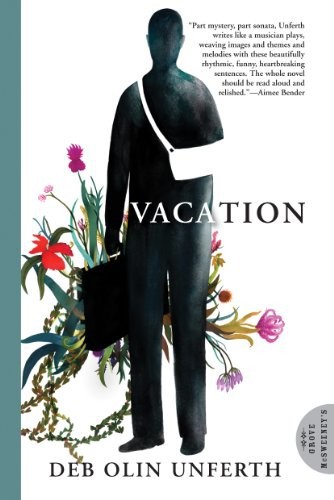

Vacation

“In this enthralling headscratcher of a first novel, Unferth weaves an intricate tale of quests and escapes, of leaving and following.” —

Publishers Weekly

“Deb Olin Unferth is, I believe, one of the crucial literary artists of her generation. Her vision evokes high comedy and the violence of tragedy heard through voices exquisitely particular to her mind.”

—Diane Williams, author of

It Was Like My Trying to Have a Tender-Hearted Nature

“Unferth is always playing a sort of life-or-death word game. She will seize a word and wring all meanings from it, like a terrier worrying a bone . . . in their very abstraction the descriptions can be truly poignant.”

—Madison Smartt Bell,

The

New York Times Book Review

“Told in a lean voice that feels completely new, you’ll be pleased to discover that it’s all quite funny, too.”

—Chris Ware, author of

Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth

“Sentence by sentence, Unferth surprises and makes profound sense of what it is to be alive. Loud applause should follow this accomplished—entertaining, funny, sad, solemn—book.” —Christine Schutt, author of

Florida

“For most people, traveling is supposed to be a time of personal rejuvenation and general R&R—a period when you shouldn’t have to do anything more strenuous than order a frozen margarita. Deb Olin Unferth’s inventive debut novel,

Vacation,

turns that idea on its head. Her characters might visit foreign beaches and linger in Internet cafes, but they are primarily careening into existential crisis . . . her book excels at exploring the remote reaches of her characters’ psyches.”

—

Time Out New York

“Unferth’s sentences are dazzling . . . But

Vacation’

s trickiest trick is cartwheeling along the border between the simplicity of allegory and the complexity of true human frailty. Makes you love these characters, too.” —

Philadelphia City Paper

“[

Vacation

] showcases Unferth’s unbridled gift for inspired narrative wordplay.”

—

Elle

“The quirky, metafictional gloom is part of the charm of this novel and is a critical gear in the apparatus that propels it to its lonely conclusion in a far-flung corner of the earth.” —

Bookforum

“

Vacation

is fantastic . . . Funny, bleak, often brilliant,

Vacation

once again proves that Unferth can perform a linguistic high-wire act all her own.” —

Esquire

“

Vacation,

Deb Olin Unferth’s dreamy, surreal debut novel, reads like an extended hallucination or out-of-body experience, as unsettling as it is compelling.”

—

The

Village Voice

“Unferth skillfully layers what for another writer might be throwaway details into a gripping psychological adventure, and the persistence of her writing turns a rather abstract work . . . from a postmodern anti-narrative into prose that grips the reader like a Jane Austen novel.” —

Review of Contemporary Fiction

“Fans of Dave Eggers’s ever estimable literary concern McSweeney’s are finally catching onto what fans of Diane Williams’s unsung journal

NOON

have been savoring for years: the tidy, tuneful uncertainties that weave to form the fictions of Deb Olin Unferth.”

—Boston Phoenix

“The genius of this sad, poignant, and hilarious book is its capacity to demonstrate how hollow our destinations can be, while simultaneously showing how much fun can be had in the going.” —

American Book Review

“A lyrical web of vignettes, letters, e-mails and confessions told from multiple points of view,

Vacation

threads the themes of loss, travel, escape, revenge, abandonment, disillusionment, fathers, daughters and betrayal.” —

Richmond Style Weekly

“A

t the heart of Deb Olin Unferth’s astonishing, unsettling first novel is the idea and intention of vacation: What do we escape from? Where do we go?”

—

Rain Taxi

“Unferth is a hero . . . She has shown up early to the party with a book’s worth of undeniably unique prose. All there is left to do is to sit back and wait for the imitators.” —

Splice Today

“

Vacation

is a remarkable and ambitious must-read, and Unferth herself an exciting writer to keep watch on. Without a doubt, there are more great things still to come.” —

New Pages

“It is a formidable task to produce work that asks ‘the big questions’ in a way that does justice to the enormity of those questions . . . Unferth’s imaginative, fractured, uncompromising

Vacation

is urgently contemporary without failing to strike at the heart of the most enduring human concerns.” —

Rumpus

Vacation

Vacation

deb olin unferth

McSWEENEY’S

Grove Press

Copyright © 2008, 2010 by Deb Olin Unferth

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003 or [email protected].

First published in 2008 by McSweeney’s Books, San Francisco

Printed in the United States of America

Published simultaneously in Canada

ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-4472-0

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

10 11 12 13 14 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In memory of John Kenneth Unferth (1965–2004)

Chapter One

CLAIRE

I recall only one sentence that she said. She said it all the time. Every day was an occasion. If she had to be away on a shoot, she said it to my father. If I had to take cough syrup, she said it to me. She said it to the family dog before his operation. It was her wisdom. She said it with pride. What my mother said was: You won’t even feel it.

I was born in the city. My father was a bank man, my mother starred in soaps. We lived like the famous in a house by the park and I woke to a vase of fresh tulips each day. We had long hallways and long tablecloths. My mother had rooms full of clothes. So many strangers gave us presents that we had a man to pen our thank-yous. Photographers slept outside the house.

One day when I was five, my mother was hit by a car and she felt it and she died and we felt it. We went away for a while, paid off our debts from afar, tried to live without her. We came back to the city. My father’s business spoiled dollar by dollar. We lived on her money. Each year we grew poorer. We sold the house and moved into a smaller house and then into a large rented apartment, then into a smaller one. We moved around the city, fitting into smaller and smaller spaces, each time carrying our valuables up and down stairways—the chests, the paintings, the family china, the sofas, the wardrobes. We finally landed in the smallest studio with the dog and our little cat and all of our furniture and light fixtures and jewelry. We laid out the expensive rugs one on top of another on the floor. We hung the paintings floor to low ceiling. It was in this room that my father became sick and couldn’t work. We sold our things off one by one, peeled up a rug or took down a picture, and in this way we paid the medical bills and the other bills and we lived, somewhat. When the floor and walls were bare and the room was mostly cleared out, my father had one more thing to tell me. Early in our marriage, he said, your mother ran off with someone else and she came back pregnant. You are not my daughter.

I felt that too.

I was sixteen that year.

Today I thought about the man who raised me because of a man who sat down next to me on the train. He had a strangely shaped head. It seemed to be almost dented a little. He kept to himself on his seat and

I to myself on my seat. We regarded one another.

Later I woke to an empty seat beside me and we pulled into the Syracuse depot. I looked out the window at the few frail people waiting for a train the other way, a strip of woman and her tiny, mittened girl. Suitcases on the bench. And there, I saw him, the man with the head.

He’d gotten off the train. He was standing flush-faced in the chill, his suitcase on the platform, his hat crushed in his hand like a wad of paper, the other hand curled around the handle of a briefcase. A businessman. A man with a two-week vacation that he gets no matter what. If he dies and hasn’t used his two weeks, they wrench open his coffin and put the money inside.

But who would want to waste a vacation on a place like that, a town so cold and so small, jammed into the countryside like a sliver? Part of a train ticket, an extra included in the fare, is that they’ll move you even if you don’t know where you are or how to get anywhere. If you are too exhausted or brainless, if your brain has been killed off and destroyed, if you are dead, they will still transport you, as long as your ticket has not expired. That’s how that man looked at that moment with the splinter of Syracuse stuck in his head. He looked a little like the man I had called father most of my life—not the head, my father’s was a perfect egg, but because he had the same false energy of someone who does not yet know they are down for the count. Then the train was pulling out. He followed it, first with his eyes, then with his body, turning as it went.

I closed my eyes. I didn’t want to see him left behind.

Chapter Two

The train pulled away. Myers walked the length of the platform.

He took a cab to Gray’s neighborhood, lines of identical houses in rows, different from each other only in superficial ways—the size of the chimney or placement of the porch—or in meeker assertions, a mailbox that looked like a reindeer, a soggy doll fastened to a swing. Evidence of thoughtless, pleasureless lives.

The taxi pulled up to Gray’s house. It was set back from the street and it sunk into the coming darkness. Shut blinds, an empty driveway, an unmowed lawn. The cabman put the car in park, swiped the meter. Myers stayed where he was.

They don’t just spill onto the sidewalk, my friend, the cabman said. You go up and ring the bell. Ding dong.

Myers got out and ran up. It was raining here too and water went down his face. He rang and waited. No one came to the door. He flipped the mailbox. A full run of mail, side-stacked, stuffed. He rang again. He opened the screen and knocked. An ineffectual thud on solid wood. The house was the muted color of a people dominated by the landscape, people who just want to get something down that won’t blow away. He knocked again, rapped on the diamond window. Through it, dark shapes, stillness.

So Gray wasn’t home yet. Okay. He grasped the doorknob, turned it (why not? the fucker), shook it. It was locked. He looked at his watch. Now what.

Under his feet the word welcome had its say.

He ran back to the taxi.

Where’d you come in from? asked the cabman, turning the meter back on, putting the car in park. Myers told him (wearily) and the cabman said he’d been there, damn fine locale, a bit busy, you know what, they put their garbage on the sidewalks and there’s traffic, crime, parking’s impossible, but nice spot. Then the cabman told him where he, the cabman, was from and also told him where his parents were from and where their parents were from and his wife’s parents too, both sides and the sides before that. Then he went on to tell him about his daughter—age, eye color, favorite book this week, favorite book last week—then about his wife and the wife before this one, which one was better, in what ways. Then about the circles he drove in each day and what changes he noticed in them, in the cement and the paint and the people, the spread of Syracuse, the flat of it, all this and more, and how long did Myers want to wait?

Hi Gray, he was going to say. Thought I’d just drop in, see what you had going on here. Check in on the nearby alumni, sort of knock around. I see the kitchen could use a coat of paint. Maybe some new cabinets. Somebody should take apart that foosball table. How about if I give you a hand? Whatever’s needed, whatever minor chore stands undone. Here, why don’t you get up on this ladder, Gray, check the gutter—careful! Oh, oops. Hand me that hammer, would you? That saw? That power drill? Lean over this way a little. I can’t seem to get your eye from this angle.

Small satisfactions awaited him on the other side of these moments.

Was Gray a fix-it man? Did he own a foosball table? A ladder?

When Myers thought about it, he didn’t know anything about the guy.

Outside, twig trees, half-empty, dim in last daylight, the day moving to night. A scratch of naked bushes. Inside, the cabman talked on and on, now about a radio he’d bought, now a trapeze artist he’d known, the three-finger waltz he’d learned from his ma, a knife he’d found on the backseat one day, not sharp enough to hurt anyone, a carving knife, like for clay, you understand, for reducing the size of sculptures, for making objects smaller, slowly.

Guy’s not coming, he got around to saying at last.

He’ll be here.

Meter’s running.

I can see that.

He had to be around here somewhere. He still had his usual teaching schedule, four four, comp, business writing, a mild commute. Last time Myers had called (and hung up), Gray had still answered in his despondent voice at both phones—home and office—and there was no sign of anyone picking up and taking off midsemester. That much Myers felt certain of.

What’s that you say? You don’t know what this is about? Maybe a little drill in the earhole will jog your memory. Maybe a little claw of the old clawhammer to the knee. Maybe some takeout, as in, let’s take this outside. As in, let’s take your fingers outside, one by one, toss them out the window. Then let’s see what you know and don’t.

Small satisfactions and, who knows, maybe big ones too.

An hour was going by and then had gone by and another was beginning. Around them, the citizens of Syracuse were dragging themselves home from another day on the make. One got into a sport-utility vehicle two driveways down, his swollen body stuffed inside a coat and slouched under an umbrella. Myers himself was plumped under his own layers of cloth and plastic-based materials.

So what shot you off to Syracuse? the cabman was saying now.

Oh, the usual—vacation, fleeing the cubicle, you know, Myers said.

Odd spot for a holiday.

Friend of the wife.

I don’t see a wife anywhere.

She’s coming later.

The cabman seemed to have chatted himself out. Seemed ready for an explanation from the backseat, by God. He glanced back at Myers. The cabman, fore-armed, seamannish, ex-army. Myers was beginning to despise him.

How much longer you want to wait?

Give him a little, said Myers. Eye on the front door, the driveway, the walk.

I’m turning off the engine.

Leave it on. It’s cold out.

He shut it off.

Hello Gray, good to see you. It’s Myers. So you’re still living alone, I see. Gained a few pounds, put on a few years, lost a hair or two, huh, pal? We sat in the same room for fourteen weeks running once. We gazed at numbers on a board. We bubbled in our Scantron sheets, put down our pencils when done. I suspect your grades were as middling as mine. Maybe worse—you’re dumber. Remember the macaroni, the buttered toast? The jello salad? That’s right, we ate food that came out of the same troughs. I missed my chance to gut you right then.

He had memories of Gray from college days. Gray had appeared some sophomore year and sat in the cafeteria with a backpack. He rifled through papers, scribbled, dog-eared, lined up his bottles of soda. After that he mostly vanished into the public transportation system—Myers recalled a glimpse of him leaning around the bus stop. Myers could remember no award of any sort being given the man. No sailing trophy, no honor roll, no debate club. No special interests, no reading

Mein Kampf

on the quad or passing out religious pamphlets, no part in any play.

What happened to your head anyway? said the cabman.

My head? Myers wiped his nose. Oh, I think I’m coming down with a cold.

Uh-huh.

Gray (he’d say, putting down his briefcase, propping an arm on the doorframe), I rode all the way from New York today. I had the worst day of my life. Six hours on a train will do things to a man. I feel like I’ve got a broken hip now. I feel like I’ve got a broken neck. And I’m tacked to all this suitcase crap. I have to tell you, Gray, for your sake I wish I had a broken neck, I really do. A man with a broken neck knows the thing is over. His enemies are safe. The way it stands now—I hate to say it—for you, it’s not looking good.

The crew cut, the hard face, the cabman. I’m off soon, he said.

Myers could jimmy the door. After all, they had been classmates. It was better than riding all this way and not bothering to confirm he wasn’t here. Better than going as far as the train, as far as the Syracuse depot, the cab, the curb, the mat, and then giving up, not even attempting the house itself. If anyone asked, came prowling by with a shotgun, he could say, Oh, he asked me to drop in, bring in the mail, water whatever stood it, that order of thing.

What else does Myers remember from those college days when Gray was around and Myers ignored him, just let the guy walk on by while Myers was wrapped up in his own bleak affairs, his own muddles? He remembered Gray’s room had been next to the kid who sang on the balcony, the asshole who sang though he had no voice for it, and even if he had, nobody remembered buying a ticket and standing in line to hear any singing, so why did he have to let the whole building in free? Gray had often been half on the scene that way—accidentally present, nearby someone doing something.

In fact Gray had been the most unremarkable student the town had ever seen, and he went that way, unremarked on, through four years of auto-replay days of college and then two more for some other forgettable degree, a brief marriage, a quiet divorce. Myers had found all this out from his own unremarkable seat in front of the computer screen.

Myers hadn’t been spectacular either. He did what he was best at: sat toward the front and took notes. He managed to secure a degree in two pointless subjects (Spanish, design), pointless because, well, he’d never spoken to an actual Spanish-speaking person who wasn’t being paid for the pleasure. But he took care of his library fines, sleeved his degree in plastic, slogged away. That was the last he’d seen of Syracuse. He moved to Brooklyn, rode around on the train in a suit along with everybody else. Took one job, then another. Felt the panic of empty repetitive motion. Then one day he felt like he’d finally found a way to make it all worth waking up for, had met this amazing woman.