Under a Wild Sky (30 page)

Authors: William Souder

Audubon had reached the end of all the rivers he had been on since he and Lucy had set out for the frontier on their honeymoon. Now it seemed he could go no farther. Seeing and drawing the birds of America remained his goal, but he no longer had any clear idea of how he would achieve it. Desperate for money, Audubon looked for work as a portrait painter and found a little. In one ten-day stretch during his first month in

town, Audubon managed to earn $220. He resolved to stop blaming his circumstances on poor luck and to instead become a “wiser” man. But it would be a long time before he was a happy one again. For the next several years, even after being reunited with his family, Audubon would bide his time in Louisiana, painting and teaching, working and waiting for something good to happen.

Audubon didn't care much for New Orleans, though it was the cultural capital of the southwest and home to many painters and musicians.

New Orleans was the fifth-largest city in the country and second only to New York in shipping tonnage.

The city was also a principal immigration point and on the way to becoming the country's leading slave trading center. The population of 27,000 featured a mélange of skin tones and dialects that Audubon found disagreeable, as well as odd social arrangements between the races, many seemingly contradictory and difficult to sort out. There were, of course, many slaves in Louisiana. But there were also a fair number of free people of color.

Almost incomprehensibly, a few of these free blacks actually owned African slaves. Everywhere there was evidence of the mixing of races and peoples. Audubon was fascinated by the weird speech of the Cajuns, who spoke what seemed a backcountry blend of French, Spanish, and English, but he was not impressed by their knowledge of the country. Early in his stay, Audubon reported seeing on the streets some pretty “white ladies,” though he also admitted to being curious about a “quatroon ball,” as he called it, which he would have attended but for the $1 admission.

Quadroon balls were popular events at which women of mixed race mingled with white men. In fact, relationships between white men and mulatto womenâas long as they stayed short of marriageâwere widely accepted and often arranged by the young women's mothers. Women of color were especially popular as mistresses to prominent white men, who provided for their paramours in accordance with the implicit social code. All of this was not unlike the laissez-faire attitude back on Saint-Domingue, and it may be that New Orleans reminded Audubon uncomfortably of his own heritage. In any case, Audubon said he much preferred “rosy Yankee or English cheeks” to the many “citron” faces he encountered in the city.

But the countryside around New Orleans more favorably impressed Audubon. The land here was flat in a way that sometimes reminded him of France, and the typically warm weather made the vegetation lush.

More important, southern Louisiana teemed with birds, both locals and migrants that overwintered there. Birds of every description could be seen in the New Orleans market, though it was in Audubon's estimation the “dirtiest place” in any city in America. The market's filthy stalls sometimes made him wish he'd remained in Natchez, but Audubon could not stay away from the daily display of so many members of the “feathered tribes.” Ducks and geese and herons could usually be had, plus an ever-changing assortment of songbirds. Audubon was dismayed at some of the pricesâ$1.25 for a brace of ducks seemed outrageousâbut amazed at how cheaply other species could be bought. One day he found a freshly cleaned barred owl for only twenty-five cents.

The Mississippi River between New Orleans and Natchez was flanked by plantations that grew mainly sugar and cotton. Both were labor-intensive crops. As more and more African slaves arrived, the plantations grew in size and prospered. When word of his skill as a portrait painter spread, Audubon started getting work at some of these country estates and from the businessmen who traded with them. Usually the job began as an assignment to paint the woman of the house. Some of the wealthy and bored plantation wives found Audubon's presence pleasant enough to ask him to stay on and paint other family members or offer drawing instruction to their children. Audubon leapt at these opportunities, but soon learned that these temporary positions required more patience and diplomacy than he had to give. The women were sometimes fickle and could be cruel when they grew tired of him or thought him insufficiently attentive. Some of the children were ill-behaved or without talent. In a few instances, his clients grew uncomfortably close to the poor but still dashing Audubon. Women talked among themselves about how handsome and clever he was.

One bit of gossip hinted that Audubon was a philanderer and no longer cared for his wife, whom he supposedly said had begun to show her age “like a beautiful tobacco plant cut at the stem, and hung to wither.”

But Audubon had little choice about what to do with himself. The jobs sometimes included room and boardâwhich was important, as on several occasions he was unable to collect the agreed-upon salary. These engagements also left Audubon time to explore the fields and swamps and continue his own work. By mid-February, Audubon had completed twenty new drawingsâincluding four of birds “not described by Wilson”âwhich he sent north to Lucy.

In this dashing self-portrait made shortly after his arrival in England, Audubon looked the conquering hero. His nervous caption was closer to the mark. (John James Audubon,

Self-Portrait

, 1826, pencil on paper. University of Liverpool Art Gallery and Collections)

Mill Grove. Audubon's first American home, where he invented his technique for drawing birds to scaleâand where the girl next door was a pretty young Englishwoman named Lucy Bakewell. (Used by permission of the Mill Grove Audubon Center's Archives)

This unpublished painting of the belted kingfisher, made by Audubon at Louisville in 1808, hints at the enormity of his talent, although this simple profile is not characteristic of his mature style. (Used by permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University)

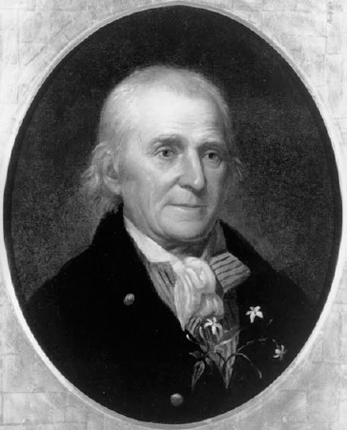

William Bartram, the eminent Philadelphia botanist and mentor to Alexander Wilson. Bartram's accounts of his expeditions to Florida before Audubon was born were among the first and most important natural history studies undertaken by an American. (Portrait by Charles Willson Peale, 1808. Used by permission of Independence National Historical Park)

The house at Bartram's Garden, where Alexander Wilson taught himself ornithology. (Used by permission of the American Philosophical Society)

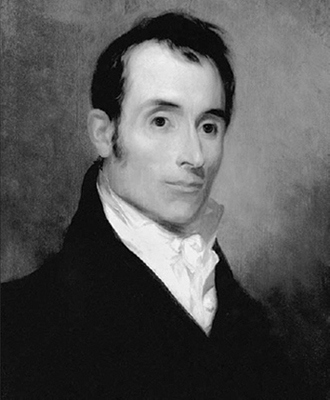

Alexander Wilson. Complicated, morose, brilliant, he created

American Ornithology

as the first attempt at a comprehensive description of the birds of the New World. (Portrait by Rembrandt Peale. Used by permission of the American Philosophical Society)

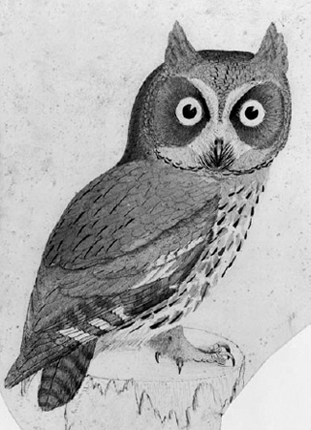

Wilson taught himself to draw birds by practicing studies of a stuffed owl such as this one. The flat, immobile pose was the accepted method for ornithological depictionsâuntil Audubon changed everything. (Used by permission of the Ernst Mayr Library of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University)