Urchin and the Raven War (6 page)

Pennants flew from the tower, swords flashed, cloaks swished. The fighting force was to be made up of squirrels and moles, so it was squirrel and mole families who hugged each other long and tightly. Mothers told their sons and daughters to take care, the sons and daughters laughed, hugged them, and looked forward to the adventure, or pretended to. Animals gathered around Juniper for prayer and blessing. Near the jetty, King Crispin and others of the vanguard—including the mole brothers Tipp and Todd, and Russet of the Circle—sat in gently bobbing boats, speaking with the swans who drifted around them. On the jetty, gazing with yearning at the high white wings of the swans, stood Urchin and Sepia, trying to answer Prince Oakleaf’s questions. Prince Oakleaf was very much like a younger version of Crispin, and full of questions such as “How does that work?” and “How do they know?” Questions Urchin hadn’t thought about and struggled to answer. He couldn’t easily answer “What’s it like to ride a swan?” How could he describe flying?

“Perhaps one day you’ll do it yourself, Oakleaf,” he said.

“Father says swans don’t like being ridden; only if there’s a real need,” said Oakleaf. “Urchin, isn’t that your mum…I mean, your foster-mo…Sorry, I didn’t mean …”

Urchin’s foster mother, Apple, sticking out her elbows, pushed her way through the crowd and waddled along the jetty. It creaked and wobbled a little.

“Never seen—” she began, then stopped to get her breath back. “Afternoon, Prince Oakleaf, ooh, you get more like your father every day, never seen so many swans—hello, Sepia! There’s going to be feathers everywhere when this lot flies off, island’s full of feathers, beautiful feathers, I’ve got some for me hat, don’t get too close to them swans, Prince Oakleaf, just as well they’re going, don’t know how we’d go on feeding them all. I’m right glad you’re not going, Urchin, aren’t you, Sepia?”

Sepia nodded, knowing that there was no point in saying anything, as Apple would go on talking. She was glad, very glad, that Urchin couldn’t go. But Crispin was going, and she felt desperately sorry for Prince Oakleaf. Apple clasped the prince’s paw in both of hers and leaned to look earnestly into his eyes. “Don’t you worry, son, your father’ll soon get the better of them ravens, nasty old birds, they’re only—”

A clang of metal made her, and everyone, jump. The jetty shook. Arran and Fingal had clashed their swords together to call for quiet. Crispin leaped from the boat to the jetty (Apple ducked), and ran to the nearest high rock, where all the animals could see him.

“We leave now,” cried Crispin, “to aid the swans who have been our friends in time of need, and deliver them from the cruelty and injustice that claims their island and attacks their families. Cedar the Queen will be regent while I am away. The captains will advise and assist her and continue their duties as present. Should I not return to you—”

“Oh, it won’t come to that!” whispered Apple.

“—I declare my daughter, Catkin, as the true Heir of Mistmantle, who will rule after me. The queen, with the help of the captains, will be her regent until she is old enough to rule alone, and I ask your support and your prayers for them all. Heart keep you!”

Through the lift and fall of swan wings, Urchin could hardly see Juniper as he limped through the crowd toward Crispin. But he saw the king kneel, and presently Juniper was standing on the rock with his paw raised.

“Heart keep you, swans, creatures of Mistmantle, King Crispin. May the swans of Swan Isle be free and at peace. May all be restored to their own. May this army return safely! Lord Arcneck, King Crispin, we pray for your victory and a joyous homecoming!”

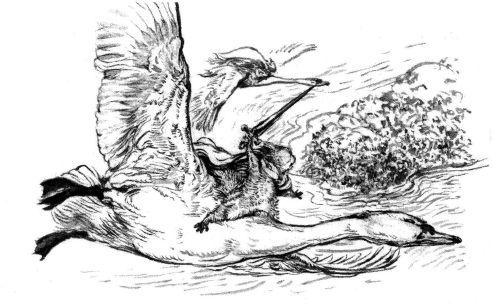

At first Urchin could only see a confused flapping of wings, but the noise of it grew like a calling of drums, and a draft rose that left Apple holding on to her hat with both paws as she gazed open-mouthed. But the swans only flew as far as the shallows, where they settled on the pure blue-green waters, drifting and gliding until they had formed rank upon rank of swans, all with their wings curved high over their backs, their necks arching, and their bright beaks high. From boats and rafts, the Mistmantle warriors mounted.

The watching animals stretched up on clawtips, peering around each other.—

Look, there’s our Chaffie. Look, there’s Mallow, can you see?

—

Oh, look at Trey, he looks so different with his sword…doesn’t he look grown-up?

—

Don’t they look splendid?

There was waving, and dabbing of eyes, and calls carried across the bay.—

Take care, Heart bless you.

—

Come home safely.

—

Don’t worry about me, Mum …

Then the first flight of swans stretched out their necks, skimmed across the water, and, to the gasps and cries of the Mistmantle animals, rose higher and farther, farther and higher, until they were only specks rising above the mists. There were a few sniffs and sighs, and some very young animals saying they were bored and could they go home now? Sepia rubbed her eyes with her paw. Apple sat down heavily.

“Heart bless the king, but it don’t seem right.” She sniffed. “I remember half them guards and archers and that when they were little, it don’t seem right at all, they just want to go on living their own quiet lives and they have to go out and fight them ravens, it’s a terrible thing. And there’s the little ones with their brothers and sisters and uncles and aunties going off with them swans.”

“But not parents, Mistress Apple,” Prince Oakleaf pointed out. “My father said no parents of very little ones were to go—apart from himself, and that’s different, and besides it’s only Almondflower who’s still little. He really does have to go.”

“Heart love him, course he does!” exclaimed Apple. “Never said he didn’t. All the fault of them ravens for starting it. Let me tell you, Your Highness, if I could ride a swan I’d sort them out myself, but I don’t reckon there’s a swan in all the islands could carry me and I wouldn’t want to sink one, would I? Mind you,” she added, “I reckon they’ll have to fly through the night, and won’t they bump into each other?”

“I don’t think they ever do,” said Sepia.

“They’re too clever,” Urchin reassured her. “And the king will attack at dawn.”

It grew late, but nobody in the tower felt like going to bed. They wouldn’t sleep. In the royal chambers, Prince Oakleaf stayed up late, arranging wooden figures of squirrels and moles as Urchin explained the battle strategy to him. Oakleaf had asked where Catkin was, and Urchin had lowered his voice and said, “Secret princess training. So secret that I do’t know where she is. And I mean

secret.

Understood?”

There was a knock at the door so soft that Urchin wasn’t sure he’d heard it, but when the queen called, “Come in,” a very small female mole slipped into the chamber as smoothly as if she were on wheels. She was dark gray rather than black, with bright, happy eyes as she bowed to the queen.

“Oakleaf,” ordered the queen, “go to the turret, please, and see how Brother Fir is. Then you can go to bed.”

“He’ll be asleep,” said Prince Oakleaf.

“Just do it, please,” replied the queen. Prince Oakleaf looked ready to go on arguing, but thought better of it and left the room. The queen and Urchin huddled near to the mole.

“Welcome, Swish!” whispered the queen. “How’s Catkin?”

“She’s all right now, Your Majesty,” said Swish the mole. She had a quick, breathless way of speaking and a ready smile. “Learning to keep her mouth shut, Majesty. Nearly gave herself away once or twice. Stopped herself in time. When the king flew away, she stopped and looked up to watch, same as all the others, but she never said a word.”

“Well done, Swish,” said the queen, and offered her a cordial and biscuits from a tray on the table. “Keep up the good work.”

EAR HUNG IN THE SLOW GRAY

EAR HUNG IN THE SLOW GRAY

dawn over Swan Isle. Deep in reeds and in hidden nests, swans hid their young and watched, their eyes fierce and weary, for the harsh beat of blue-black wings. They sheltered their young from the cruel raven beaks and from the sight of slaughtered swans and shattered eggshells. The island smelled of blood. When mother swans wept for their young, they cried quietly. The squirrels had hidden deep in the trees, rationing out the stores of food, seeking water only from underground or collecting it from the leaves at night. Nothing must attract the attention of the ravens.

When an animal or swan was caught by the ravens, there were two possible endings. The first was to be killed and eaten at once. The second was to be forced to work—

Bring water, more water. Bring meat, more meat, faster. Bury the bones—

until they staggered with exhaustion and were killed, and more animals would be dragged miserably to slavery. Nights were long and days were worse.

Cowl Caw!

The ravens called to each other as they completed each night patrol of the island. Swans and squirrels, just starting to fall asleep, jerked awake. To Pitter, a young squirrel hiding in a tree with her uncle, aunt, and cousins, it seemed that they did it on purpose so that nobody would sleep properly.

Pitter had never known her father. Now she no longer had a mother. So what if her mother had been so careless and lazy that she had never cleaned the nest or prepared food, and Pitter had to do it? So what if she had spent more time with her friends than with Pitter, and never seemed to care where Pitter was? She was my mother, thought Pitter. The only one I could ever have. They had no right to kill her. She imagined herself standing up to the ravens and terrifying them, even fighting the Archraven himself. But, of course, she couldn’t. She hid and cowered with everyone else, and despised herself for it. She lived now with an uncle, aunt, and cousins, who plainly resented her.

Knowing that she wouldn’t go back to sleep, she put both paws to a hole in a tree and peered out, leaning to one side, then to the other. If she pressed far enough to the left, she could just see a corner of the princess’s grave.

Since the ravens had come, hope had drained from the island. Every new day brought wretchedness, and every new day was too long. Like all the squirrels, Pitter looked for little things to bring brightness—a few flowers opening before the ravens could rip them up and use them for nesting; a little sunlight through the leaves before raven wings blocked it out; a mouthful of hazelnuts—and, for Pitter, there was the princess’s grave.

The Swan Isle squirrels were a forgetful bunch, and nobody seemed to know who the princess had been. They just shrugged and said that the neat mound of stones in the clearing near the sea was “the princess’s grave,” but nobody could remember her name.—

It was, you know, her.

—

I think I sort of know who she was.

—

Oh, yes, whats-her-whiskers.

—

If you ask me, she threw herself at that stranger as soon as he got here.

—

Didn’t she wear that gold thing on her head?

There was a story that a squirrel had once come to the island, and he was a prince or a lord or something, and he married a squirrel here, but she died, and nobody could remember what had happened to him.—

Suppose he just went away.

—

Don’t know.

—

Wonder what happened to that gold thing.

—

That was pretty.