Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption (57 page)

Read Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption Online

Authors: Laura Hillenbrand

Tags: #Autobiography.Historical Figures, #History, #Biography, #Non-Fiction, #War, #Adult

At first he recognized none of them. Then, far in the rear, he saw a face he knew, then another and another: Curley, the Weasel, Kono, Jimmie Sasaki.

And there was the Quack, who was petitioning to have his death penalty commuted. As Louie looked at this last man, he thought of Bil Harris.

There was one face missing: Louie couldn’t find the Bird. When he asked his escort where Watanabe was, he was told that he wasn’t in Sugamo. Over five years, thousands of policemen had scoured Japan in search of him, but they had never found him.

As Louie had been packing to come to Japan, the long-awaited day had arrived in the life of Shizuka Watanabe: October 1, 1950, the day her son had promised to come to her, if he was stil alive. He had told her to go to the Shinjuku district in Tokyo, where he would meet her at the same restaurant where they had last seen each other, two years before. At 10:05 that morning, police saw Shizuka climb aboard a train bound for the Shinjuku district. At the restaurant, Mutsuhiro apparently never showed up.

Shizuka went to Kofu and checked into a hotel, staying alone, taking no visitors. For four days, she wandered the city. Then she left Kofu abruptly, without paying her hotel bil . The police went in to question the hotel matron. Asked if Shizuka had spoken of her son, the matron said yes.

“Mutsuhiro,” Shizuka had said, “has already died.”

In the corner of a sitting room in her house, Shizuka would keep a smal shrine to Mutsuhiro, a tradition among bereaved Japanese families. Each morning, she would leave an offering in memory of her son.

——

In Sugamo, Louie asked his escort what had happened to the Bird. He was told that it was believed that the former sergeant, hunted, exiled and in despair, had stabbed himself to death.

The words washed over Louie. In prison camp, Watanabe had forced him to live in incomprehensible degradation and violence. Bereft of his dignity, Louie had come home to a life lost in darkness, and had dashed himself against the memory of the Bird. But on an October night in Los Angeles, Louie had found, in Payton Jordan’s word, “daybreak.” That night, the sense of shame and powerlessness that had driven his need to hate the Bird had vanished. The Bird was no longer his monster. He was only a man.

In Sugamo Prison, as he was told of Watanabe’s fate, al Louie saw was a lost person, a life now beyond redemption. He felt something that he had never felt for his captor before. With a shiver of amazement, he realized that it was compassion.

At that moment, something shifted sweetly inside him. It was forgiveness, beautiful and effortless and complete. For Louie Zamperini, the war was over.

——

Before Louie left Sugamo, the colonel who was attending him asked Louie’s former guards to come forward. In the back of the room, the prisoners stood up and shuffled into the aisle. They moved hesitantly, looking up at Louie with smal faces.

Louie was seized by childlike, giddy exuberance. Before he realized what he was doing, he was bounding down the aisle. In bewilderment, the men who had abused him watched him come to them, his hands extended, a radiant smile on his face.

ON A JUNE DAY IN 1954, JUST OFF A WINDING ROAD IN California’s San Gabriel Mountains, a mess of boys tumbled out of a truck and stood blinking in the sunshine. They were quick-fisted, hard-faced boys, most of them intimately familiar with juvenile hal and jail. Louie stood with them, watching them get the feel of earth without pavement, space without wal s. He felt as if he were watching his own youth again.

So opened the great project of Louie’s life, the nonprofit Victory Boys Camp. Beginning with only an idea and very little money, Louie had found a campsite where the bargain-basement rent compensated for the general dilapidation, then talked a number of businesses into donating materials. He’d spent two years manning backhoes, upending boulders, and digging a swimming pool. When he was done, he had a beautiful camp.

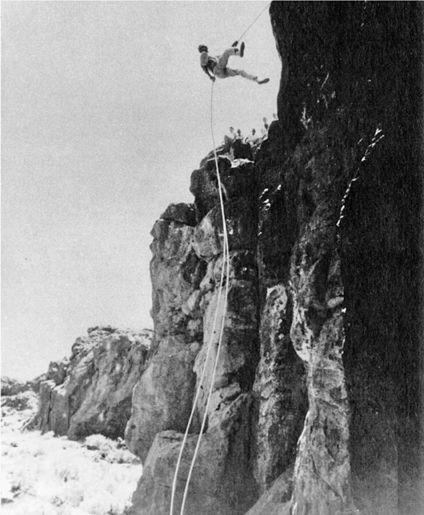

Victory became a tonic for lost boys. Louie took in anyone, including one boy so ungovernable that Louie had to be deputized by a sheriff to gain custody of him. He took the boys fishing, swimming, horseback riding, camping, and, in winter, skiing. He led them on mountain hikes, letting them talk out their troubles, and rappel ed down cliffs beside them. He showed them vocational films, living for the days when a boy would see a career depicted and whisper, “That’s what I want to do!” Each evening, Louie sat with the boys before a campfire, tel ing them about his youth, the war, and the road that had led him to peace. He went easy on Christianity, but laid it before them as an option. Some were convinced, some not, but either way, boys who arrived at Victory as ruffians often left it renewed and reformed.

Louie demonstrates rappel ing to his campers. Courtesy of Louis Zamperini

When he wasn’t with his campers, Louie was happily walking the world, tel ing his story to rapt audiences in everything from grade school classrooms to stadiums. Improbably, he was particularly fond of speaking on cruise ships, sorting through invitations to find a plum voyage, kicking back on the first-class deck with a cool drink in hand, and reveling in the ocean. Concerned that accepting fat honoraria would discourage schools and smal groups from asking him to speak, he declined anything over modest fees. He made just enough money to keep Cissy and her little brother, Luke, in diapers, then blue jeans, then col ege. On the side, he worked in the First Presbyterian Church of Hol ywood, supervising the senior center.

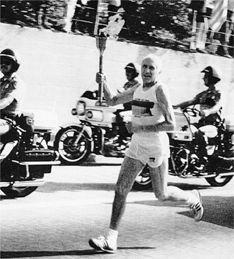

Over the years, he received an absurd number of awards and honors. Lomita Flight Strip, which had been renamed Zamperini Field while Louie was languishing in Naoetsu, was rededicated to him not once more, but twice. A plaza at USC was named after him, as was the stadium at Torrance High. In 1980, someone named a great big barge of a racehorse after him, though as a runner, Zamperini was no Zamperini. The house on Gramercy became a historic landmark. Louie was chosen to carry the Olympic torch before five different Games. So many groups would clamor to give him awards that he’d find it difficult to fit everyone in.

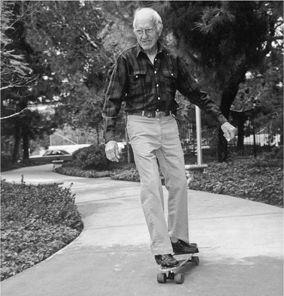

His body gave no quarter to age or punishment. In time, even his injured leg healed. When Louie was in his sixties, he was stil climbing Cahuenga Peak every week and running a mile in under six minutes. In his seventies, he discovered skateboarding. At eighty-five, he returned to Kwajalein on a project, ultimately unsuccessful, to locate the bodies of the nine marines whose names had been etched in the wal of his cel . “When I get old,” he said as he tossed a footbal on the Kwajalein beach, “I’l let you know.” When he was ninety, his neighbors looked up to see him balancing high in a tree in his yard, chain saw in hand. “When God wants me, he’l take me,” he told an incredulous Pete. “Why the hel are you trying to help him?” Pete replied. Wel into his tenth decade of life, between the occasional broken bone, he could stil be seen perched on skis, merrily cannonbal ing down mountains.

Louie on the torch run for the 1984 Summer Olympics. Courtesy of Louis Zamperini

Louie, skateboarding at eighty-one. Courtesy of Louis Zamperini

He remained infectiously, incorrigibly cheerful. He once told a friend that the last time he could remember being angry was some forty years before. His conviction that everything happened for a reason, and would come to good, gave him a laughing equanimity even in hard times. In late 2008, when he was about to turn ninety-two, he was moving a slab of concrete on a dol y down a flight of stairs when the dol y wheels broke, sending Louie and the concrete crashing down the steps. He wound up in the hospital with a minor hip fracture and a shattered thumb. As his daughter came down the hospital corridor toward his room, she heard shouts of “Hey Louie!” from the crowd of friends that her father had made among the hospital staff. “I never knew anyone,”

Pete once said, “who didn’t love Louie.” As soon as he was out of the hospital, Louie went on a three-mile hike.

——

With the war over, Phil became Al en again. After a brief stint running a plastics business in Albuquerque, he and Cecy moved to his boyhood hometown, La Porte, Indiana, where they eventual y took jobs at a junior high, Al en teaching science, Cecy teaching English. They were soon parents to a girl and a boy.

Al en hardly ever mentioned the war. His friends kept their questions to themselves, fearful of treading upon a painful place. Other than the scars on his forehead from the Green Hornet crash, only his habits spoke of what he’d been through. After having lived for weeks on raw albatross and tern, he never again ate poultry. He had a curious affinity for eating food directly out of cans, cold. And the onetime king hot dog of his squadron wouldn’t go near an airplane. As the jet age overtook America, he stayed in his car. Only many years later, when his daughter lost her husband in an auto accident, did he brave the air to go to her.

He never returned to Japan, and he seemed, outwardly, free of resentment. The closest thing to it was the flicker of irritation that people thought they saw in him when he was, almost invariably, treated as a trivial footnote in what was celebrated as Louie’s story. If he was rubbed wrong by it, he bore it graciously. In 1954, when the TV program This Is Your Life feted Louie and presented him with a gold watch, a movie camera, a Mercury station wagon, and a thousand dol ars, Al en traveled to California to join Louie’s family and friends on stage, wearing a neat bow tie and looking at the floor as he spoke.

When the group posed together, Al en slipped to the back.

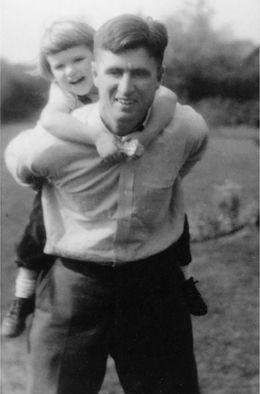

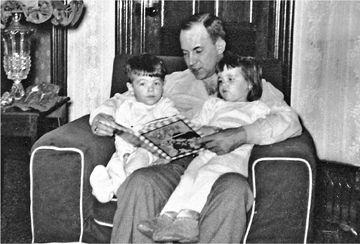

Al en Phil ips with his children, Chris and Karen, bedtime, 1952. Courtesy of Karen Loomis