tresses and tangles.

Then he stopped and held the glasses steady.

“My God.”

3:50 p.m.

Little North Mountain

Rud Hayes grabbed a branch in time to stop himself from tumbling down the mountainside.

“Careful, Rud,” Crook told him. Crook was grinning, despite the day’s exertions. “I need you to help me out of this fix I’m in.”

But they weren’t in a fix, at least not yet. The movement up the side of the mountain and then along its flank had required sweat and muscle-burning effort, as well as costing any number of busted ankles and one broken leg, but the men, coming along in Indian files, had suspended their common complaints, with every veteran grasping what they were doing and what it might mean. Quiet curses erupted now and then as men lost their footing or banged a knee, but the corps as a whole moved in remarkable quiet, eager and murderous.