Urchin and the Rage Tide (17 page)

“Here’s Grain,” said the king. “He’s been part of Mossberry’s guard today. How’s he doing, Grain?”

Grain bowed, looking nervous. “Your Majesty, he threw his medicine out of the window,” he said.

“Disgusting little article!” muttered Docken.

“Anything else?” asked Crispin.

“He said a terrible judgment is coming.…”

“On the island, he always says that,” said the king. “So apart from that, he’s being reasonable, is he?”

Grain looked at the ground. He clearly wasn’t enjoying this.

“Spit it out, Grain,” said Fingal.

“He said he wanted to fight and kill you in single combat, Your Majesty,” said Grain almost apologetically.

“He’d be making a big mistake,” Padra said to Grain. “I wouldn’t take Crispin on. Best sword squirrel in the island.”

“It’s beneath your dignity to fight him, Your Majesty,” said Fingal. “But not beneath mine, because I haven’t got any. I’ll fight him if you like.”

Crispin smiled. “Thank you, Fingal,” he said, “but nobody is going to fight him. He can stay put and take his medicine. Off you go, Urchin and the search party. You’ll need tools for digging. And, Spade, tell those moles to feel for every vibration. The island seems to be falling down around us just now. Thank you, Grain, you may go.”

There was a scream of rage from Mossberry’s cell.

“Sounded like a six to me,” said Padra. “Add it to your score, Grain.”

“Yes, sir, thank you, sir,” said Grain, and bowed his way out of the room. Presently the meeting broke up, and only the king and queen, Padra, and Arran remained.

“How is that shoulder really, Arran?” asked the queen.

“It’ll do,” said Arran.

“It’s worse than you’re telling us,” said Crispin. “All of us here know that.”

“Pardon me, Your Majesty,” said Arran, “but your old wound from the Raven War is worse than you’re telling us. You don’t make a fuss, and neither will I.”

“I can’t do a thing about the king’s injury,” said Queen Cedar, “but maybe I can about yours.” But when she had pressed Arran’s shoulder at different points, and asked her to clench her paws and raise and lower her arm, she finally said, “I can ease the pain and stiffness, but it’ll never be the same again. You’ll always have problems with it.”

“That’s what I thought,” said Arran. “It really is time to hang up my circlet, Crispin.”

“Your circlet is yours until the day you die,” said Crispin. “But I know you want to be relieved of your duties as captain.”

“I’ll stay until the worst is over,” she said. “Then I’ll help Fionn with her refuge for lost frogs, or whatever she thinks she’s doing. She seems to be adopting them.”

“I couldn’t ask for more,” said Crispin.

Later that day, two hedgehog guards took salad and cordial to Mossberry’s prison cell, set it down on the table, and waited to see if he would eat it, or throw it on the floor. He must have been hungry, because he ate.

“Do you see how the Heart provides for me?” he said. “The Heart sends me all I need!”

“The queen sends you all you need,” said a hedgehog.

“The queen sent it?” repeated Mossberry.

He sipped at the cordial and, when they had gone, threw it out of the window. Typical trick, he thought. It’s some foul potion that the so-called queen has sent me. She’s trying to keep me quiet because she is evil and I have found her out. The Heart is against her. Her evil tower will fall about her in flames. He imagined the queen trapped in the tower with fire roaring all around her. The thought of fire excited him, so that he wrenched and heaved at the window bars in frustration and, at last, curled up on the floor and rocked, feeding his imagination with thoughts of fire.

After nights of navigating by the stars and sleeping little, Corr saw land. The sight lifted his heart with joy, and he found new energy to go on rowing. His muscles had grown strong and hard in his journey.

He had heard about Swan Isle—Urchin had told him about it—but this didn’t look quite like the island Urchin had described. Maybe he was approaching from a different direction, but, as he turned the boat and drew nearer, it seemed too bleak and bare to be the home of swans. As the boat ran aground he leaned over the oars to scan the shoreline.

Something moved. Something on the ground uncurled itself and raised a small, searching head that turned to and fro. Then another. A hiss, and a slither—

Snakes! He swung the boat around and rowed furiously, putting clear water between himself and the snakes. When the first anger and disappointment wore off, he remembered something else Urchin had said: Crispin, when he went to Swan Isle, had landed first on a snake-infested island. At least this proved that he was in the right area. Crispin had reached Swan Isle, and so would he. He tasted the air again, leaned over to trail a paw in the water, then rowed on. When he had drifted into sleep, light rain woke him, and he sat up, rubbing his aching shoulders.

A wreckage of leaves, twigs, and blossom floated on the sea around him. Before him was a windswept island of bent and broken trees, where a silver stream curled its way to the shore.

“Heart help me,” said Corr. “It has to be Swan Isle.” The position of the spring and the shape of the bay were exactly as Urchin had told him, but from the look of the trees and the scattered foliage on the water, the rage tide must have hit this island savagely. At least, this time, he couldn’t see any snakes.

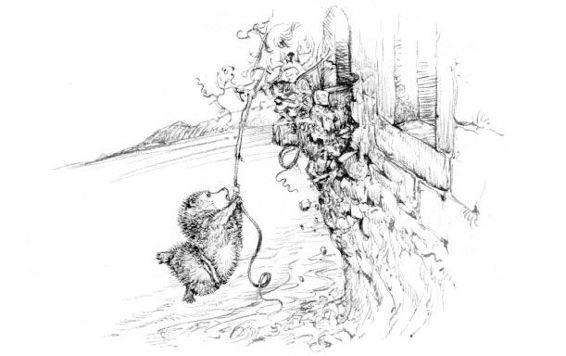

He rowed to the shore and slipped into the sea, rolling for joy in the shallow waves, feeling the salt water on his fur. Then he heaved the boat on to dry ground, tied the rope to a tree, and plodded stiffly uphill. Once he caught sight of a squirrel, but when he called to it the squirrel only shrieked, put a paw to its mouth, and ran away; so Corr climbed on uphill, stepping over fallen branches, until he came to a lake.

Three or four swans floated there, bending their necks to feed. Leaves and twigs drifted on the water and clung to their disheveled feathers. Around the shore, parents guarded their nests.

He was about to call out a greeting when a flapping of great white wings in his face terrified him. He sprang back, holding out his paws to show he was unarmed as two swans flew at him.

“I’m harmless!” he cried. “I won’t hurt anyone! I came to find Prince Crown—I’m an otter of Mistmantle!”

The two swans still bent over him with fierce, strong beaks, but they did not attack him. Even with tired eyes and ruffled feathers, they were daunting.

“Mistmantle?” asked one. “Are you a friend of King Crispin?”

“Yes!” he said.

“And of Urchin of the Riding Stars, the friend of swans?”

“Yes, I serve Urchin,” he said.

“Did you fight the ravens?”

“Yes!”

“Then you may meet Lord Crown,” said the first swan. “You called him Prince Crown. He is Lord Crown now.”

As they spoke, something swished behind them. Corr looked past them to see a swan with a ring of gold feathers around his head settle onto the water.

“Pri…Lord Crown!” said Corr.

“An otter!” said the new swan gladly, as the others curved their necks to bow to him. “A Mistmantle otter! You are most welcome! Our hospitality may be poor at this time, but it is good to see a Mistmantle animal!”

Corr could tell that the welcome was warm and genuine. But he saw, too, that Crown was exhausted, and trying, not quite successfully, to hide it.

“Prince—Lord Crown,” he said, and bowed. “I’m Corr, Urchin’s page.”

“Yes, I’m Lord Crown now,” said Crown gravely. “My father, Lord Arcneck, died in the rage tide.” He inclined his head toward the other two swans to dismiss them. “Did it strike Mistmantle, too?”

“Yes, sir,” said Corr, but even Mistmantle hadn’t looked as devastated as this. “I’m sorry to hear of your father.”

“Come to the shore,” said Crown. “The water there will suit you better.”

Corr followed him uneasily, beginning to wish he hadn’t come. It had seemed sensible to look for Sepia on Swan Isle, but now, seeing its devastation, he felt he was intruding on their tragedy. Swan Isle had enough troubles of its own. He slipped into the littered sea, and Crown glided beside him.

“So,” said Crown, “what has the rage tide done to Mistmantle?”

“It’s swamped crops, trees, homes—anything in its way,” said Corr. “The king and the Circle managed to keep most of the animals safe. It must have been far worse here. But, please, Lord Crown, I have an errand. Do you remember Sepia from our island? Sepia of the Songs?”

“Sepia,” repeated Crown thoughtfully. “I remember her voice. I saw her leading the little singers.” He tilted his head, and to Corr he looked far older and sadder than he should. “What happened? Did the rage tide take her?”

Corr hesitated. “Yes,” he said. “At least, it swept her away, but she might still be alive. That’s why I came. She was swept out to sea and through the mists, clinging to a boat, and nobody could reach her. I had hoped she might be here, but…”

“For everyone’s sake, I wish she were,” said Lord Crown. “But if she were on this island, I would have known.”

So that was that. Corr tried to think of something to say, but there was nothing. If Sepia had not arrived on Swan Isle, he had no idea where else to look. It was as if she had sailed out of sight forever.

“Believe me,” continued Crown, “if she had landed here, she would be cared for as an honored guest. But what about you—you have left Mistmantle by water to find her! You must have left Mistmantle forever for this quest!”

“I’m a Voyager, sir,” he said. “I can come and go freely through the mists. If I can find her, I can get her to them.”

“And then?”

Corr wished even more that he hadn’t come. He had meant to ask if a swan could carry her over the mists for him. It had seemed so simple when he had first worked it all out, but these swans had suffered so terribly in the rage tide that he couldn’t possibly ask for their help. Perhaps Whitewings could provide a swan. The thought of rowing all the way back there, then to Mistmantle, seemed to knock the strength out of him.

“I understand,” said Crown. “You hoped that one of us could take her home. Mistmantle and Swan Isle have helped each other ever since Crispin landed here in exile, and I know how your island suffered in the Raven Wars. Rest here, Corr. Fish. Drink from our streams. Be refreshed. Hold on to your hopes. Let me talk to my swans.”

Corr slept in his boat that night, warm under the yellow cloak. Sometimes he woke thinking he was out at sea and needed to look up to read the stars—then he would remember where he was, and drift into sleep again. The sun had risen when the prodding of a strong beak dragged him reluctantly awake.

“Corr!” Lord Crown was nudging him, shaking the cloak from him. Corr uncurled and rubbed his eyes, hoped he was being awoken for a good reason.

“I have news for you, Corr,” said Crown.

Corr sat up. Lord Crown stretched his wings, standing on the prow of the boat.

“I have spoken to my swans,” he said. “One, who has returned from a long flight, reports seeing a boat—an animal appeared to be sleeping in it.”

“That could have been me,” said Corr, trying not to yawn.

“No—not in those waters,” said Crown. “And I have talked to our squirrels. If she’s alive, I know where she may be.”

The tiredness fell from Corr like an unclasped cloak. This time, this time, had he found her?