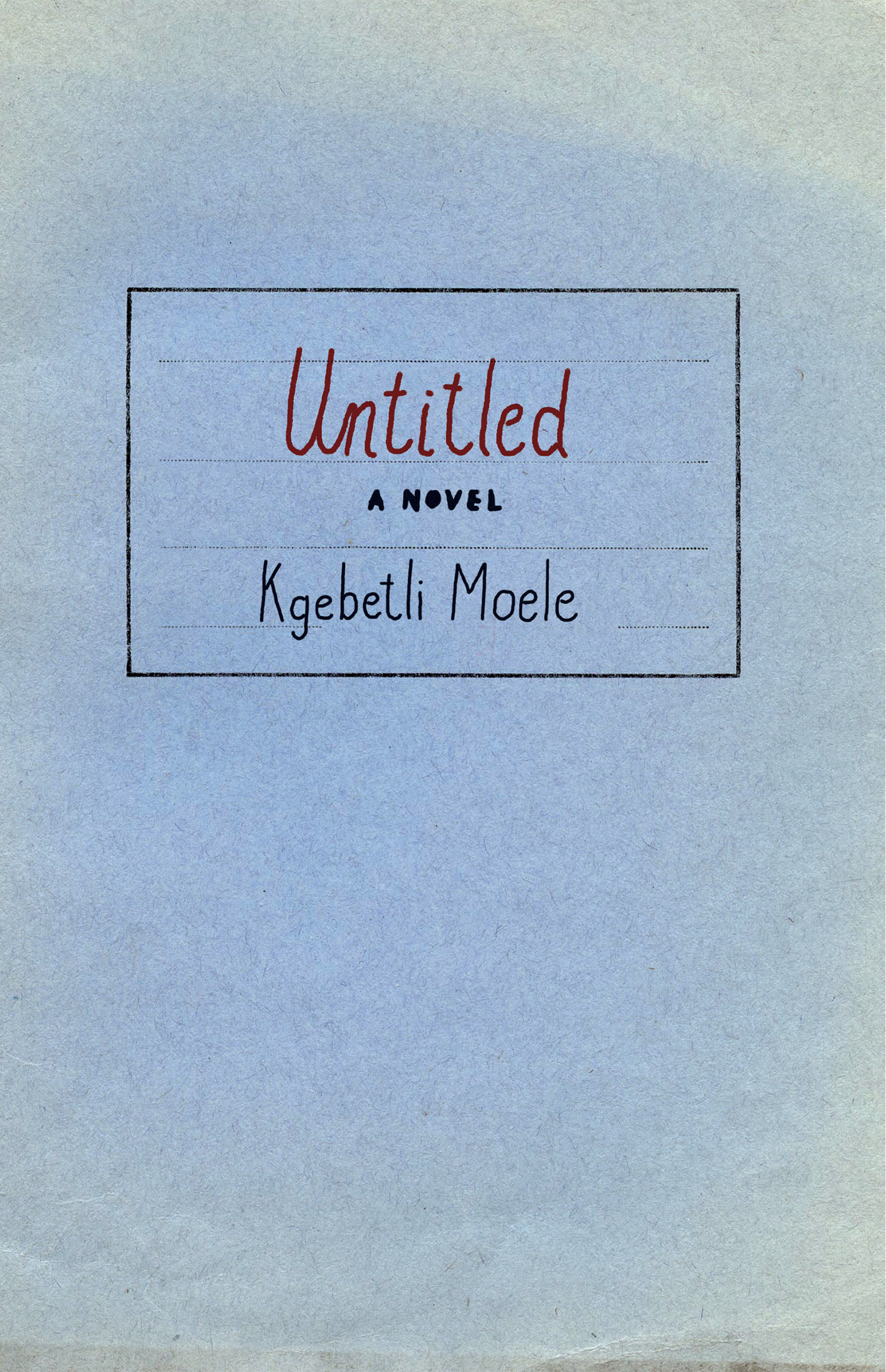

Untitled

Authors: Kgebetli Moele

Tags: #Room 207, #The Book of the Dead, #South African Fiction, #South Africa, #Mpumalanga, #Limpopo, #Fiction, #Literary fiction, #Kgebetli Moele, #Gebetlie Moele, #K Sello Duiker Memorial Literary Award, #University of Johannesburg Prize for Creative Writing Commonwealth Writers’ Prize Best First Book (Africa), #Herman Charles Bosman Prize for English Fiction, #Sunday Times Fiction Prize, #M-Net Book Prize, #NOMA Award, #Rape, #Statutory rape, #Sugar daddy, #Child abuse, #Paedophilia, #School teacher, #AIDS

Kgebetli Moele

UNTITLED

KWELA BOOKS

Â

Veronica Mhlongo

(She died)

Late Saturday night, the 7th of August, I am trying to express myself in a poem, as I like to when I am in a situation. Usually, expressing myself in a poem helps me to see a way forward, but now I am in difficulty. For this poem I had the last line before I could even title it. Long before I picked up a pen, the last line was going round and round in my mind, like a computer screensaver, and so I wrote it first at the bottom of the page:

I now pronounce myself deflowered

This line came, it just came, but now I am trying to think what I can call this verse. What title can I give this verse about me? “Mokgethi”?

Yes, Mokgethi is my name, so why not call it “Mokgethi”?

No. Mokgethi is my name, but the poem is about part of Mokgethi. Mokgethi is a me that I came to know and understand and there is still a future Mokgethi that I do not know, do not understand as yet. But this verse has a last line â it is already complete before it even started. Mokgethi still has a way to go before she can come to an end.

What about “Mokgethi at Seventeen”?

Good but not making it.

“How I Lost My Virginity.”

Hmm ... That is too blunt and degrading.

“A Woman Alone”?

There is a book called

A Woman Alone

.

What about “A Girl Alone”?

No.

“One Saturday Afternoon”?

No.

“Saturday the Seventh of August”?

No, that does not sum it up.

After much thinking and wasting time, trying to come up with a suitable title for this verse, I resort to calling it “Untitled” and write

Untitled

at the top of the page:

Untitled

“Untitled” because I don't know what to call this verse about me. “Untitled” because even though I knew that it was coming, I didn't expect it to be this way. “Untitled” because it has elements that I do not know properly yet, elements that scare me because I do not know what the Mokgethi of tomorrow is going to be like.

The future has always been scary but I always thought that if I planned ahead, well ... Now I know that you cannot plan for the future and, as I have come to experience, you cannot expect it to be the way you want it to be.

“Untitled” because I fear the coming Mokgethi, for I don't know what she will become. Because this new Mokgethi has not been defined yet and Mokgethi was comfortable â happy, even â with being Mokgethi before sixteen hundred today. Though physically this Mokgethi and that Mokgethi are one and the same, they will be very different in character. I do not know how much the character of the Mokgethi that I so loved being will remain with me after today. The difference between them is what scares me. I loved Mokgethi the innocent girl; she was upright and always ahead. Things didn't concern her too much; she could listen when she needed to listen, laugh when laughter was the thing required. She could try to give comfort when it was needed and she could be amazed when something was amazing.

The old Mokgethi was time conscious; she respected time most of all. Though there were a few things in her life that were difficult for her to say out loud â things she couldn't really understand â she understood all the important aspects of her life. She had goals, dreams and a vision. The old Mokgethi was happy with herself and if she had been granted one wish, she would have wished to remain Mokgethi the virgin. Why? Because I have seen all the girls that I know lose themselves, thinking that they understand their lives but only understanding the surface. They all blur into one. Once a girl loses her innocence, it becomes “My man this ... My man that ...” They start identifying themselves with their man and judging themselves through the eyes of the men. Then they start to fight and quarrel over what they think are the best men available. At the end of it all one is left with a fatherless child and the realisation that you have wasted your time. Hating all men because they have failed to find the right, the best man for themselves. They are on welfare, looking at “My man this ... My man that ...” from a very different angle. But they cannot start over again. They are caught in the tide.

I am writing this verse to try to understand the coming Mokgethi. Trying to find a way for her to live comfortably with herself. She will have to enjoy being this Mokgethi first, just as the murdered Mokgethi enjoyed being Mokgethi ...

PART ONE

Mokgethi

When I discovered myself I was opening a door â maybe I was four, maybe not â and the other person said:

“Mokgethi.”

Then I said:

“Ha!”

That was it,

me

, and to this very day Mokgethi is the name that they are calling me with. I found myself being Mokgethi and I had to discover and make this Mokgethi out of what they named Mokgethi. I tried very hard to make a Mokgethi that I, as Mokgethi, would love, a Mokgethi that I was happy and comfortable with.

I was born in 1996 on the 19th of August at 12:03 pm exactly. If you are clever enough you can calculate that this means that sometime during the third week of November the previous year, my dad and my late mother were enjoying the windiness of late autumn and I was what they achieved.

I am her first-born but I am not sure if I am his first-born, just as I am not sure if I just happened or if they were planning to have me.

There is not much that I can say about my parents. Everything I know of them comes from a few black-and-white photos that don't tell me much, though I have spent too much time wishing that they could talk to me, so that I could understand them, my parents, and feel their love.

At times I wish I could ask them why they gave me the name Mokgethi â one's name makes one; it connects and influences the character â as there is nobody else I can ask who knows and will tell the honest truth.

In this picture my mother is nestled deep in the arms of my father. For a long time I wasn't sure that he was my father, even though my grandmother said that he was, but now I do believe her. My mother is resting in his arms as if nothing matters. It is as if she has reached the realm of the gods, totally and completely, like she has lost all sense of herself, and that is why I am here, and my brother Khutso is here, and between us is a gap of only twenty months.

My mother is no more; she left us, passed away when I was just four years old. She had a BA in social work from the University of the North. I was born exactly four months after she graduated; her degree certificate hangs on the back of my bedroom door. I don't know who put it there but it has been there since I came into my consciousness. At times I thought that this degree was my inheritance, all that she left me. Long time ago, when I was still small, naive, I used to think that when I was older I would just take it and it would be mine.

When she met her death my mother was working as a social worker in Lebowakgomo. They say that my mother was a queen; she was beautiful:

“Hauw! Mokgethi, you are the daughter of the late MmaKhutso; you are trying but she was the most beautiful of creations.”

Then they tell that my mother was a bookworm and she loved reading romantic novels, and that she was the most fashionable woman in the whole township back then. There is a photo where she is wearing huge goggles and some seventies or eighties fashion; she looks like something from a Leon Schuster film, but I am told that it was the “in thing” in those times.

Although no one has ever really told me straight, I know that when she passed away we were living as a family. They â my parents â were married legally, though without the knowledge of their families. The law back then didn't allow an unmarried woman to occupy a government position, so my parents got married without telling their families because they were protecting my mother against the law. When they came to explain to their families, well, maybe my maternal family didn't want to understand their reasons why and just because my mother was educated they thought somehow ...

I cannot say what happened but I know that my parents continued living together and we â Khutso and I â were there, living with them. My paternal family tried to bring the families together and pay lobola, but my maternal family asked how my paternal family proposed to negotiate the marriage of people who were already married. My paternal family thought that the issue would eventually work itself out but it never did.

My brother, Khutso, had just turned two and I was nearing my fourth birthday when, one Saturday morning, it happened. We were playing with our father as our mother was in bed. She sent us out to buy her some headache tablets. When we came back, she was no more.

We have been living with our maternal family ever since. My dad has been living somewhere else â not that he hates us, but my grandmother, my uncle and my aunt do not allow him to see us for some reason that I do not know. They don't want to tell me yet or maybe I will never know, but I do know that he is paying maintenance. I know this because a few years ago my grandmother took us to a local social worker to claim orphan welfare grants. The social worker asked why we needed the grants as we were receiving maintenance every month from our father. My grandmother tried to deny this, but the social worker told her exactly how much money our father was contributing every month. At this, my grandmother got very angry and stayed angry until she went to sleep. The next day she pretended that nothing ever happened.

Maybe they are afraid that he will take us away from them?

Probably he has another wife and kids.

Somehow I do not wish this statement to be true. It is something I hope to be false.

Mamafa told me that my father is a magistrate in Polokwane. I cannot say how exactly I felt when he told me this, but I was overwhelmed, a bit like my mother in this photo.

I am still young, very young, this I know, but my maternal family treats me like I am an infant. No one tells me anything and I have had to learn a lot of things on my own. They are very secretive, even about things that affect my life.

“You are going to a private school.”

I got very excited, went to private school for three years and had the best time.

“You are not going to private school next year. You will be going to the local high school.”

I got disappointed but what could I do? I went to a public school to do Grade Eleven and came to accept this hell of a school as my own.

“You are going to live with your aunt.”

I went and lived with my aunt, though I did not want to. Then some boy came to the house looking for me and after that she got fed up of living with me and chased me back to my grandmother's.

My aunt Sarah gave me three hundred rand every month from Grade Eight. She stopped when I stopped going to private school without giving a reason why.

At the private school they were paying four thousand rand tuition per month. Though nobody ever told me who was paying for this, my cousins â Aunt Sarah's daughter and all three of Aunt Shirley's children â were going to private schools as well, so I didn't think it strange. They are still in private schools, even though Aunt Shirley is not working this year as she is going to university. Aunt Shirley is building a house as well and after I left the private school she took my bank card without giving any reason. The few times that I dared to ask about it she got angry, saying that I didn't need it.

“But it is my bank account,” I protested.

“Mokgethi, you are not working and you do not have money in it. Do not start to irritate me.”

Everything came to a head after the meeting we had with the social worker. My grandmother gets angry when she feels I want to know about something that she thinks I should not know about.

I told Mamafa my troubles only as a supportive friend, but he said that we were going to know the truth somehow. He asked my dad's name, giving me some comfort by saying that he will find him for me. This was on a Sunday afternoon and I cannot say how but on Monday he tells me that he has his numbers.

“Sorry, sir, what I am about to tell you may come as a surprise. Please, do not think anything other than that I am trying to help a friend of mine.”

He was talking to my father over the phone. Then he gave him my numbers.

About the bank card: Mamafa called the lost card number and they blocked it. He told me that the operator had told him that some money had been withdrawn from the account a few hours before he'd called. He then said that we should wait until whoever was using the card came to tell me that it had been swallowed by the teller machine. Mamafa expected that this wouldn't take too long and it didn't. Three days later Aunt Shirley called me. She was trying very hard to be humble, but I could tell that behind the humbleness and sweet begging voice she was as angry as hell. Maybe she had gone inside the bank to complain and had been reminded that she was not Mokgethi.

At the bank they told me that the account had about two thousand rand in it and from the statements it was obvious that seven thousand was being transferred into it on the last working day of every month. Of that, one thousand four hundred rand was then transferred into two different accounts and the rest was used by the holder. Before I left the bank I was tempted to ask who the two account holders were and where the money came from but my heart told me to just shut up and take the card.

The next day Aunt Shirley came personally to pick up the card. She was the sweetest person on earth that day, smiling at everyone, and for the first time I noticed that she was a beautiful woman. She left me wondering if even inside monsters there is a degree of sweetness and care.

Mamafa couldn't understand why I gave the card to Aunt Shirley, but that's what I did. I had my own plan of action â I was going to find out where the money was coming from, who it was for and whose accounts the one thousand four hundred rand was being transferred into.

“When?” Mamafa asked.

“When the time is right.”

My father called me soon after that and for the first time in all my conscious life I had a conversation with my own dad. He gave me his brother's numbers and said that if I needed anything I should call him. Though I was not that happy with the set-up there was nothing I could do about it.

Mamafa justified the rabbit's habits, talking like he knew everything:

“Well, Mokgethi, the reasons are clear to me. It's because your father has a wife and kids and somehow he forgot to tell your beautiful stepmother that you are breathing too. And after how many years? You just do not know how people handle things and your father is a magistrate and has to live a clean life so he can end up as a high court judge.”

“Why cannot he just tell her about us? We are his children.”

“Maybe he has too much to lose by revealing you.”

“What would he have to lose?”

“We will understand with time.”

I was still puzzled and in some darkness.

“Maf?”

“Mokgethi, what did you expect? To pack your bags and just go live with your father? That can never be. Just be happy that you know your father and I believe he is equally thrilled to know you.”